How the Latest Employment Data Will Impact Our Mortgage Rates

August 8, 2022The Bank of Canada’s Rate-Hike Impacts Are Intensifying

September 6, 2022Our bond markets and our central banks are not on the same page right now.

Both the US Federal Reserve (the Fed) and the Bank of Canada (BoC) are adamant that they will continue raising their policy rates until inflation and inflation expectations are brought to heel, and they have recently hinted that this will require more hikes than the market is currently pricing in.

Our central bankers concede that this will create economic pain, but they believe that pain will pale in comparison to the pain that will occur if inflation is left unchecked – and they continue to predict that they can pull off a soft-landing for our economies while all of this transpires.

For their part, bond-market investors expect that fewer additional rate hikes will be required to cool the over-heated sectors of our economies now that inflation appears to have peaked and because there are already signs of material slowing. The US and Canadian bond futures markets are currently pricing in a recession and associated rate cuts by both the Fed and the BoC in 2023.

I think both will be proven half right.

Before I explain why I write that, let’s take a brief look at the current inflation backdrop.

When the pandemic first hit, supply shortages were largely responsible for the first round of price rises. Massive amounts of stimulus caused demand to surge while bottlenecks constrained supply, and goods prices rose in response. Then food and energy prices spiked as our economies began to reopen, and even more dramatically, in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Fast forward to today.

Shipping costs have fallen sharply of late and are now near their pre-pandemic levels – an indication that supply bottlenecks have eased considerably, as have the prices of many food staples such as wheat, corn, palm oil and rice. Energy prices have also started to drop. Interestingly, the price spikes that led to our initial inflation surge are now, in fact, proving to be transitory, as our central bankers originally predicted (because transitory means “non-permanent”, and not, as many assumed, short lived).

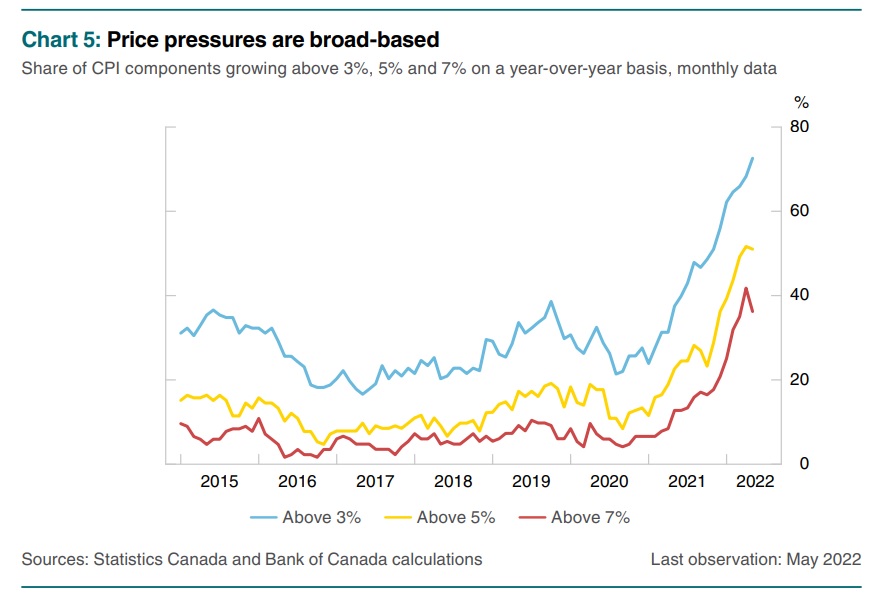

While the initial causes of our rise in inflation have begun to fade, other derivative types of inflation have now taken root, and price pressures have broadened as a result (see chart).

While the initial causes of our rise in inflation have begun to fade, other derivative types of inflation have now taken root, and price pressures have broadened as a result (see chart).

For example, although many companies have raised their prices to protect their existing margins in the face of rising costs, many others did so either in anticipation of higher costs to come, or because all the inflation talk gave them cover to pad their margins. (This recent Bloomberg article notes that US profit margins are now the widest they have been since 1950.)

At the same time, although wages were slow to respond to higher prices initially, they have risen steadily of late. Average hourly wages rose by more than 5% in July (year-over-year) in both Canada and the US, and we currently have a record number of unfilled job openings on both sides of the 49th parallel. Labour costs pervade every corner of an economy, and current labour-supply shortages make it unlikely that they will cool on their own. The increasing risk that rising labour costs will become entrenched adds to the urgency of the current situation and helps explain why our central bankers have adopted a better-safe-than-sorry approach to monetary-policy tightening over the near term.

Tighter monetary policies, which are being administered using a combination of policy-rate rises and quantitative tightening (QT), will help cool demand. That should, in turn, help reduce the current labour gap and put pressure on those fatter profit margins – but only after we endure the concomitant economic pain.

On that note, my expectations for the BoC’s rate-hike trajectory have changed recently.

I used to think that the scope of the BoC’s rate hikes wouldn’t end up matching its rhetoric – because our record-high household debt levels would magnify the impact of each BoC hike and because rate hikes take about two years to exert their full economic bite. I thought those factors would cause our momentum to slow sharply and the BoC to err on the side of caution. (After all, it wasn’t too long ago that the Bank’s biggest fear was staving off a repeat of the Great Depression.) But at the same time, I expected inflation to fall sharply when supply bottlenecks eased, and distortions tied to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine became less pronounced.

While those developments are now evident, price pressure persists.

In retrospect, what I didn’t fully appreciate was the scope of additional price rises occurring underneath the most prominent food and energy spikes that were garnering all the attention. It is that broadening out of price pressures that is now the dominant inflation threat, and I believe that quelling it will require more near-term tightening than the bond market currently expects and will need a longer delay before rate cuts are back on the table.

If we’re going to see a tougher monetary-policy stance by the BoC and the Fed over the near term and if it will take longer than previously expected for inflationary pressures to ease, then the odds that our economies will experience hard landings are greater now. That is especially true in Canada, because our households are much more highly levered and our economy is far more dependent on the interest-rate-sensitive real-estate sector for its momentum.

In summary, I think the hawkish rhetoric of the BoC and the Fed, which implies that there will be more near-term rate hikes than the market is pricing in and that rates will stay higher for longer, will prove prescient. On the other hand, I think their soft-landing forecasts are pure fantasy.

Conversely, I think the US and Canadian bond markets are underestimating how many rate hikes are yet to come, but I concur with the growing consensus view that a recession in both countries is increasingly likely (and may not be that far off).

Now let’s tie all this back to today’s mortgage options.

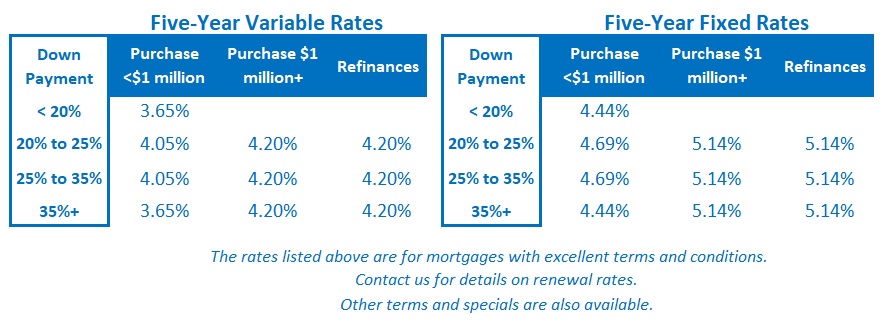

If you are currently in the market for a mortgage, I still believe that five-year variable rates will prove cheaper than five-year fixed rates over their entire term – maybe not over the first year or two, but in totality.

That said, if you value the stability of a fixed rate in these uncertain times (and there is certainly wisdom in that approach), I recommend looking at shorter term two- or three-year fixed rates. They will give you rate certainty over the near term when rates are most likely to rise and will also allow you to reset your rate at the end of that shorter term, around the time when we can reasonably expect the inflationary impacts of the pandemic and Putin’s war to be in the rear-view mirror.

If you currently have a variable-rate mortgage and are thinking of locking in, that decision depends on several factors, such as your existing discount off prime and the time remaining on your mortgage. For example, if you have a variable rate at prime minus 1% today (which works out to 3.7%) and you are offered a five-year fixed rate of 5%+ to convert, I suggest that you stay the course. But that recommendation might change if your discount off prime is smaller and/or you’ve got less time remaining on your existing term. In such cases there is now a good argument to be made for converting to a shorter-term fixed rate to ride out whatever comes next. The Bottom Line: The Government of Canada bond yields, which serve as baselines for our fixed mortgage rates, continued to rise last week. If that trend continues for much longer, lenders will probably start to raise their fixed rates in response.

The Bottom Line: The Government of Canada bond yields, which serve as baselines for our fixed mortgage rates, continued to rise last week. If that trend continues for much longer, lenders will probably start to raise their fixed rates in response.

Variable-mortgage-rate discounts held steady last week, and I don’t expect them to change in the lead up to the BoC’s next meeting on September 7 (when the Bank will hike again and, for the reasons outlined above, will also likely sound more hawkish than many currently expect).