Why the Bank of Canada and the Bond Market Still Don’t See Eye To Eye

June 3, 2019If the U.S. Federal Reserve Drops Rates, Will the Bank of Canada Have to Follow?

June 17, 2019 If you are keeping an eye on mortgage rates, then you have probably been reading a lot about inverted yield curves lately.

If you are keeping an eye on mortgage rates, then you have probably been reading a lot about inverted yield curves lately.

This is a phenomenon that doesn’t occur very often. In normal markets, longer term interest rates are higher than shorter term rates. A yield-curve inversion happens when the yields offered on longer-term bonds drop below the yields offered on shorter-term bonds.

At first glance, this is counterintuitive. Why would I buy a bond that ties up my money for longer and also gives me a lower return?

Well … since you asked …

Let’s assume that today I offered you the choice between a five-year Government of Canada (GoC) bond that pays 1.35% and a one-year GoC bond that pays 1.65%. If you were investing with a long-term time horizon, the only reason you would opt for the five-year bond would be if you thought that you would have to renew your one-year bond at a yield lower than 1.35% in a year’s time.

There are different combinations of factors that cause a yield curve to invert, but in every instance the inversion is underpinned by the expectation that both inflation and future interest rates will fall.

While on first pass this all might sound like good news if you’re in the market for a mortgage, it is not good news for the economy as a whole. Yield-curve inversions are almost always followed by periods of slowing economic growth or, worse, outright recessions. (As a reminder, a recession is defined as a period of economic decline where GDP falls for at least two consecutive quarters.)

The U.S. yield curve has inverted ten times since 1960, and in nine of those ten instances a U.S. recession has followed. (Interestingly, Canadian yield curve inversions aren’t as reliably predictive.)

Fast forward to today.

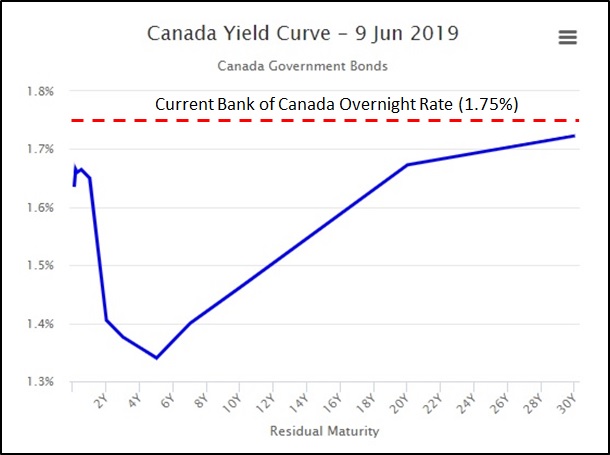

The U.S. yield curve inverted in mid-March of this year for the first time since mid-2007 (anyone need a reminder about what happened to the U.S. economy shortly after that?), and the Canadian yield curve inverted out to about the 18-year term mark shortly thereafter. (See chart.)

The Bank of Canada (BoC) noted this yield curve inversion in its most recent Monetary Policy Report (MPR), but it also downplayed its signalling power in the current environment.

The Bank noted that yield-curve inversions are typically caused by “short-term interest rates rising persistently above long-term rates, rather than because long-term rates were falling, as has been observed over the past couple of months”.

Let’s dig a little deeper into that statement.

When shorter-term rates rise above longer-term rates for an extended period, it is most often because a central bank is deliberately trying to slow its economy in order to ease inflationary pressures. This is easier said than done because monetary-policy tightening is not an exact science. Rate hikes take time to work their way through an economy, and by the time a tightening cycle’s full impact is realized, it is too late to change course if the economy has slowed more than expected (because the stimulative benefits from subsequent rate cuts also take time to accrue).

That’s why recessions are most often caused by monetary-policy oversteps.

In its latest MPR, the BoC argues that our current yield-curve inversion was triggered this time by falling long-term rates, not by rising short-term rates. It asserts that in both the U.S. and Canada, “structural factors such as increased public and private sector demand for high-quality government securities, have contributed to lower long-term yields.”

While the BoC’s observation is likely a contributing factor, yield curves are inverting in many of the world’s largest economies, and this makes it less likely that U.S./Canada-specific structural factors are the primary cause.

I operate under the default assumption that the simplest explanation is usually the best one, and through that lens I think bond investors are simply more pessimistic about our economic prospects than the BoC is (which I wrote about in detail in last week’s post).

That pessimism is partly based on concerns about our policy maker’s attempts to wean our economy off debt-financed growth. While there are encouraging signs that macro-prudential changes have reduced our rate of debt accumulation, the BoC’s forecast that the concomitant drop in household spending will be offset by a rise in exports and business investment seems more hopeful than credible thus far.

Increased pessimism is also evident in the U.S. bond market. David Rosenberg captured its current mood well when he recently wrote that “bull markets do not die of old age, they become more vulnerable to external shocks, financial excesses, and policy missteps. We are in the camp that we already have seen all three – the ever-escalating trade war as the shock, corporate debt as the excess and overtightening by the Fed as the policy misstep.” (As I read that, I thought that he could just as easily have written the same about Canada.)

U.S Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell further stoked the belief that U.S. rates are headed lower over the longer term in a speech last week when he said, “My FOMC colleagues and I must—and do—take seriously the risk that inflation shortfalls that persist even in a robust economy could precipitate a difficult-to-arrest downward drift in inflation expectations”. Powell added, “The next time policy rates hit the ELB – and there will be a next time—it will not be a surprise. “ (Note: ELB stands for Effective Lower Bound, which is banker speak for 0%.)

So how should our inverted yield curve affect Canadian mortgage borrowers’ decisions on fixed vs. variable rates and on longer vs. shorter mortgage terms?

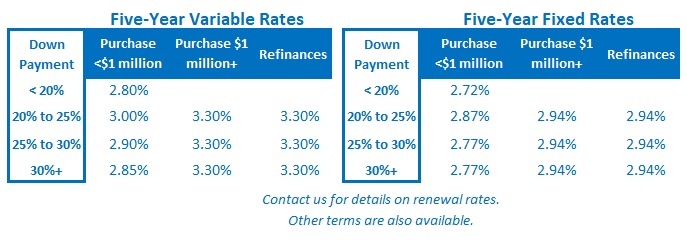

In the current environment, five-year fixed rates are lower than shorter-term fixed rates, and in most cases also lower than the starting rates for their five-year variable-rate equivalents. Even sophisticated borrowers who put a lot of time and energy into optimizing their mortgage-rate strategy are opting for the boring old five-year fixed rate today (as I explained in this recent interview with Globe and Mail personal finance columnist Rob Carrick).

That’s not to say that you can’t make the case for shorter-term fixed rates or variable rates. The bond futures market is still betting that the BoC’s next rate move will be a cut, and if we fall into a recession, more cuts will surely follow. But experience has shown me that it’s tough for most borrowers to accept a higher rate today on a bet that they will be better off later for having done so. (That truism also explains why ten-year fixed rates have had limited appeal, which I wrote about here).

The Bottom Line: In the strange times in which we find ourselves, today’s inverted yield curve has made five-year fixed mortgage rates cheaper than all of the other available rates and terms. Furthermore, it indicates that bond-market investors expect rates to continue falling. That expectation implies that we will see choppy economic waters ahead, but it is also good news if you happen to be in the market for a mortgage.

1 Comment

I love the insight and objective angles. Very useful while I look at whether to accept my bank’s offer of an early renewal – they’re trying to influence me into accepting a 3yr rate. I think I will look at a 5 yr rate – but I’m not due until October. It looks like it may be worthwhile to wait until at least the July 10th update from the BoC.

Thank you.