Why Are Canadian Fixed Mortgage Rates Rising Again?

October 21, 2019The Bank of Canada Didn’t Cut Last Week, But It Likely Will Soon

November 4, 2019 Fixed mortgage rates continued their slow climb last week, but it was an otherwise uneventful week for mortgage-rate news as all eyes turned towards the Bank of Canada (BoC) meeting this Wednesday.

Fixed mortgage rates continued their slow climb last week, but it was an otherwise uneventful week for mortgage-rate news as all eyes turned towards the Bank of Canada (BoC) meeting this Wednesday.

With that in mind, in today’s post I had initially planned to revisit the age-old fixed-versus-variable rate question, which is always a popular topic. But in the current environment where our bond-yield curve remains inverted and fixed rates are lower than variable rates, that question seems less compelling. Simply put, when borrowers aren’t receiving a discount to take on variable-rate risk, they just aren’t inclined to do it.

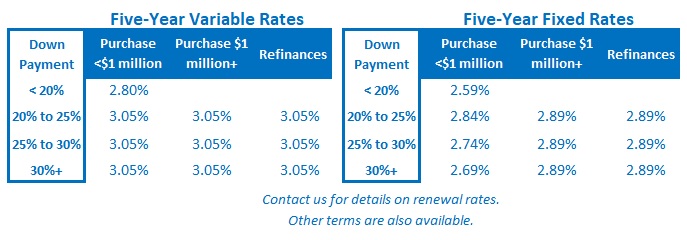

Today the vast majority of buyers are opting for a five-year fixed rate. In addition to having rates that are lower than equivalent variable rates, they are now also cheaper than almost all other fixed-rate terms.

While this current backdrop has simplified the range of options for borrowers, it has not levelled the playing field. Five-year fixed-rate mortgages are not created equal. To wit, in the current environment, mortgages that offer maximum flexibility have proven far more economical than alternatives that may be lower priced but are less flexible.

Here is an example that illustrates why flexibility is so valuable:

Let’s assume that it’s November 2018 and you have just purchased your first property for $375,000.

You have managed to save $75,000 for your down payment and your first call is to a mortgage broker who offers you a rate of 3.29% (and yes, rates were that high only twelve months ago).

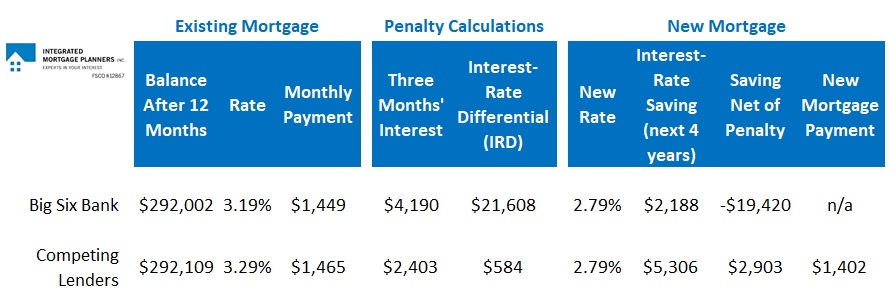

Before signing on the dotted line, you call the Big Six bank you have been with since you were a kid, quote the rate your broker offered you, and ask if they can beat it. Your bank offers you 3.19%, and you calculate that on a $300,000 mortgage amortized over 25 years, that 0.10% discount will save you $1,420 in interest over your five-year term. You sign on the dotted line.

Fast forward to today.

You read that mortgage rates have fallen, and a quick search confirms that if you bought the same property today, only twelve months later, you would be able to borrow the same $300,000 at a five-year fixed rate of 2.79%. Some quick calculations show that this rate would save you $4,442 over the remaining four years of your current term (while also adding another year at the lower rate on the back end since you would be locking in a new five-year term).

You call your local banker and ask if you can refinance your existing mortgage to take advantage of the drop in rates. They explain that you will need to pay a penalty to break your current mortgage, which the bank calculates by taking the greater of three months’ interest (at the five-year posted rate the bank offered when you got your mortgage), or the interest-rate differential (IRD), which it calculates using the methods that I outline in detail in this post.

The bank’s penalty of three months’ interest works out to $4,190 but the IRD penalty works out to $21,608. Given that the bank uses the greater of these two numbers, the penalty that you would have to pay is $21,608. Suddenly that interest-rate saving of $4,442 doesn’t seem so exciting.

That prohibitive penalty leaves you no choice but to wait out the next four years, to forego the $4,190 saving you were hoping for, and to hope that rates are still lower when you renew your mortgage at the end of your five-year term.

Now let’s go back to November 2018, but this time we’ll assume that you had chosen the competing lender instead.

The slightly higher rate of 3.29% versus 3.19% would have cost you $295 more in interest over the first year, but the cost to break this mortgage would be a fraction of what the major bank quoted.

The competing lender uses similar formulae to calculate your penalty, but with some very important differences. Their three-month interest penalty is calculated using your contract rate, not the inflated posted rate (which lowers it from $4,190 to $2,403), and their IRD penalty is calculated using the Standard Method that I outline in my post on the topic (which lowers it from $21,608 to $584).

In this case, the competing lender’s penalty would only cost you $2,403, while securing a new rate at 2.79% will reduce your interest cost by $5,306 over the next four years, for a net saving of $2,903.

(Note: the saving available differs in the two examples above because I have assumed that in both cases the full penalty is rolled into the new mortgage before the net saving is calculated.)

The chart below captures the key data from both examples:

In summary, if you were looking for a mortgage twelve months ago, the initial difference in the rates offered amounts to just a rounding error when compared to the difference in the long-run saving that you can unlock by accessing the competing lender’s much more reasonable penalty charge.

The scenario above is a real-world example.

If you took out a mortgage twelve months ago from a lender that charges reasonable penalties, there is a strong likelihood that breaking it now and refinancing at a lower rate could save you a significant amount of money. (And of course, many borrowers who never expected to break their mortgages also find they have to do so because their personal circumstances change before their five-year term expires.)

The next obvious question is how likely this is to matter to the average borrower in future. Can rates continue to fall as they have over the past twelve months?

There are certainly no guarantees. To quote from Yogi Berra, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.”

That said, here are some examples of why five-year fixed-rate borrowers may still want to prioritize flexibility in our current environment:

- Roughly one-quarter of the global bond market now trades at a negative yield. By comparison, the Government of Canada (GoC) bond yield, which our five-year fixed rates are priced on, closed last Friday at 1.57% – high by world standards.

- The U.S Federal Reserve is expected to cut its policy rate once again when it meets this week. The more the Fed cuts, the more pressure there is on the BoC to follow suit.

- The IMF now predicts that global GDP growth will slow to 3% in 2019, marking its lowest level since the financial crisis in 2008. That portends more slowing in the developed world’s economies, and if they slide into outright recession, mortgage rates are very likely to fall further.

- Denmark recently introduced the first negative interest-rate mortgage (and no, the Danes don’t lend in Canada)!

- Three years ago, I was booking five-year fixed-rate mortgages at 2.09%. (In other words, we’ve been a lot lower than today’s levels in our recent past.)

Last but not least, in the example above, I assumed that the Big Six bank beat the competing lender’s rate by 0.10% to show that even in that case, the much lower penalty is worth far more to you than the slightly lower interest rate. In reality however, non-bank lender rates are very competitive, and in many cases you secure the most flexible penalty terms with a rate that is equal to or lower than what your bank is offering. There is a big and diverse market out there. The key is knowing where to look.

The Bottom Line: Five-year fixed rates continued to edge higher last week, and variable mortgage rates were unchanged. The BoC is not expected to move its policy rate when it meets this week, but a change in its descriptive language could impact GoC bond yields and the fixed mortgage rates that are priced on them. I’ll offer my take on what the BoC says in next week’s post.

The Bottom Line: Five-year fixed rates continued to edge higher last week, and variable mortgage rates were unchanged. The BoC is not expected to move its policy rate when it meets this week, but a change in its descriptive language could impact GoC bond yields and the fixed mortgage rates that are priced on them. I’ll offer my take on what the BoC says in next week’s post.