What Will September’s Accelerating Wage Growth Mean for Canadian Mortgage Rates?

October 10, 2017New Mortgage Rules Announced: The Good, The Bad and The Ugly

October 23, 2017 Economic growth has been hard to come by since the start of the Great Recession.

Economic growth has been hard to come by since the start of the Great Recession.

Today, if you offered central bankers from the world’s developed economies a 2% annual GDP growth rate, most of them would take it and run. Even China, whose GDP grew by an average of almost 10% over the thirty-year period from 1980 to 2010, saw its annual GDP growth rate slow to 6.7% in 2016, marking a 26-year low.

When Canadian GDP growth came it at 4.5% in the second quarter of this year, some market watchers speculated that this accelerating growth would fuel higher inflation, and that led them to forecast that the Bank of Canada (BoC) would hike rates multiple times over the next twelve months.

I have offered a different view in recent posts, making the case that our rates are likely to stay lower for longer, and I highlighted the surging Loonie as one of the key factors that will contribute to that outcome.

My thinking was that while a relatively weak Loonie provided our economy with a tailwind in Q2, its surge after the BoC’s two policy-rate rises this summer has since converted that tailwind into a headwind.

It was only natural to conclude that the soaring Loonie would crimp demand for our exports, and our most recent export data have confirmed that to be the case (exports having fallen more than 10% from their peak in May). But waning export demand isn’t even the most significant factor that will slow our economic momentum over the next twelve months.

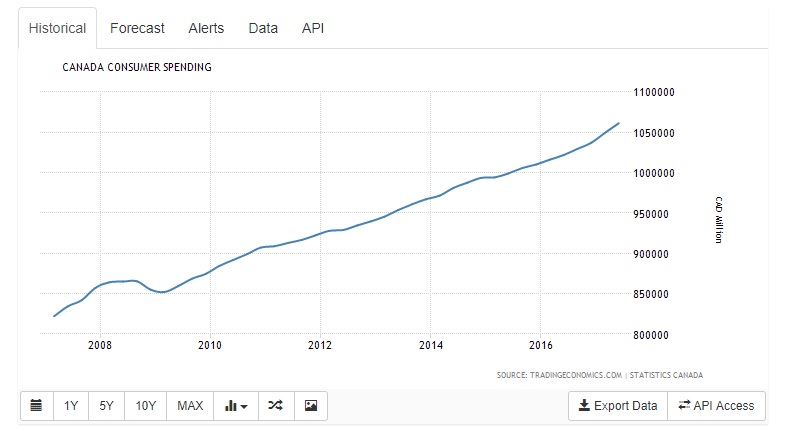

Exports make up about 30% of our overall GDP, whereas consumer spending accounts for about 58% of it. So while our export sector has garnered a lot of recent attention for having finally awakened from its long slumber, we as consumers have a much bigger impact on our economy, and our spending has fuelled most of its momentum since 2008. (The chart below pretty well sums it up.)

Consumer spending is funded in one of three ways: 1) with rising incomes, 2) with a reduction in saving, or 3) with increased borrowing.

Let’s look at how each has contributed to our robust consumer spending growth over the last ten years.

Rising Incomes: Since the start of the Great Recession, our overall consumer spending has risen by about 23% while our average incomes have increased by a little more than 10%. So while rising incomes have contributed to the growth in consumer spending, they haven’t been the main driver.

Reduced Savings: Over that same period, our average household saving rate increased from about 3% to about 4.5%, so whatever Canadian consumers were spending was not, on average, coming from a drawdown of their savings.

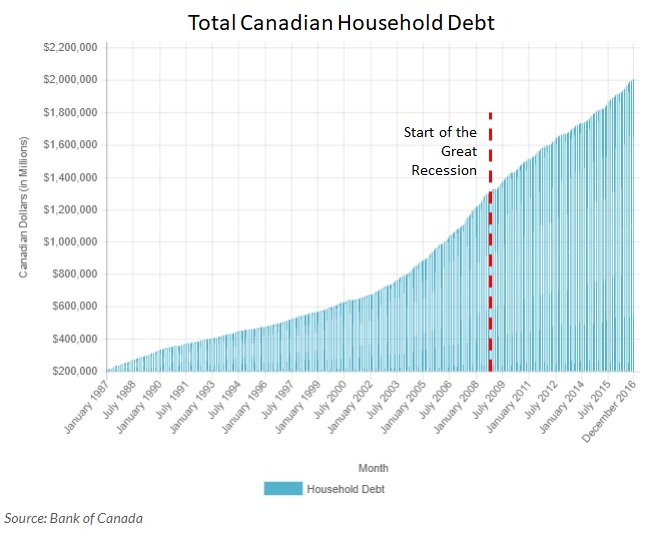

Household Debt: Household debt, which comprises both residential mortgage debt and other consumer debt (such as credit cards, car loans and student loans), has grown by a whopping 65% since 2008 (see chart below).

Let’s briefly recap how the small bars on the bottom left corner of the graph became the big bars on the far right corner of the graph.

Even before the financial crisis, household debt was rising at a rapid rate. When the crisis hit, the BoC dropped our policy rate to emergency levels to stave off the risk of outright financial calamity and, in retrospect, they would do that again in a heartbeat.

Then, after the initial shock, when our export volumes tanked and our economy stumbled, those ultra-low rates fuelled debt-financed consumer spending, which helped offset lost economic momentum elsewhere.

This too seemed a reasonable trade off at the time. It avoided a sharper slowdown and our household balance sheets stayed in relatively good shape because asset prices were rising, and, at ultra-low rates, the additional debt was still affordable for most borrowers.

Fast forward to today.

Our policy makers now see our household debt levels as the biggest threat to our future economic stability. But thus far, five rounds of mortgage rule changes haven’t slowed our rate of debt accumulation to their satisfaction. So a sixth round is now imminent, and if that doesn’t do the trick, I have no doubt that a seventh round will follow. (Interestingly, the regulators don’t seem to have even considered changes to other household debt, such as restrictions on the lengthy amortization periods of unsecured loans.)

To be clear, I think our policy makers are right to be concerned about our household debt levels and I have supported the five rounds of mortgage rule changes made thus far. I am less sure about the efficacy of the changes coming in round six, but more on that in a future post.

The key question to be answered is, as our rate of household-debt accumulation slows, what will offset the inevitable drop in consumer spending that will accompany it?

We haven’t seen convincing evidence that it will be rising incomes.

It’s true that incomes rose by 2.2% on a year-over-year basis last month but they have barely outpaced our rates of inflation over the past several years. If higher incomes are the answer, they will need to rise at a much faster rate to offset the impact that reduced borrowing will have on our overall consumer spending levels.

The BoC cites encouraging soft data, like rising business confidence and plans for increased business investment, as reassuring signs that growth will come from non-consumer sources. But if consumers stop spending at the same time as exports are slowing, it’s hard to imagine businesses following through on their intended plans.

Bluntly put, as our rate of borrowing decreases, I expect that consumer spending will decrease right along with it. This will cause our overall economic momentum to slow and when that happens, the BoC will be more likely to contemplate rate cuts than rises.

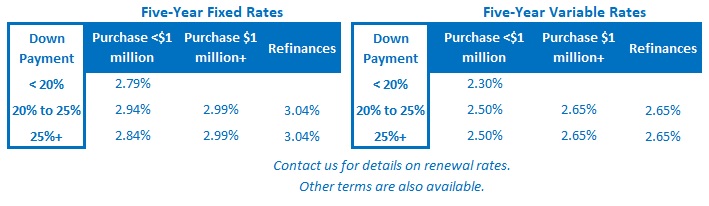

Against that backdrop, low mortgage rates may serve as a thin silver lining on what will otherwise be cloudy economic days ahead.

I hope I’m wrong.

I just don’t think I will be.

The Bottom Line: Our economic momentum has been boosted by debt-fueled consumer-spending growth since the start of the Great Recession and our household debt levels have risen sharply as a result. Concerns about instability risks have led to policy changes that are designed to slow further household debt accumulation. But as these changes take hold, consumer spending, which accounts for more than half of our total GDP, will also slow. When that happens, I think the BoC will be more likely to focus on lowering rates to stimulate inflation rather than on raising rates to curtail it.