Why October’s Strong Employment Data May Not Matter to the Fed

November 11, 2013Monday Morning Interest Rate Update (November 25, 2013)

November 25, 2013 Most of us understand intuitively that you can’t solve a debt crisis by creating more debt any more than you can cure alcoholism by drinking more alcohol. That’s why the U.S. Fed’s quantitative easing (QE) programs make so many of us nervous, even as QE continues to push stock prices higher and interest rates lower. The more I learn about this subject, the clearer it becomes that we are living on borrowed time (pun fully intended).

Most of us understand intuitively that you can’t solve a debt crisis by creating more debt any more than you can cure alcoholism by drinking more alcohol. That’s why the U.S. Fed’s quantitative easing (QE) programs make so many of us nervous, even as QE continues to push stock prices higher and interest rates lower. The more I learn about this subject, the clearer it becomes that we are living on borrowed time (pun fully intended).

That is the fundamental challenge that I now grapple with on a weekly basis when writing about the factors around the world that influence Canadian mortgage rates. Of all of these outside forces, there is no doubt that QE is the proverbial elephant in the room.

On the one hand, QE (along with the Fed’s dovish forward interest-rate guidance) make it highly likely that our mortgage rates, especially our variable-mortgage rates, will stay at today’s ultra-low levels for the foreseeable future. On the other hand, these low rates are a direct result of unprecedented monetary expansion by the U.S. Fed that has produced few of its intended benefits while perpetuating massive but as-yet-unquantified costs for future generations.

This quote pretty well sums it up: “Never in our history has so much money been spent to produce so little good, and the full bill for this failed policy has yet to arrive. No such explosion of debt has ever escaped a day of reckoning and no such monetary surge has ever had a happy ending.” – Phil Gramm and Thomas R. Saving via The Wall Street Journal, November 21, 2013.

Queue the ominous-sounding music.

Look, I’m not trying to freak you out. I’m only trying to offer my take on why QE isn’t working, why any related benefits these programs produce, like ultra-low mortgage rates, will prove transitory in the fullness of time, and why QE threatens to produce negative consequences that will match these massive programs in scale. Gaining a good understanding of QE’s fundamental flaws will enhance our knowledge of the current situation, and help us be nimble in the face of the approaching but probably still distant storm.

Let’s start with the incredibly shrinking wealth effect.

The Fed continues to believe that if QE drives stock and asset prices higher, it will produce a “wealth effect” that will make people feel richer and cause them to increase their spending and consumption.

Only so far it hasn’t.

In fact, U.S. consumer spending growth has actually decelerated over the past three years.

That’s primarily because, in practice, QE has only made the already rich marginally richer. And unlike the middle class and the poor, the rich don’t tend to spend their extra income because their needs are already met. In the simplest terms, since the wealth effect created by QE hasn’t materially altered the standard of living of its beneficiaries, it has had little impact on their rates of consumption.

While the positive impacts of QE have not materialized, the negative effects are easier to see. Here are a few examples:

- When QE is used to push interest rates down to lower borrowing costs as a way to support house prices, it also reduces the incomes of savers and pensioners. This diminishes their purchasing power, causing them to reduce consumption.

- These same low interest rates result in much lower incomes to pension plans. This threatens their solvency and forces their sponsoring employers to greatly increase their contributions – if they can. These greater contribution requirements reduce the corporate funds available for business investment and expansion. In fact, we are now seeing situations where the size of the pension obligations greatly exceeds the total value of the underlying business. And it’s not just businesses that suffer in this way. The recent bankruptcy of Detroit was caused in large part by its pension problems and there is a line-up of other municipalities behind Detroit that are suffering from the same QE-exacerbated disease.

- When QE causes would-be retirees to postpone retirement because their savings aren’t producing enough income to live on, their jobs aren’t passed on to young workers who are trying to enter the workforce. Historically, twenty-somethings have spent a disproportionately large percentage of their income on consumption; but if they’re not working, they’re not spending.

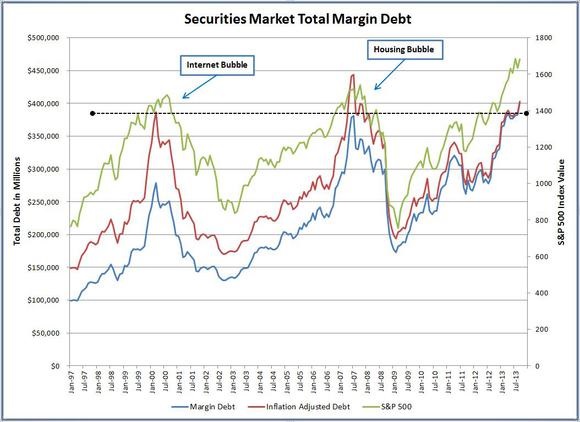

- When QE is used to push interest rates down, it lowers the returns that banks can make through traditional lending. Predictably, U.S. banks have responded by reducing their loans to small, non-corporate businesses, which are the primary drivers of U.S. job creation. Instead, these banks (and others) have sought out leveraged, speculative investments, which offer higher yields but come with significantly higher risks that could one day threaten the stability of the U.S. financial system. The graph below, although it is not specific to banks, illustrates the principle (courtesy of Motley Fool).

This disconnect between what the Fed expected from QE and what it actually got helps explain why the Fed’s economic growth forecasts have been so wildly off the mark during the recovery. Nonetheless, the Fed continues to operate under the fundamentally flawed assumption that QE will trigger a wealth effect that will increase demand and push the U.S. economy towards escape velocity – notwithstanding a significant and growing amount of evidence to the contrary.

While we’re on the topic of the unintended consequences of QE, would you be surprised to learn that instead of fuelling growth, QE may actually be choking it off?

Several recent studies show that economic growth slows when the combination of public and private debt exceeds about 260% of GDP, a level the U.S. economy crossed in 2000. Since then, U.S. GDP growth has averaged only 1.8% per year, compared to an average of 3.7% from 1870 until the late 1990s. At the same time, average household incomes have fallen by 4.3% while the income gap between rich and poor Americans has accelerated. (Stats taken from the Third Quarter 2013 Hoisington Investment Management Review and Outlook.)

Excessive debt levels eventually dominate an economy’s resources and choke off other forms of more productive investment. Unsustainable debt levels also raise fear and uncertainty about the future and cause businesses to hoard cash that they might otherwise have invested in growth and productivity enhancements.

QE is allowing U.S. debt levels to increase at an alarming rate and this will continue to hamper the growth prospects for the already over-indebted U.S. economy. But that’s actually the happier side of QE’s two-sided coin. The other side involves the inevitable unwinding QE and painful process of trying to reduce its influence on markets.

QE is an addictive stimulus for markets and its eventual withdrawal isn’t going to be pretty.

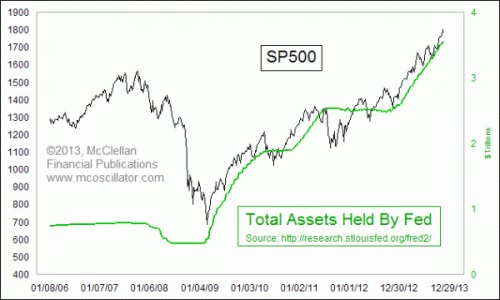

That’s why it was hard to believe that the Fed was surprised at the reaction when it first told markets that someday QE would end. Ben Bernanke seems to have really believed that he could take the punch bowl away while the band played on. Check out this correlation between the expansion of QE and stock prices (hat tip to Tom McClellan for these charts).

Anybody notice a correlation between QE expansion and stock prices?

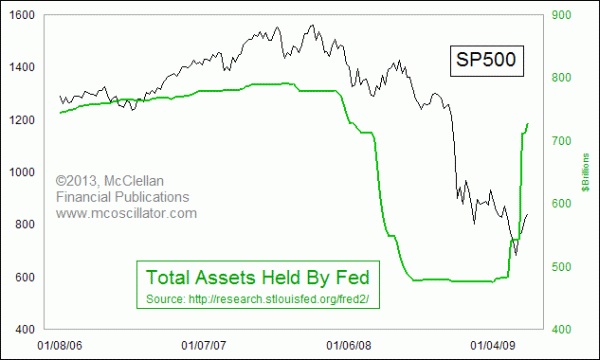

And here is a look at what happened to stock prices over the last period when the Fed tried to sell of its treasury debt.

QE has grown so big that it is now a market colossus. That’s what you get when an activist Fed promises to use QE to restore growth, fix unemployment and offset Washington’s fiscal intransigence. At the rate it’s going, the Fed will probably be promising to wash everyone’s car by mid-2014.

The Fed started QE with the best of intentions and most observers agree that the first round was necessary to avoid a depression-like economic meltdown. But then the Fed started responding like an over-protective parent trying to use the same weapons to stave off every economic setback. In reality, the Fed’s main monetary policy tools are much more suited to curbing excess demand and combating rising inflation than they are to reversing disinflation and reducing over-indebtedness.

The Fed has over-asserted its monetary influence in trying to avoid necessary U.S. economic pain and QE has evolved into an immovable lynch pin that is holding together what little global economic momentum the US enjoys. Regardless, at some point QE will have to be tapered and when that day comes, QE will not go gently into that good night.

When the Fed tries to slow QE, most of the experts I read predict that we’ll get something on a scale between turbulence and chaos: Emerging markets will see panicked outflows of capital, world-wide bond yields will snap higher, stock markets will sell off, and margin calls on speculative investments will remind us all of Warren Buffet’s famous observation that when the tide goes out, we’ll see who has been swimming without their shorts on.

The longer the Fed waits, the more severe the eventual day of reckoning will be. Just as with an addictive drug, QE’s very limited benefits shrink with each new round of purchases while the inevitable pain of its eventual withdrawal will continue to grow.

When countries become over-indebted, there are only three ways to solve the problem: Pay it all back using a combination of higher taxes and deep spending cuts (there is not enough courage or cooperation in Washington to do either), default (which thankfully would be a violation of the U.S. constitution), or inflation (bingo!).

“Inflation is taxation without legislation” – Milton Friedman.

Inflation offers a tempting solution for governments because it is a largely invisible way to expropriate wealth from citizens through higher prices. Government tax revenues rise with inflation, as do hard assets, but cash and debt lose their value. It seems clear to me and most of the expert observers that I read that the Fed’s hidden agenda is to create higher inflation. They just can’t admit it openly. After all, the Fed’s primary mandate for most of its existence has been to fight inflation and to maintain price stability.

We already see inflation in just about everything but the official CPI. Higher stock, real estate and commodity prices are today’s bi-products of ultra-loose monetary policy but this is only stage one. Inflation won’t really kick in until we see an increase in the rate at which all of the Fed’s excess liquidity starts circulating throughout the economy.

This speed of circulation is referred to as the velocity of money and today it is at a fifty-year low. The experts I read say that the velocity of money always reverts to its long-term average over time and when that happens, stage two begins. This is when the Fed’s ability to assert control over market forces will be truly tested.

For now, stage two may still be a long way off. The U.S. will be able to control its monetary policy experiments longer than any other country because the U.S. dollar is the world’s reserve currency and because most investors around the globe still see the Greenback and U.S. Treasuries as safe-have assets. But that was also true of the Roman empire centuries ago and the British empire more recently and new Federal Reserve Chairwoman Janet Yellen would be wise to heed this warning:

“All great power has to do to destroy itself is persist in trying to do the impossible.” – Stephen Vizinczey via The Four Horsemen documentary.

The other relevant observation, which I hesitate somewhat to write, is that the definition of stupidity is doing the same thing over and over again while expecting a different result. Well, there, I said it. More QE anyone?

The question for my readers is, what do we do with this knowledge? Do we line up with the Fed and opt for a variable-rate mortgage, believing that it can continue to keep short-term rates at ultra-low levels for years to come? Those who do are well advised to plough their interest-rate saving back into their mortgages and reduce their principal as rapidly as possible. In the face of uncertainty, it’s always best to make hay while the sun shines.

On the other hand, while locking in a fixed-term rate will be more expensive now, it could also end up being the deal of a lifetime if mortgage rates rise sharply. It is impossible to know for sure how the timing will work but the sequence of events seems clear. The Fed will keep rates artificially low until either it creates significantly higher inflation or until bond-market investors revolt. I suspect that either outcome will still be well off in the future but when the end of our low-rate era is finally reached, the Fed will no longer be calling the shots.

The best of both worlds for those who can sleep well with the risk and who can afford the cost if the market turns against them is to go variable now but make sure that you have someone watching developments for you on a daily basis so that you can make a switch when and if prospects change.

Five-year Government of Canada (GoC) bond yields fell by two basis points last week, closing at 1.76% on Friday. Lenders continue to lower their five-year fixed rates and these terms are now available in the 3.30% to 3.45% range, depending on terms and conditions which can produce a wide variation in borrowing costs over the life of a mortgage.

Five-year variable rates are available in the prime minus 0.55% range (which works out to 2.45% using today’s prime rate of 3.00%). Several lenders recently lowered their variable-rate discounts to bring them more in line with market rates and when that happens, wider discounts often follow as competition for this business heats up.

The Bottom Line: Today’s ultra-low mortgage rates should be with us tomorrow, next week, next year, and maybe for several more after that. But then? I am convinced that U.S. monetary policy has passed the point of no orderly return. When market forces eventually wrest control away from the Fed, the most likely scenario will be sharply higher inflation and the higher mortgage rates to go with them. Forewarned is forearmed.

2 Comments

thanks for the commentary. for more info on the lack of traction coming out of QE, see Richard Koo’s work on balance sheet recessions. monetary policy has negligible impact in such deleveraging processes.

i agree that fixed rates will spike sharply (esp considering less liquidity now in funding markets given recent policy moves) and that variable rates are speculators, prone to any market catalyst.

in turn, makes me wonder why canadians are not more worried about housing affordability/debt overhang.

Hi Mick,

My guess is that many people think that higher mortgage rates are still a distant threat. Thanks for the Richard Koo recommendation. I will check him out.

Dave