Variable-Rate Mortgages Still Look Better By Comparison

April 18, 2011S&P Lowers Outlook on U.S. Government Debt

April 25, 2011Mortgage rates and inflation go hand in hand.

Variable-mortgage rates are set using the Bank of Canada’s overnight rate, which it uses to control short-term inflation. If the Bank of Canada’s governors think we have too much short-term inflation, they raise the overnight rate to slow the economy; the cost of short-term borrowing increases, and variable-mortgage rates rise.

Fixed-mortgage rates are really a by-product of financial bets made about future inflation. If fixed-income investors think that inflation will rise in the future, they will demand a higher yield on longer-term bonds to preserve their real rate of return; this raises the cost of borrowing and results in higher rates for fixed-rate mortgage holders.

So if you want to know what will happen to interest rates in the future, all you really need to do is figure out how much inflation we’re going to have. Simple, right? Umm, not so much.  If you start researching this question, it won’t take long for you to realize there is a raging debate between those experts who believe inflation is about to take off, and those who believe it will remain benign for an extended period. In today’s post, my quarterly mortgage market update, I’ll outline the arguments on both sides of this debate before closing with my usual recommendations on both fixed and variable rates going forward.

If you start researching this question, it won’t take long for you to realize there is a raging debate between those experts who believe inflation is about to take off, and those who believe it will remain benign for an extended period. In today’s post, my quarterly mortgage market update, I’ll outline the arguments on both sides of this debate before closing with my usual recommendations on both fixed and variable rates going forward.

In its simplest form, inflation is usually defined as a general rise in the price of goods and services. While inflation can be limited to specific countries and regions, U.S. inflation spreads, at least to some extent, to just about every corner of the globe. This is because: a) The U.S. is the world’s largest economy, b) The U.S. dollar is the world’s reserve currency, c) Many countries peg their currencies to the U.S. dollar, and d) World prices for commodities like oil and gold are set in U.S. dollars (which means you must buy U.S. dollars to pay for these goods). Canada’s vulnerability to U.S. inflation runs much deeper because our two economies are closely interlinked (we are by far each other’s largest trading partner). So while our domestic data get most of the headlines in the inflation debate (the productivity index, capacity utilization rates, unemployment rates), I would argue that the elephant in the room is really the U.S. inflation question.

The view that Americans (and by association Canadians) are headed for significant inflation usually centres on their massive, and growing, levels of government and personal debt. A January, 2011 report from the U.S. Congressional Budget Office showed that combined personal and corporate tax revenues were $1.1 trillion, compared to the federal government’s current annual budget deficit of $1.3 trillion. So even if tax revenues were doubled, the feds would still be spending about $200 billion more than they take in. Worse still, these deficits are happening while hundreds of billions of dollars that are supposed to be put aside to fund the future cost of entitlement programs, like Medicare and Social Security, are being spent today instead of saved for later. So not even pilfering from the future is making a dent in the size of the U.S. federal government’s shortfall between spending and revenue.

At this point, you’re probably wondering how they can get away with this. Well, being the world’s reserve currency certainly helps, and over half the U.S.’s outstanding debt is owned by foreigners who haven’t yet lost their appetite for U.S. treasuries (with emphasis on the word “yet”). A recent Barron’s article put it well: “The demand for dollars from the rest of the world has been an inestimable benefit to the U.S. economy. It quite simply allows Americans to consume more than they produce and save less than they invest, in other words, to live beyond our means.”

At this point, you’re probably wondering how they can get away with this. Well, being the world’s reserve currency certainly helps, and over half the U.S.’s outstanding debt is owned by foreigners who haven’t yet lost their appetite for U.S. treasuries (with emphasis on the word “yet”). A recent Barron’s article put it well: “The demand for dollars from the rest of the world has been an inestimable benefit to the U.S. economy. It quite simply allows Americans to consume more than they produce and save less than they invest, in other words, to live beyond our means.”

Ben Bernanke’s quantitative easing (QE) programs have provided some much needed stimulus to the U.S. economy, but QE is really just money printing by another name, and Helicopter Ben’s money- printing presses are cranking out $2.3 million per minute ($3.3 billion/day). Those are a lot of extra dollars for the economy to absorb.

From a political standpoint, running deficits means that hard choices can be avoided by kicking the proverbial can a little farther down the road. Over time though, the cost of servicing this massive debt becomes unsustainable, even more so when investors lose their appetite for U.S. treasury bonds and the federal government must offer higher interest rates to continue funding their shortfall (Canada got there in the 1990s). When this point is reached, the only two choices are austerity measures or some form of default.

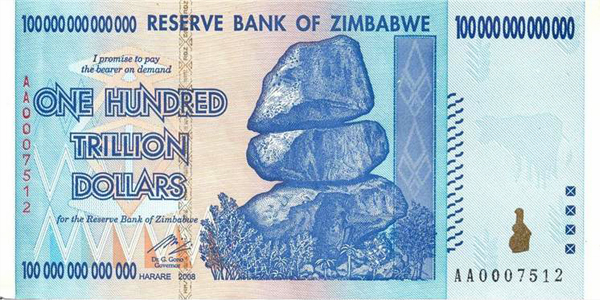

Austerity measures are painful, politically toxic, and long lasting, so defaulting one way or another becomes the more politically appealing choice (especially since, as we just mentioned, more than half of the U.S. debt is owned by foreigners who don’t vote in U.S. elections). When you get right down to it, a policy of aggressive inflation is really just a slow and gradual way to default over time, and from a political standpoint, inflating your way out of debt can be far more attractive than the alternatives: the real cost of debt is lowered, tax revenue is increased, and citizens ‘feel’ richer because they have more cash in their pockets (even though the real purchasing power of each dollar has been diminished).

The trouble with letting inflation take off is that it is very difficult to put the genie back in the bottle when you’ve had enough, and before you know it, you’re rolling a w heel barrow full of cash down to the corner to buy a litre of milk. Hyperbole aside, there are already signs that U.S. inflation has begun its upward march. Commodity prices (which again, are based in U.S. dollars) have shot up, and price increases are spreading to consumer staples. The Producer Price Index is now rising at an annualized rate of 20% and many believe that it’s only a matter of time before those price increases are passed on to consumers.

heel barrow full of cash down to the corner to buy a litre of milk. Hyperbole aside, there are already signs that U.S. inflation has begun its upward march. Commodity prices (which again, are based in U.S. dollars) have shot up, and price increases are spreading to consumer staples. The Producer Price Index is now rising at an annualized rate of 20% and many believe that it’s only a matter of time before those price increases are passed on to consumers.

Foreign investors are also worried about U.S. inflation and as they try to hedge their bets by offloading their U.S. dollars, the currency’s purchasing power is eroded further. (Some have speculated that China’s purchasing binge of companies, commodities and just about everything that isn’t nailed down is, in part, a more clever way of unloading U.S. dollar reserves than simply flooding them into the currency markets and destroying their value in the process.) This is significant to the inflation debate because a currency with less purchasing power has the same effect on its domestic economy as rising prices – they are fruit from the same tree. Signs of waning confidence in the Greenback abound, with Standard & Poor’s downward revision of its long-term rating outlook on U.S. government debt yesterday serving as the best and most recent indication.

On the other hand…

It’s true that raw-material prices are rising, but those who think that inflation will remain benign for the foreseeable future argue that commodity price increases will merely result in less consumer spending on discretionary items. In other words, they believe that higher food and energy prices are more likely to be deflationary. David Rosenberg argues that every $10 increase in the price of oil shaves .25% off GDP growth and he also points out that since two-thirds of U.S. consumer spending is on services, the impact of higher raw-materials prices will have only a limited impact on the broader economy.

While it’s true the federal reserve’s printing presses have been busy increasing the money supply, banks are lending less and consumers are borrowing less, so as Bill Bonner (President of Agora Inc.) put it, “the explosion of money printing is being contained by the bomb squad of deleveraging”. More money doesn’t create inflation if it’s sitting on bank balance sheets instead of circulating through the economy – and when the stimulus effects of QE are no longer propping up the economy, many worry that economic growth will slow considerably (the latest round of QE is expected to be wound up in June, 2011).

While it’s true the federal reserve’s printing presses have been busy increasing the money supply, banks are lending less and consumers are borrowing less, so as Bill Bonner (President of Agora Inc.) put it, “the explosion of money printing is being contained by the bomb squad of deleveraging”. More money doesn’t create inflation if it’s sitting on bank balance sheets instead of circulating through the economy – and when the stimulus effects of QE are no longer propping up the economy, many worry that economic growth will slow considerably (the latest round of QE is expected to be wound up in June, 2011).

Let’s not be so quick to write off attempts at austerity measures either. U.S. state and local governments are close to bankruptcy and are proposing substantial cuts to the health benefits and pensions of public sector workers. Infrastructure projects are being delayed or shuttered, and all of this will be negative for economic growth.

One of the most significant causes of past inflation has been higher labour costs, but with both Canadian and U.S. unemployment levels well above historical averages, labour costs are stable and likely to stay that way for some time.

While it’s true that foreign governments and investors are concerned about current U.S. deficit and debt levels, the U.S. dollar is still seen by many as a safe-haven currency (the most recent examples are that the Greenback rose after Japan’s earthquake/tsunami and after Portugal asked the EU for a bailout). The U.S. dollar has been the world’s reserve currency since the end of WWII and there is really no viable alternative at this point, unless you want to argue that we should all go back to the gold standard or accept China’s proposal for a new world currency (which sounds good until you read a little more about it).

Lastly, while just about everyone agrees that the U.S. federal government’s current spending levels are unsustainable, don’t forget that U.S. citizens pay very low personal tax and consumption rates, so there is room to increase tax revenues alongside spending cuts.

As for where I fit in this debate and more importantly, what it may mean for Canadian mortgage rates:

I think Fixed Rates…

are expensive at current levels. Lenders understand that inflation is a friend to fixed-rate mortgage borrowers because it causes their earnings to rise while their interest cost stays the same, and they account for this risk in their pricing. In times of market volatility (like now), where the risk of higher inflation is difficult to quantify, lenders will instinctively err on the side of caution. That means that in today’s environment, the cost of fixed-rate security increases.

stays the same, and they account for this risk in their pricing. In times of market volatility (like now), where the risk of higher inflation is difficult to quantify, lenders will instinctively err on the side of caution. That means that in today’s environment, the cost of fixed-rate security increases.

Of course, if you’re convinced that inflation is around the next corner, fixed rates are a good bet. But most fixed-rate borrowers choose five-year terms and if you buy the argument that inflation will remain benign for the short and medium term, you’ll be paying a significant premium today for a hedge against inflation that may still be years off. That’s the trade-off.

For my money, today’s fixed rates seem expensive and because I think sustained inflation is still a ways off, my own mortgage rate remains variable. But there are too many factors in play to know for sure, so of course, each borrower must decide for him or herself.

I think Variable Rates…

will stay low for longer than most forecasters are predicting. While Canada’s rate of economic growth is still encouraging, I agree with the latest Bank of Canada report that says our momentum will be tested by factors like: the appreciating dollar, higher energy and food prices, weakness in our dominant export market (the U.S.), the potential for more hiccups in the global economic recovery (i.e. sovereign debt defaults) and continued supply-chain disruptions in Japan. Of these, our expensive dollar will act as the strongest deterrent to rate hikes because increased rates will attract more foreign investment which will drive the Loonie higher still. For this reason, I contend that there is a low probability that the Bank of Canada will significantly increase the overnight rate for as long as the Loonie is so strong against the Greenback.

While a higher dollar slows our economy by making our exports more expensive, it also lowers the cost of our imports, which helps keep inflation in check. We see evidence of this in the data, and even though core inflation jumped to 1.7% yesterday, the Bank of Canada is already on record as saying that it expects short-term spikes in inflation to be temporary. Also, keep in mind that when inflation does start to pick up, with Canadian consumer debts at record levels, short-term rates shouldn’t have to be increased by much to cause enough pain to slow the rate of inflation if and when it becomes a concern.

Wrap-up

With the spread between five-year fixed and five-year variable rates at more than 2% (2.15% vs. 4.19%), variable rates look like a bargain to me. It’ll take a little more courage to stay in variable now that fixed rates have started to rise (because the cost of your parachute is going up!), but I still think the reward justifies the risk for most borrowers. Of course, the best way for you to tilt the odds in your favour,  if you’re a variable-rate mortgage holder, is to set your mortgage payment at the higher fixed rate and use today’s savings to pay off your principal much more quickly. Think of it as saving for an inflationary day.

if you’re a variable-rate mortgage holder, is to set your mortgage payment at the higher fixed rate and use today’s savings to pay off your principal much more quickly. Think of it as saving for an inflationary day.

1 Comment

Many good points Dave. Variable rate mortgages are always a better choice from a long term interest cost point of view, especially when that cost is not tax deductible. However, most borrowers are more concerned wit their cash flow and their family budgets. My view is if the consumer has the risk tolerance, financial strength and income to weather increase in interest rates, he or she should take advantage of the low variable rates, but find a lender who will allow fixing payments. Fix the payments at a higher level than the minimum the lender allows. That creates predictable cash outlay and extra cushion in the event of rate increases. At the same time, that will help pay off the non-tax-deductible debt that much sooner.