Federal Election Primer: Mortgage-Specific Proposals

September 13, 2021The Fed Talks Taper and Bond Yields Soar

September 27, 2021Last week Statistics Canada confirmed that our overall inflation rate, as measured by our Consumer Price Index (CPI), spiked to 4.1% in August.

Inflation is at the forefront of people’s minds these days, and it has caused many to predict that higher mortgage rates are on the way.

I continue to disagree with that assessment.

It is certainly possible that a stubborn inflation spike could push the Government of Canada (GoC) bond yields, which our fixed mortgage rates are priced on, higher over the near term. But even if that happened, I wouldn’t expect the run-up to last very long.

Here are ten thoughts to support my admittedly contrarian view.

- The Bank of Canada (BoC) is focused on a specific type of inflation.

The most prominent examples of inflation today are in hard assets, such as house prices, but they don’t get counted in the inflation data the BoC uses to measure price stability.

In fact, the Bank doesn’t even consider our overall CPI measure to be the best inflation gauge.

Instead, it relies on three sub-measures of core inflation to smooth out short-term fluctuations and anomalies in the data.

The BoC’s favourite measure of core inflation is CPI-common, which it explains “helps filter out price movements that might be caused by factors specific to certain components”.

Last month CPI-common came in at 1.8%, and it that is slightly below its pre-COVID level.

- Our inflation spike is not broad based.

A lot of the inflation we are seeing today is in the prominent items that catch the public’s attention, but thus far, it is limited to the areas that are most directly being impacted by COVID-linked supply bottlenecks and shortages.

Economist David Rosenberg noted last week that “the inflation bulge is really occurring in less than 30% of the CPI (the visible areas that garner all the press attention), while the other 70% is not really doing that much at all from a pricing standpoint”.

- The commodity price run-up is easing.

Today’s inflation narrative was originally stoked by higher commodity prices, but most of them are now falling back toward their previous levels and here may be plenty of air left under them yet.

Consider that China, the world’s marginal buyer of commodities and the driver of global growth for the past decade, has seen its momentum slow sharply this year.

- Labour costs are still contained.

Labour is the single most pervasive cost in an economy and there have been widespread reports of employers having to increase wages and/or offer additional incentives to lure workers back.

Thus far though, that anecdotal feedback hasn’t translated into a material rise in the overall wage data (in Canada or the US).

In its latest policy statement, the BoC observed that “considerable [employment] slack remains, and some groups are still being disproportionately affected – particularly low-wage workers” and that “wage increases have been moderate to date”.

- Inflation expectations remain well anchored.

If consumers become increasingly worried about rising inflationary pressures, they may accelerate their purchase plans to avoid having to pay higher prices in the future. And if enough of them do that, price rises will become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

But our consumer surveys are not indicating that to be the case, and the BoC recently assessed that “medium-term inflation expectations remain well-anchored”.

By and large, consumers agree with the Bank’s assessment that current price spikes will prove transitory (as some already have).

- Demand destruction is reducing inflationary pressures.

When our lockdowns ended, surging demand outpaced supply, and that put upward pressure on some prices. But some of that demand has since shifted to cheaper alternatives as a result.

To wit, on a recent walk I noted a house under renovation that was being framed with metal studs instead of wood (and I don’t remember seeing that before).

As the saying goes, the cure for high prices is, high prices.

- The pandemic is still in the middle innings.

Anyone still hoping that a Roaring Twenties recovery is imminent needs to go back to the drawing board.

The delta variant is surging in Western Canada, and Alberta, which was the first to ease restrictions earlier this year, has just declared a state of emergency.

In Ontario, schools have been back in session for only a few weeks, and there have already been concerning outbreaks to the point where it now seems unlikely that in-class learning will continue for much longer.

If we go back into lockdown, the surging demand for high-contact services will disappear overnight.

- Our economic momentum is stalling out.

Our economy was expected to rebound quickly after the third-wave lockdowns were lifted, as it had in earlier stages. But that narrative was knocked for a loop when we learned that our GDP shrank by 1.1% in the second quarter.

The primary causes were a 12% decline in our real-estate sector, which had been the primary driver of our momentum for a long time, and a 12% drop in export sales, which the BoC expects to be the key driver of our recovery.

It’s hard to imagine surging demand holding up for long against that backdrop.

- Stagflation is a risk, but not an immediate one.

There is a lot of focus now on the risk of stagflation, which happens when high inflation occurs alongside stagnant economic conditions.

The last time we saw stagflation was in the 1970s when inflation peaked at more than 14% and interest rates rose above 20%, and the people who lived through that period are quick to remind everyone else about it today.

Stagflation could certainly emerge in the future, but if it does, it will be caused by different factors this time around.

Inflation took off in the 1970s for many reasons, including the Vietnam war, spiking oil prices and surging demand from up-and-coming baby boomers. But a large part of that inflation spike was also attributed to cost-of-living-adjustment (COLA) clauses in union contracts, which increased wages alongside rising prices automatically and triggered a self-reinforcing wage-price spiral.

Persistently rising labour costs could certainly create a stagflation scenario going forward, but (as per #4) the current data don’t point to this as a material risk. Also, COLA clauses are much less prevalent today, so a surge in wage costs would need a different catalyst this time around.

- Long-term deflationary factors haven’t gone away

There are long-term deflationary forces that will still be at work long after the pandemic is behind us.

For example, debt is deflationary. It soaks up resources, chokes off growth, and holds down the rate at which money circulates through the economy (referred to as the velocity of money). Today, debt’s impact is magnified by the fact that households and governments have more of it than ever before.

Technological advances are also reducing costs, most prominently, the need for labour. The pandemic accelerated this trend as businesses clamoured to replace labour lost to lockdowns.

Aging baby boomers are also having a long-term deflationary impact because older people tend to spend less.

Now back to the key question for readers of this blog: What does my inflation outlook mean for Canadian mortgage rates?

Before I answer that, let me offer what may seem like a surprising concession.

I think the only way today’s massive debt levels will ever be resolved is through inflation.

We can’t possibly pay it all back, and outright default would be too destabilizing, so, ultimately, our system will inflate it away.

The key is when.

If you think ultra-low rates and massive amounts of quantitative easing combined with government largesse are enough to do the trick, consider that Japan has been a poster child for all three measures for more than three decades now, and its inflation has stayed well below 2% over almost all of that period.

My focus is on what will happen over the next five years, and more specifically, whether fixed or variable mortgage rates will likely outperform.

I continue to believe that the BoC will tolerate our current inflation run-up because even if it lasts longer than expected, the Bank remains steadfast in its belief that it will prove transitory.

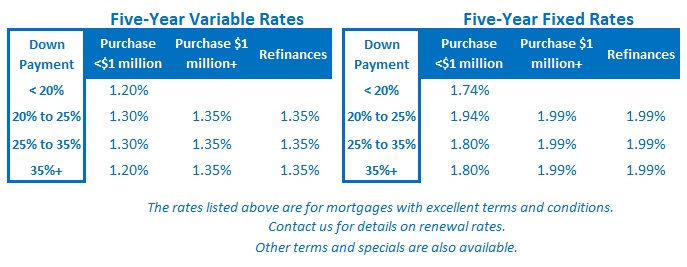

But I also believe that our recovery will take longer to unfold than the BoC’s expected timeline. If I’m right, its next rate rise will take longer than the second half of next year to materialize, and give variable-rate borrowers more time to accrue savings over the available fixed-rate alternatives. The Bottom Line: Lenders dropped their five-year fixed rates last week, as I had previously expected.

The Bottom Line: Lenders dropped their five-year fixed rates last week, as I had previously expected.

The five-year GoC bond yield they are priced on moved higher last week, but not to a degree that would reverse the current trend of flat or falling fixed rates.

Variable rates held steady last week, and based on my viewpoint outlined above, I don’t think they will rise until some time after the BoC’s currently forecasted timeline of the second half of 2022.