U.S. Debt Ceiling Fight Threatens Bond-Yield Havoc

July 18, 2011Market Reacts to BoC Press Release and Latest CPI Data

July 25, 2011 Canadians are still enjoying the story of The Little Economy That Could. While the European and the U.S. economies struggle to reduce their crushing debt levels and Chinese inflation threatens to bring its economy to a rolling boil, we just keep chug-chugging along.

Canadians are still enjoying the story of The Little Economy That Could. While the European and the U.S. economies struggle to reduce their crushing debt levels and Chinese inflation threatens to bring its economy to a rolling boil, we just keep chug-chugging along.

But we are also balancing on a knife edge, waiting for the global economy to get back on its feet while we stand perched in this precarious but advantageous position, where strong domestic growth has bolstered our real estate markets and the uncertainty of the global recovery has kept our mortgage rates ultra low. Today’s post is my quarterly mortgage market update and in it I’ll describe how unfolding global events might impact our mortgage rates and, in keeping with tradition, I’ll offer a view on where fixed and variable-interest rates may be headed in future.

Let’s begin with our neighbours to the south who buy about 80% of our exports. After the U.S. credit bubble burst, there was but one cure: deleveraging. The only real choice left was whether to make the pain acute and severe, or chronic and dull; not surprisingly, political leaders decided to minimize today’s pain and postpone worrying about tomorrow’s pain until tomorrow.

Well, in the U.S., tomorrow is getting worse all the time. Two rounds of quantitative easing, massive federal budget deficits, and short-term rates at 0% for nearly three years failed to prevent anemic growth, coincided with a scary surge in long-term unemployment, and contributed no lasting momentum to the U.S. economy. At this point, most economists think that additional stimulus will probably do more harm than good, and it is becoming increasingly clear that only an emergency event will cause political leaders on both sides of the aisle to put aside their differences and make the difficult long-term structural changes that are required to get U.S. federal debt back under control.

A report in USA Today provides a powerful example of the unsustainability of the U.S.’s current financing requirements. It pegs the unfunded liabilities in the country’s Social Secur ity and Medicare programs at $59 trillion and says that if the U.S. federal government were required to record these liabilities at the time they are incurred, as private companies must do in accordance with modern U.S. accounting standards, then today’s gross federal debt would equal 500% of total GDP. To put that in perspective, Greece’s gross debt is currently at 155% of its GDP (but more on that later).

ity and Medicare programs at $59 trillion and says that if the U.S. federal government were required to record these liabilities at the time they are incurred, as private companies must do in accordance with modern U.S. accounting standards, then today’s gross federal debt would equal 500% of total GDP. To put that in perspective, Greece’s gross debt is currently at 155% of its GDP (but more on that later).

Something has to give. Stimulus programs are being withdrawn, every level of government is focusing on cutting costs, and because deleveraging requires substantial credit contraction, the private sector hasn’t had any help from the real estate sector, as it would during a more normal recovery phase.

So what does this all mean for Canadian mortgage borrowers? It’s clear that the U.S. economy can’t withstand the shock of higher interest rates any time soon, and when you combine that with the fact that deleveraging is deflationary, not inflationary, U.S. interest rates should stay low for an extended period (unless there is a global bond-market shock or the feds bump their head on the debt ceiling and the market loses faith in U.S. treasuries – both of which are possible, although not yet likely in the short and medium term).

Low U.S. interest rates will act as a drag on Canadian rates because our economies are highly integrated. It’s a circular two-step process: 1) Our higher relative interest rates attract more foreign investment, which drives the Loonie higher. 2) The lofty Loonie then makes our exports more expensive and reduces U.S. demand for them, causing our economy to slow. Wash, rinse, repeat. The wider the gap in interest rates, the greater the slowdown in U.S. demand for our exports, with one force providing a counter balance to the other over time. Today, the gap between U.S. and Canadian short-term interest rates is at 1%, and that’s near the upper limit of where the experts I read think we should be, so if it widens with additional Bank of Canada (BoC) increases, keep your eye on the Loonie.

While the lagging U.S. economy remains a concern for continued Canadian growth, China has been our ace in the hole; not so much for what it buys from us directly (unless you count Vancouver real estate) but because of what its voracious demand for raw materials has done to world commodity prices. While our economy is now more diversified now than ever, it is still heavily resource based and high commodity prices are generally good for business in the Great White North.

While the lagging U.S. economy remains a concern for continued Canadian growth, China has been our ace in the hole; not so much for what it buys from us directly (unless you count Vancouver real estate) but because of what its voracious demand for raw materials has done to world commodity prices. While our economy is now more diversified now than ever, it is still heavily resource based and high commodity prices are generally good for business in the Great White North.

But here again there is concern. China’s inflation is accelerating, posting year-over-year increases of 5.5% in May and then 6.4% in June, with food prices leading the charge. At the same time, wages aren’t keeping pace with rising costs, and it’s understandably hard for an export-based economy built on cheap labour to make the necessary adjustments. After three short-term rate increases so far this year with a fourth expected soon, how tight does China’s monetary policy have to get to bring inflation under control? This is an important question for Canadians because a significant reduction in Chinese demand would remove a key source of support for commodity-based economies like ours.

China may also be in the midst of a credit bubble. Its central government recently disclosed that local governments have racked up $1.6 trillion in debt and the country’s National Audit office was surprisingly candid when it acknowledged that “due to inadequate repayment ability, some local governments can only pay their debts by taking on still more debt”. We can guess how that story ends.

But of all the external threats to the Canadian economy, none is more immediate th an the risk of European sovereign-debt default. Greek government debt is running at a staggering 155% of GDP and is expected to grow to 170% by next year (no word on whether that includes unfunded liabilities), Ireland’s prospects for economic growth have been strangled by austerity measures, and Portugal is now expected to need a second bailout in short order.

an the risk of European sovereign-debt default. Greek government debt is running at a staggering 155% of GDP and is expected to grow to 170% by next year (no word on whether that includes unfunded liabilities), Ireland’s prospects for economic growth have been strangled by austerity measures, and Portugal is now expected to need a second bailout in short order.

Worse still, the contagion is no longer limited to the Eurozone’s peripheral economies. Italy and Spain have massive debt loads with stagnant or shrinking economies, and both are simply too big to rescue. The bond markets have taken notice and both countries must now borrow at the highest rates they’ve seen in a long time. Higher rates make rolling over debt more expensive, and this increases the risk of eventual default. Fear begets more fear – it’s a vicious cycle that is hard to reverse.

(As an aside, I agree with the experts who say that the Eurozone is failing because you can’t have a unified monetary policy without having more centralized fiscal policies and more coordinated political leadership. Without closer cooperation, this model will continue to require that responsible countries bail out their profligate counterparts. Left unchanged, I think this union is doomed to keep lurching from one disaster to another.)

If one or more Eurozone countries do eventually default, it could trigger a Lehman Brothers-style event that plunges the world into severe recession and it’s hard to predict exactly what effect this would have on Canada. Would our government bonds be viewed as a safe haven, thus driving down yields and reducing fixed-mortgage rates, or would investors demand higher yields on all sovereign debt because it is no longer viewed as a risk-free asset class? Let’s hope we don’t have to find out.

If one or more Eurozone countries do eventually default, it could trigger a Lehman Brothers-style event that plunges the world into severe recession and it’s hard to predict exactly what effect this would have on Canada. Would our government bonds be viewed as a safe haven, thus driving down yields and reducing fixed-mortgage rates, or would investors demand higher yields on all sovereign debt because it is no longer viewed as a risk-free asset class? Let’s hope we don’t have to find out.

Canada has enjoyed modest but consistent economic growth combined with relatively mild inflation. Our federal balance sheet stands among the strongest in the developed world, we have recovered all of the jobs lost during the last recession (although to be fair, we have replaced many higher-paying full-time jobs with lower-paying part-time jobs), and our real estate markets have weathered the downturn as well as any other country. So why are we all so nervous?

Well, the world outside our borders is certainly sapping our confidence and our recent GDP growth and buoyant real estate markets have been fueled by heavy doses of government stimulus and record levels of consumer debt. We haven’t yet proven that we can grow without more public and private borrowing, and it appears that we’re going to have to wait much longer than we had hoped for the global economy to right itself.

I think fixed rates…

aren’t going anywhere fast. Some folks seem to think that locking in a five-year fixed-rate below 4% is a no brainer but I disagree. You can certainly argue that when rates are this low they can’t go much lower, but that doesn’t mean they will immediately head higher either. We’re in the midst of a deleveraging cycle, and these tend to last for a long time (eight to ten years, historically). With most governments out of stimulus options, I think growth is  going to happen slowly, one small step at a time.

going to happen slowly, one small step at a time.

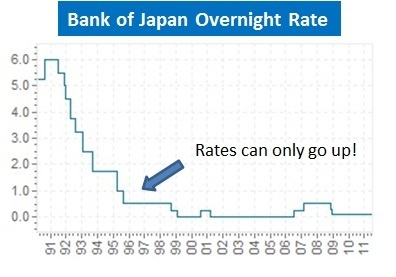

If you want a fixed rate because it will help you get a good night’s sleep or you happen to think we’re going to see significant inflation sooner rather than later, then locking in makes sense. But don’t do it because you buy the hype that “rates can only go up”.

I think variable rates…

still make sense. A five-year variable rate at 2.15% is still 1.5% cheaper than the equivalent fixed rate, and in today’s economy, that spread still seems like a chasm to me. Here are five reasons:

- As mentioned above, every time our rates rise and the gap between Canadian rates and U.S. rates widens, the Loonie soars higher. This increases the marginal impact of every incremental rate hike.

- The BoC raises rates to slow inflation, and with Canadian debt levels at record highs, the BoC shouldn’t have to increase rates by much to inflict the necessary pain to slow spending.

- There is still plenty of slack for our economy to absorb, and most importantly, the cost of labour is rising more slowly than the general rate of inflation. This matters because labour costs are normally the largest single contributor to broad-based inflation.

- The BoC’s latest growth forecast has our economy growing 2.8% in 2011, 2.6% in 2012 and 2.1% in 2013. These growth rates would not normally correspond with the kind of inflation that would lead to significantly higher rates.

- Historically, when the BoC starts increasing short-term rates, it has raised an average of 2% over a period of about 18 months. In today’s environment, where risk, uncertainty and volatility abound, I think the BoC will increase rates much more gradually, using a more cautious wait-and-see approach.

My best guess is that variable rates will still save you money over the next five years, but you’re going to need to have the stomach for some rate increases along the way, because at some point the ride is bound to get a little bumpy. (As always, banking today’s savings by setting your payment above the minimum will increase these odds.)

Wrap Up

Now would probably be a good time to remind readers that trying to decide between a fixed or variable-rate mortgage is a complex decision that incorporates many factors such as the size and security of your income, the overall strength of your personal balance sheet, and your psychological tolerance for interest-rate risk. Also, choosing a mortgage isn’t a one-size-fits-all proposition, so if you need advice, find a good mortgage planner who can offer lots of different options and who will walk you through the decision-making process.

While understanding how different facets of the global economy affect our economy will help inform your view of where rates are headed, in the end, we’re all just making our best guess. As Yogi Berra said, “predictions are difficult, especially about the future.” The most important advice I can give you is to make sure that the size and terms (fine print especially) of your mortgage don’t leave you standing on a knife edge; we’ll leave the balancing act to the agile Mr. Carney.