A Recap of Recent Posts

March 29, 2021The Stress-Test Rate Used for Uninsured Mortgages Is About to Rise

April 12, 2021The Bank of Canada (BoC) is facing increased pressure to accelerate its rate-hike timetable to slow house-price appreciation and stave off housing bubble risks.

Its promise to keep rates at ultra-low levels for years to come has combined with the growing belief that house prices will rise forever to form a potent, intoxicating mix.

Buyers are also haunted by the warning that they must buy now or be priced out forever, and would-be sellers who hold on to their properties are quickly rewarded with more gains.

There are other COVID-related factors that are helping to push prices higher.

Until now, young Canadians who were determined to become homeowners had to resign themselves to extended commute times because they could only afford to buy in areas that were far from the urban centres where they worked, a phenomenon referred to as “drive until you qualify”.

But almost overnight, that has changed.

The recent shift to work-from-home employment has greatly reduced the need to spend long hours fighting traffic and therefore increased the appeal of real-estate that is farther field, creating a surge in demand that most of these areas have never seen before.

As house prices continue to skyrocket, many observers worry that the current run-up will end in tears and are imploring policy makers to cool prices before a crisis hits.

Here are my thoughts:

- Right now, the BoC has bigger problems to worry about.

The BoC’s primary concern, for as long as we remain mired in the pandemic, is to minimize damage to our economy and avoid a repeat of the Great Depression.

Against that backdrop, it knew (in fact, it expected), that slashing rates to ultra-low levels would stimulate demand for housing. Former BoC Governor Stephen Poloz plainly acknowledged in a recent interview that “If the side-effect [of emergency stimulus] is a hot housing market, that’s one I’ll take every day”. He added “we could see signs of speculation, but we have to accept that because otherwise we would have a really, really bad recession”.

Current BoC Governor Tiff Macklem did finally express some concern last week when he conceded that some Canadians are “expecting the kind of unsustainable price rises we’ve seen recently [to] go on indefinitely” and he acknowledged that “we are starting to see some early signs of excess exuberance”.

Even so, the Bank’s options for addressing speculative real-estate froth are limited. If it raises its policy rate to cool house-price appreciation, that cost increase will also impact other vulnerable areas of our economy that still need the crutch of cheap borrowing to help cushion against COVID’s negative impacts.

Simply put, monetary policy is too blunt a tool for the delicate work of reining in housing demand.

Instead, the Bank has maintained the view that macro-prudential policy adjustments, otherwise known as mortgage rule changes, are better suited to the job.

- The stress test is a powerful mitigant.

In late 2016 and again in early 2018 our federal government introduced mortgage rule changes in order to ensure that mortgage borrowers could withstand higher rates.

Today, you must prove that you have enough income to borrow at the stress-test rate of 4.79% before you are then allowed to borrow at actual rates in the 1.5% to 2.25% range. This gap ensures that borrowers can afford at least a doubling in mortgage rates by their renewal date (and without factoring in their reduced principal balance).

This onerous stress-test standard ensures that even a significant spike in mortgage rates is unlikely to trigger the wave of mortgage defaults that caused the US housing crisis in 2008.

That isn’t to say that higher rates wouldn’t negatively impact borrowers, because discretionary spending may have to be cut back, but the stress test greatly reduces the risk that mortgage payments will become truly unaffordable.

- Other past mortgage rule changes are helping to limit taxpayer exposure.

When the mortgage stress test was first introduced in October 2016, our federal government also announced that it would limit the availability of mortgage-default insurance to purchase transactions of less than $1 million and cap the maximum amortizations on default-insured mortgages at 25 years.

(As a reminder, our federal government backstops the mortgage-default insurance policies that reduce lending costs and lower associated mortgage rates.)

Over time, those changes have led to a gradual reduction in taxpayer exposure because as prices rise, fewer properties are eligible for default insurance. The same is true when an increasing number of borrowers require amortizations of more than 25 years in order to qualify.

At least in that context, higher house prices are actually helping to reduce taxpayer risk.

- Bad changes would be worse than no changes.

There is no denying that we have widespread supply/demand imbalances, that house-price acceleration is shutting too many Canadians out of the market, and that we should be worried about the growing belief that houses prices will rise forever. But our policy makers should resist the urge to be seen to be doing something when such actions could make things worse.

Bluntly put, it would make no sense for the BoC to start hiking rates to slow house-price acceleration because too many other vulnerable parts of the economy will be negatively impacted. Also, reversing course so soon after doubling down on its promise to keep rates low would greatly diminish its future credibility.

Enhancements that are aimed specifically at first-time buyers would really only be beggar-thy-neighbour policies that favour one group in exchange for disadvantaging other groups who are equally impacted by affordability (such as growing families who are stuck in small condos).

More broadly, any policies that increase affordability will just drive prices even higher, and increased restrictions on borrowing will likely have limited impact because determined borrowers will find creative ways to overcome new obstacles such as co-signers, alternative private lenders and/or increased down payments.

- While there is no magic bullet, more can be done.

There is no single solution that all the housing market experts have somehow missed, but more can be done.

While I certainly don’t favour the introduction of a capital gains tax for typical homeowners, I think it is fair to tax buyers who flip houses over short periods and rely on those profits for their primary source of income. In such cases, it seems only fair that their regular incomes should be taxed the same as any other income.

I think national non-resident and/or vacancy taxes would also help. It seems incongruous that properties should sit empty when the demand for housing is running so far ahead of supply.

I agree with those who think we should do away with our blind-bidding process, which can often cause buyers to needlessly overpay for the most expensive asset most families will ever own. I also see the logic in raising the down-payment requirements for investors who are purchasing multiple investment properties, thereby reducing their incremental borrowing capacity.

I think it is unconscionable that it is apparently easy to launder money through Canadian real estate transactions, as exposés in British Columbia and Ontario have revealed. I would add that I found that news strange because I am required to provide extensive bank and investment statements showing the origin of every penny being used in each transaction, and those requirements account for the vast majority of the paperwork we process on each deal. That said, there are some gaping loopholes, and our authorities have left them open for too long.

Increased supply through carefully managed zoning and building code updates, and improved transit to allow populations to spread farther afield offer the greatest potential, but those efforts will take years to bear fruit. In the meantime, I’m optimistic that the work-from-home trend will benefit affordability more profoundly than we yet realize.

For now, here’s hoping that our macro-prudential policy makers come up with changes to help curb speculation, increase occupancy rates, reduce fraud and raise taxes where appropriate. They’ve still got time. But if they dither, or get it wrong, market forces will at some point find another way to address the imbalances.

Let’s all root for the policy makers.

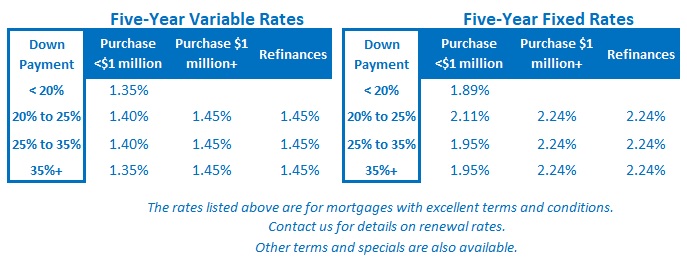

The Bottom Line: Five-year fixed rates inched a little higher last week but now that the five-year Government of Canada yield they are priced on has levelled off, that should be it for a while.

Meanwhile, five-year variable rates remain nailed to the floor, and there is no reason to expect that to change after the BoC recently doubled down on its low-rates-for-longer guidance.