The Bank of Canada Blinks

April 26, 2021Disappointing Employment Data Portend Less Inflation (and Lower Mortgage Rates)

May 10, 2021 In its most recent policy statement, the Bank of Canada (BoC) moved up the timing of its next policy-rate increase to “sometime in the second half of 2022”, and the consensus wasted no time in warning variable-rate mortgage borrowers to lock in.

In its most recent policy statement, the Bank of Canada (BoC) moved up the timing of its next policy-rate increase to “sometime in the second half of 2022”, and the consensus wasted no time in warning variable-rate mortgage borrowers to lock in.

In last week’s post, I offered a different take.

I argued that our rates will likely stay lower for longer, and that the BoC’s statement was primarily designed to help cool our red-hot housing markets. I noted that the Bank left itself plenty of wiggle room by repeatedly emphasizing uncertainty throughout its forecast and by making clear that its ultimate timing would be outcome based, not calendar based. I also predicted that the BoC would not raise ahead of the US Federal Reserve and reminded readers that the Fed was not projecting its next rate hike until 2024.

In this week’s post, I’ll offer more detail on why I think the BoC will lag the Fed, and then provide an update on what the Fed said last Wednesday at its latest policy-rate meeting.

First, a quick reminder.

The BoC’s more optimistic forecast is underpinned by the belief that “strong growth in foreign demand” will lead to a “robust recovery in exports and business investment”. In that ideal scenario, those sectors take the baton from our current source of momentum, which remains, undeniably, our housing sector.

The part of the Bank’s most recent forecast that I have the hardest time reconciling is the confluence of its next rate hike and the dawn of our long-awaited export revival. If the BoC raises before the Fed, the Loonie will continue to appreciate against the Greenback. The more intense that already powerful economic headwind becomes, the greater the risk that it will kill off any export-led recovery.

We don’t have to look back very far to see the damage that a lofty Loonie can inflict on our export sector.

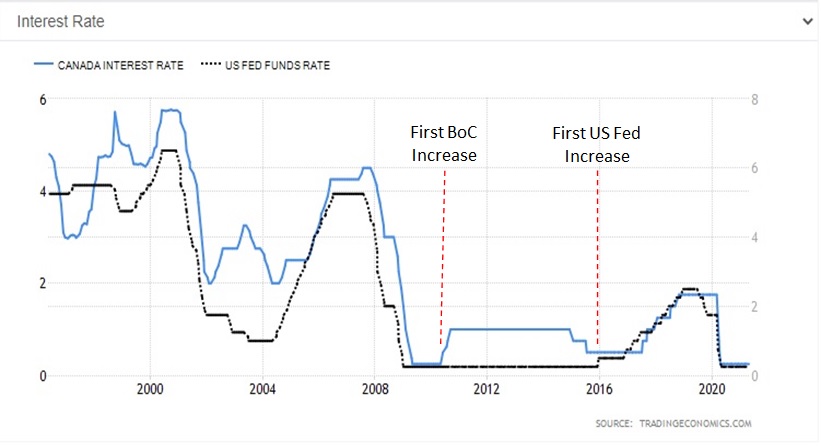

When the Great Recession hit back in 2008, both the BoC and the Fed slashed their policy rates to 0% in response. The Canadian economy rebounded relatively quickly and that prompted the BoC to start raising in early 2010. It hiked four times that year, and by September its policy rate was up to 1.00%. The US economy was recovering more slowly over that period, and so the Fed kept its policy rate nailed to the floor until early 2016 (see chart).

The Loonie had already been rising through 2009, but took off after the BoC began raising its policy rate, and it eventually peaked at $1.05 USD in July 2011. It remained above its long-term average until 2015, when oil prices crashed (and the BoC enacted two 0.25% rate cuts).

The Loonie had already been rising through 2009, but took off after the BoC began raising its policy rate, and it eventually peaked at $1.05 USD in July 2011. It remained above its long-term average until 2015, when oil prices crashed (and the BoC enacted two 0.25% rate cuts).

The chart below tracks our export performance over that same period, and the dotted line shows that it took about six years for our total export sales to recover to their pre-Great Recession levels. (To be clear, the lofty Loonie wasn’t the only reason that recovery took so long, but it was a powerful headwind at an inopportune time.) Fast forward to today.

Fast forward to today.

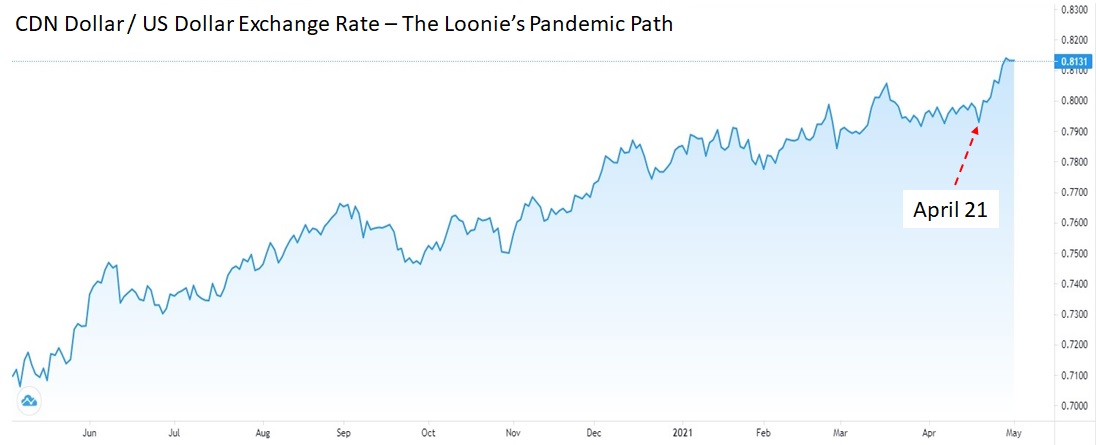

In its most recent Monetary Policy Report, the BoC noted that the Loonie had risen by about one cent against the Greenback since the start of the pandemic. That may not sound like much, until you consider that almost all other major currencies have weakened against the Greenback over that same period.

The Loonie’s rise over the past year has been a result of many factors such as a strong demand for the commodities we produce, but it has spiked by an additional two cents since the BoC announced its expected rate-hike timetable on April 21 (see chart), and it is reasonable to attribute that run-up

to the Bank’s hawkish turn.

While the BoC can certainly raise ahead of the Fed, if past is prologue, it seems unlikely that it will have the luxury of doing so without seriously damaging the sustainable export-led recovery that it says must underpin any raises.

Now that I’ve explained why I don’t think the BoC will raise its policy rate before the Fed, let’s turn our attention to what the Fed said at its policy meeting last Wednesday.

In the lead-up, the consensus predicted that the Fed would hint at plans to taper its quantitative easing (QE) programs and also likely move up its rate-hike timetable.

It did neither.

Instead, the Fed again doubled down on its lower-for-longer approach and pushed back against the narrative that it is close to any monetary-policy tightening.

Here are the highlights from the Fed’s latest statement and from US Fed Chair Powell’s related commentary:

- The Fed reiterated that it expects the current run-up in US inflation to prove transitory. It attributed the rise to the normalization of prices that collapsed at the start of the pandemic and to supply shortages caused by temporary bottlenecks.

- The Fed observed that “while the recovery has progressed more quickly than generally expected, it remains uneven and far from complete.” Its central message was that it will leave its ultra-accommodative policies in place until it sees “substantial further progress” toward its dual mandate of maintaining price stability and achieving maximum employment. Powell added that the Fed is still “a long way” from its goals.

- The US economy has recovered approximately 60% of the jobs it lost during the pandemic, which works out to about 8.5 million jobs. Powell emphasized that the Fed will not raise its policy rate until the employment recovery is “complete”. He also predicted that the recovery may be prolonged because not all of the old jobs will come back and said that companies have told the Fed they are focusing on “better technology and perhaps fewer people”. (The BoC has noted the same trend in Canada, which it refers to as “digitization”.)

- Powell deemed it “unlikely” that inflation will move up “in a persistent way … while there was still significant slack in the labor market”. Once that slack is absorbed, the Fed plans to “maintain an accommodative stance” until it averages 2% over time. Given that it has run “persistently below” that level for some time now, the Fed has plenty of room to let inflation run hot over the short and medium term.

- Powell said that he expects that the Fed will begin to taper its QE programs “well before the time we would consider raising interest rates”. He added that he would let the public know “well in advance of any actual decision to taper our asset purchases”. In other words, the Fed will first talk about tapering, then actually taper, and only then consider raising its policy rate.

The market consensus expected the Fed to move up its tightening timetable, but the Fed pushed back against that notion, and its average “dot plot forecast” continues to project that its next rate hike won’t come until 2024. The Bottom Line: The BoC is now forecasting that it will raise its policy rate sometime in the second half of next year, alongside an export-led recovery.

The Bottom Line: The BoC is now forecasting that it will raise its policy rate sometime in the second half of next year, alongside an export-led recovery.

For the reasons outlined above, raising so far ahead of the Fed would risk killing our golden goose just as it is starting to lay eggs, and I don’t see that happening because the lessons learned from 2010 should still be fresh in the Bank’s mind.

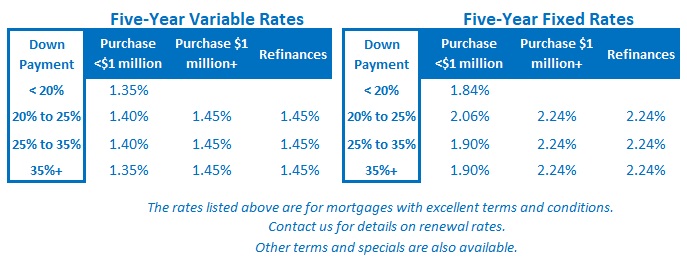

Fixed and variable rates held steady last week.