Why Spiking Inflation Won’t Impact Canadian Mortgage Rates

November 23, 2020Five Mortgage Thoughts of the Day

December 7, 2020There is a growing consensus that the pandemic will end sometime in mid- to late-2021 and that fixed mortgage rates will move higher relatively soon in anticipation of that outcome.

I respectfully disagree with both assumptions.

While I hope I’m wrong, I think the pandemic could continue for longer, and I don’t think fixed mortgage rates will bottom for some time yet.

To explain why, let’s start with an update on potential vaccines, and more importantly, projected vaccination rates.

Last week Prime Minister Trudeau told us to expect that an effective vaccine will become available in early 2021 and that “more than half of Canadians” will be vaccinated by next September.

Bluntly put, this sounds like wishful thinking.

Even if our vaccine acquisition and distribution challenges are overcome, there is no guarantee that the pandemic will end shortly after they are made widely available.

While some Canadians will consent to being vaccinated as soon as possible (myself among them), others will be more reluctant, and experts estimate that herd immunity can’t be achieved until approximately 70% of the population receives their shots.

This recent CBC segment on vaccine hesitancy outlines several of the concerns that Canadians have about being vaccinated. They include:

- I’m healthy. Let people in higher-risk categories get vaccinated.

- I don’t want to be first in line. Let others go first so I can see if there are side effects.

- Vaccines normally take years to develop. These ones came along too fast to be trusted.

- No one can tell me what to do!

Today almost all of us wear masks when we’re indoors in public places, but that’s in part because there is usually someone monitoring at the door, and because we would receive a lot of disapproving looks without one.

Mask compliance is on full public display, but vaccine compliance will not be. That will reduce the social pressure for those on the fence (and I think that group is larger than many assume).

Once vaccinations begin, what happens if stories about a vaccine’s bad side effects (whether true or false) start circulating? Do we really think the nefarious groups who have proven so effective at fomenting discord online won’t make vaccine efficacy their next target?

While I hope I’m wrong, I think getting the majority of Canadians vaccinated will prove more difficult and take longer than generally expected. In the end, developing the vaccines may actually prove to have been the easy part.

For argument’s sake, let’s optimistically assume that we do achieve herd immunity in the second half of 2021. What will happen after that?

Many now predict that we’ll see a recurrence of the Roaring Twenties.

Back then, the world was emerging from both the end of World War One (1918) and the Spanish flu (1920). What followed was a decade of rapid economic growth and accelerating consumer demand that fuelled widespread prosperity.

Many forecasters now predict that a similar decade awaits.

They note that a record spike in our personal savings rate has added excess cash to household balance sheets, and they expect much of that cash to be released into the economy as soon as the pandemic ends, kick-starting a cycle of growth and economic renewal.

This forecast makes sense on first pass because who among us doesn’t look forward to their first post-pandemic restaurant meal, event or vacation? But, as is often the case, a closer comparison between the 1920s and the 2020s reveals some very important differences.

Last week, economist David Rosenberg made some insightful comparisons between the 1920s and now (citing U.S. examples, but Canadian comparisons would be similar):

- At the end of World War One the U.S. economy accounted for half of global manufacturing production after capacity had been decimated in war theatres around the world. There will be no such demand tailwind this time around.

- The U.S. economy never went into full lockdown during the Spanish flu. Back then it was survival of the fittest (and the luckiest) – a more brutal approach for sure, one that made the damage severe and acute but also created conditions for a rapid rebound. This time around, policy makers have chosen to blunt the economic shocks caused by COVID but at the cost of a more protracted recovery.

- The U.S. government entered the 1920s with a debt-to-GDP ratio of 10% whereas today it is over 100%. That minimal amount of debt gave it much more room for tax cuts and stimulus than is available today.

- In the 1920s, half of the U.S. population still lived in rural areas, and the urbanization trend that evolved over that decade provided massive ongoing economic stimulus. We’re heading out of cities this time around.

- The U.S. home-ownership rate was 25% back then compared to 64% today (and it is even higher in Canada). The steady increase in home-ownership rates throughout the 1920s provided another pro-growth trend. Proportionally, there aren’t enough renters left to recreate that tailwind in the decade ahead.

- In the U.S., the average age was 29 years in the 1920s compared to 38 today. Also, in the 1920s, only 7% of the population was over the age of 65, whereas today that number is about to hit 20%. Younger populations spend more than older populations.

To be clear, I do expect a short-term surge in spending when the majority of Canadians are convinced that the pandemic is behind us, and that could easily fuel a temporary surge in growth and inflation that causes bond yields, and the fixed mortgage rates that are priced on them, to rise in response.

But what then?

By the time COVID is in our rear-view mirror, governments and households are going to be so bloated with debt that even a small rise in interest rates will divert a significant amount of capital away from the resources that are needed to drive growth and toward debt repayment instead.

Given that, what will sustain that initial surge in economic momentum once our pent-up cash is spent?

Last year, former Bank of Canada (BoC) Governor Poloz observed that because of the high levels of current debt, the Bank wouldn’t need to raise its policy rate by as much as it had to in the past to bring inflationary pressures to heal – and that was before COVID hit and our debt levels exploded into the stratosphere.

More recently, new BoC Governor Macklem cautioned that our recovery was going to be “long, slow, and painful” and he reassured Canadians that the Bank will be with us for the long haul. Does that sound as though he is buying the prediction that the Roaring Twenties awaits?

We can have a lively debate about vaccine release dates and vaccination rates, but the state of our post-pandemic economy and the impact that record levels of debt will have on it seems more readily apparent.

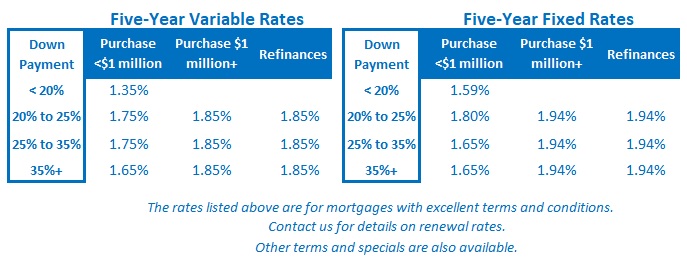

Simply put, if past is prologue, high debt levels will correspond with flat or falling rates, and our policy makers will be much more concerned with having too little inflation, rather than too much of it. The Bottom Line: The recent threat of an increase in fixed mortgage rates never did materialize, and I expect these rates to either remain at their current levels or resume their slow decline over the short-term remainder of this year.

The Bottom Line: The recent threat of an increase in fixed mortgage rates never did materialize, and I expect these rates to either remain at their current levels or resume their slow decline over the short-term remainder of this year.

This belief is bolstered by the BoC’s commitment, which it reiterated last week, to focus its quantitative easing purchases, in part, on the Government of Canada bond yields that our fixed mortgage rates are priced on.

The Bank also reiterated that it expects its policy rate, which our variable-rate mortgages are priced on, to remain at its current level until some time in 2023.