Why Did Financial Markets React as if the U.S. Federal Reserve Raised Last Week?

August 6, 2019Denmark Introduces the First Mortgage with a Negative Interest Rate

August 19, 2019 The Bank of Canada (BoC) has made it clear that it will not hurry to match rate cuts by the U.S. Federal Reserve.

The Bank of Canada (BoC) has made it clear that it will not hurry to match rate cuts by the U.S. Federal Reserve.

At its last meeting, in July, the Bank assessed that the Canadian and U.S. economic trajectories were converging. Canadian economic momentum was recovering after a slump, and U.S. economic momentum was slowing after a period of above-potential growth. Against that backdrop, the BoC argued, divergent monetary-policy actions were justified.

It is also true that the Fed raised its policy rate by a quarter point nine times during its most recent tightening cycle while the BoC hiked only five times. Even after the Fed’s most recent cut, its policy rate still operates in a range that is 0.25% to 0.50% higher than the BoC’s policy rate.

In that context, I agree that the BoC shouldn’t run out to match the Fed’s next move as long as the Loonie isn’t soaring against the Greenback (which right now, it isn’t). But the Bank has other reasons to cut its policy rate at its next meeting, regardless of what the Fed is doing.

This may sound counter-intuitive based on our recent economic data.

The Canadian economy has been putting up surprisingly strong numbers of late. Our month-over-month GDP growth has beaten consensus forecasts three months in a row, with broad-based gains spread across both our service and goods-producing sectors. We saw our best month for employment growth ever in April (107,000 new jobs), and while we learned last week that our economy shed 24,000 jobs in July, our average wage still rose by 4.5% on a year-over-year basis, marking a new cycle high.

Nonetheless, monetary policy changes take time to work their way through our economy, and that means the Bank must look ahead, where there are too many storm clouds on the horizon to ignore.

Here are some of the growing headwinds the BoC must account for at its next meeting on October 30:

- The U.S./China trade war shows no signs of abating and now appears likely to get worse before it gets better. The longer this fight lasts, the more entrenched its negative impacts will become.

- The global economy is slowing sharply, and our economic momentum closely tracks global economic momentum. The IMF just slashed its 2019 estimate for global GDP growth from 3.7% to 3.3%, which The Economist recently noted will mark its lowest level since 2009.

- The rest of the world is dropping rates. Sixteen of the world’s central banks have cut their policy rates thus far in 2019, and more than $14 trillion worth of global bonds now trade at a negative yield, and that’s up about another trillion in the last two weeks alone. Government of Canada bond yields have also plummeted of late, in a clear sign that the BoC and the bond market don’t see eye to eye. (For those keeping score at home, the bond markets have a much better forecasting record than any central bank.)

- Much has been made of our impressive headline employment growth this year, but over that period, employment grew at twice the rate of our overall economy, and that’s an unsustainable trend. It may not even be a healthy one. There is speculation that companies are choosing to add labour rather than to invest in machinery and equipment because labour is more expendable if hard times hit. In other words, our recent employment surge could well be a sign of uncertainty, not rising confidence. Furthermore, when employment grows faster than economic output that inevitably means that productivity and efficiency are declining, something that is never good for any economy.

While the points listed above should be enough to give the BoC pause, its primary worry is of its own making.

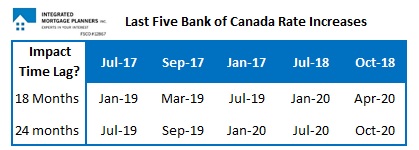

Remember the five BoC rate hikes that started in July 2017 and ended in October 2018? Remember the BoC’s estimate that it can take between 18 and 24 months for the full impact of each rate hike to work its way into the economy?

The third of those five rate hikes passed the 18-month mark last month (see chart), and that means we are now just about halfway through the total time it will take for the full impact of the BoC’s last tightening cycle to be realized. All else being equal, if the Bank leaves its policy rate unchanged, our economy will be undergoing monetary-policy tightening well into next year. Simply put, I think that the BoC overtightened during its recent rate-hiking cycle and that it should cut its policy rate at its next meeting to help lessen that cycle’s remaining unrealized impact.

Simply put, I think that the BoC overtightened during its recent rate-hiking cycle and that it should cut its policy rate at its next meeting to help lessen that cycle’s remaining unrealized impact.

This will be a tough call for the Bank, and one it wouldn’t even consider if it was worried about inflationary pressures. The BoC has repeatedly said that it will maintain price stability even if doing so produces negative side effects elsewhere in our economy. But in its latest Monetary Policy Report, the Bank forecast that inflation would drop to 1.6% in the third quarter of this year and not rise to 2% until the end of 2020, so it doesn’t appear to be too worried about inflation at the moment.

In a world where negative bond yields abound, policy makers may soon long for the day when inflation was their biggest concern.

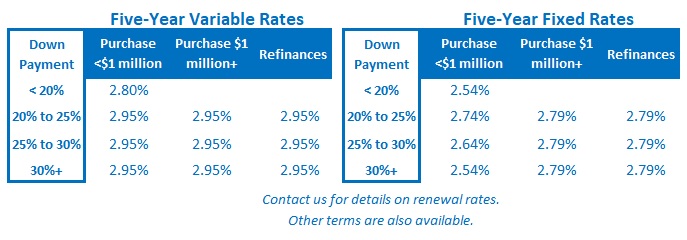

The Bottom Line: While most market watchers are focused on whether the Fed’s recent cut will compel the BoC to drop its policy rate, the Bank has its own domestic and more pressing reasons to cut at its next meeting. In the meantime, GoC bond yields continue to fall and fixed mortgage rates along with them.

The Bottom Line: While most market watchers are focused on whether the Fed’s recent cut will compel the BoC to drop its policy rate, the Bank has its own domestic and more pressing reasons to cut at its next meeting. In the meantime, GoC bond yields continue to fall and fixed mortgage rates along with them.

(For any who are interested, here is a link to my BNN Bloomberg interview last week where we talk about how the stress test is impacting non-prime lenders and why fixed mortgage rates are still lower than variable mortgage rates in the current environment.)