The Fed Talks Taper and Bond Yields Soar

September 27, 2021Canadian Employment Surges and Bond Yields Spike Again

October 12, 2021 Last week we learned that US inflationary pressures continued to rise in August.

Last week we learned that US inflationary pressures continued to rise in August.

The US headline consumer price index (CPI) fell from 5.4% to 5.3%, but the personal consumption expenditures (CPE) index, which is the US Federal Reserve’s preferred inflation measure, rose from 4.2% to 4.3%, marking its highest level in thirty years.

In a speech last Wednesday, Fed Chair Powell continued to attribute the inflation spike to supply-chain disruptions, and he reiterated the Fed’s belief that these will prove transitory. But he also acknowledged that “it’s very difficult to say how big the effects will be in the meantime, or how long they will last”.

Bond-market investors have grown tired of waiting for inflationary pressures to ease. Spiking inflation has eroded their returns, and they are now driving bond yields higher to restore them.

That development forces our central bankers to walk an increasingly fine line.

They need financial markets to believe that they can keep inflation under control and bring it to heel if required once supply bottlenecks are eased. But those reassurances have increasingly fallen on deaf ears.

So why don’t the Fed and the Bank of Canada (BoC) address the issue by ending their quantitative easing (QE) programs and moving up their rate-hike timetables?

Well, for starters, it’s not even clear that tightening monetary policy now would have much impact on the sources of today’s inflationary pressure. Frances Donald, Manulife’s Global Chief Economist, explained this well in her tweet last week:

The Fed can hike interest rates all it wants, it’s not going to make it rain in Brazil, open ports in China, find truck drivers in the UK, change covid-0 policies in Australia. Bet that the Fed will hike rates if you want, but don’t bet it will help this supply-driven inflation.

If the Fed and the BoC don’t think tightening will alleviate inflationary pressures, why risk stifling momentum?

Our recoveries are still far from complete, and inflation isn’t the only risk.

Tightening too soon could kill the recovery and plunge us back into recession. The Fed learned during the Great Depression, when it prolonged the downturn and triggered deflation by tightening prematurely.

If they are forced to pick their poison, central bankers readily acknowledge that their monetary-policy tools are much better suited to fighting inflation than deflation.

Here are three key areas that will be materially impacted by tightening:

- Growth

The US and Canadian economies were expected to rebound quickly coming out of their lockdowns, but it has become increasingly clear that a lot of the initial momentum was attributable to heavy doses of fiscal stimulus, which are now being withdrawn.

The Fed has consistently lowered its GDP forecasts for 2021, most recently from 7% to 5.9%, and even that looks like a stretch when we remember that the US economy won’t have nearly as much stimulus to bring it home.

Canadian GDP growth has been even weaker, although mostly because we experienced more lockdowns.

Our GDP contracted by 1.1% year-over-year in the second quarter and edged down a further 0.1% in July. (Stats Can is estimating that our GDP growth will rebound to 0.7% in August, but its initial estimates have been wildly off the mark of late, so that number is best taken with a grain of salt.)

In its July Monetary Policy Report (MPR), the BoC projected our 2021 GDP growth at 6%. It will be taking an axe to that number when it releases its next MPR later this month.

Monetary-policy tightening would be an additional headwind for our economies at a time when growth is slowing more than expected.

- Employment

Much of the inflation narrative has centred on the idea that wages are heading inexorably higher, but thus far, the anecdotal feedback that employers must raise wages and/or offer incentives to lure workers back hasn’t shown up in the overall wage data. Labour costs are still largely contained.

We are just now reaching the point in both Canada and the US where huge swaths of unemployed workers will see their benefits expire.

Logic says that many of those workers will now be compelled to rejoin the workforce, which should help alleviate labour shortages and reduce upward pressure on labour costs.

This large-scale reintegration of workers marks a critical turning point for our labour markets, and talk about tightening won’t help it along.

- Spending

Consumer spending accounts for approximately 70% of US GDP and it grew by about 10% on a year-over-year basis over the first two quarters of 2021. But it then slowed to -0.1% in July, and the most recent data show US spending tracking closer to 2% over the second half of this year.

Canadian consumer spending is farther behind. We are still well below our pre-COVID spending peak (whereas US consumer spending is now well above its pre-COVID threshold).

The spending roar that accompanied our reopenings has now been reduced to a meow.

Against that backdrop of slowing growth, the expiry of unemployment benefits, and reduced consumer spending, the Fed just confirmed that the US employment recovery has somewhat suddenly met its definition of “substantial further progress”, and that QE tapering will soon be appropriate.

This marked a significant shift for the Fed. Only two weeks prior, in his speech at Jackson Hole, Fed Chair Powell expressed concern about the Delta variants’ “evolving risks” and assessed that US employment still had “much ground to cover”.

From my desk, it looks as though the Fed capitulated to what must have been tremendous behind-the-scenes pressure to slow the rate at which it is pumping liquidity into the financial system, because the timing doesn’t otherwise make sense, based on the data.

To be clear, the Fed must start tapering at some point (the BoC already has), and if they do it gradually, it may not create enough of a headwind to adversely impact the US economy’s already vulnerable areas.

But there is risk that it could. Especially if it moves too soon or by too much.

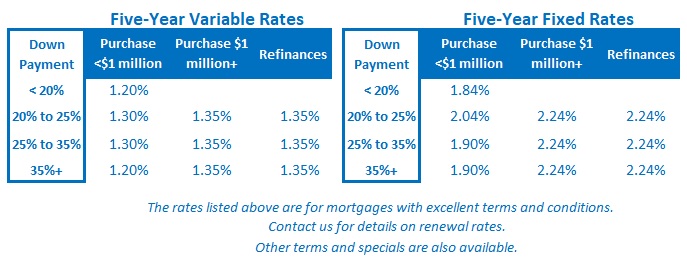

The Fed’s moment of truth will come when it is pressured to start raising rates farther down the road. At that point, the impacts and the stakes will be higher.  The Bottom Line: Five-year fixed rates moved about 0.30% higher last week in response to the recent bond yield run-up.

The Bottom Line: Five-year fixed rates moved about 0.30% higher last week in response to the recent bond yield run-up.

The tug of war between central banks and bond markets may push rates higher over the near term, although there would likely need to be an additional catalyst because the Fed’s tapering announcement has now been priced in.

Meanwhile, variable rates aren’t likely to move for some time yet. The BoC is estimating the second half of next year, but my guess is still that it will take longer.

2 Comments

Thanks for the insight -This is awesome. Rakesh

Glad you found it useful Rakesh.