How Canadian Mortgage Rates Are Benefiting from Our Current “Inflationary Sweet Spot”

November 20, 2017The Inconvenient Truth About Our Latest Employment Report

December 4, 2017 On January 1, 2018, our regulators will implement a sixth round of mortgage rule changes as part of their ongoing attempts to slow our economy’s rate of mortgage debt accumulation. While I agree in principle with their instincts and with their earlier changes, I take issue with their most recent methodology.

On January 1, 2018, our regulators will implement a sixth round of mortgage rule changes as part of their ongoing attempts to slow our economy’s rate of mortgage debt accumulation. While I agree in principle with their instincts and with their earlier changes, I take issue with their most recent methodology.

For example, in a recent post I criticized the decision to use an average of the posted rates at the Big Six Banks to set the stress-test rate, because posted rates aren’t actually used for lending and because relying on rates from a sub-group of lenders effectively means that the regulator is delegating de facto control over consumer access to mainstream borrowing. I also questioned whether 4.99% was the right rate to use and called on our regulators to provide a more thorough rationale for their approach, basically arguing that the stress test should also be subject to a smell test, especially given its increased importance as a key Canadian benchmark rate.

While I think a deeper explanation is warranted in both cases, more pressingly, there are two specific aspects of the upcoming changes that are fundamentally flawed and need to be addressed prior to January 1.

Flawed Change #1: The New Stress Test for Uninsured Borrowers

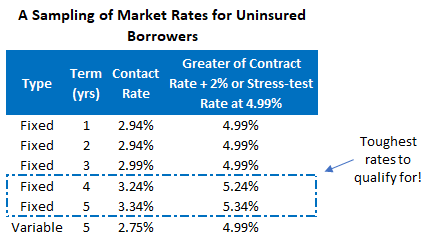

As of January 1, 2018, uninsured borrowers will have to qualify at the greater of the stress-test rate (which is 4.99% today) or their contract rate plus 2%.

When the decision was made to start stress testing uninsured borrowers, the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) initially wanted them to qualify at their contract rate plus 2%. But they realized that this would steer borrowers towards shorter fixed-rate terms or variable rates because these rates were lower (and thus easier to qualify for).

To ensure that its new rule didn’t force uninsured borrowers to have to renew their rates more frequently, OSFI added a tweak that requires them to qualify at the greater of the contract rate plus 2% or the current stress-test rate.

While this tweak narrowed the gap between the rates used to qualify shorter-term and longer-term borrowers, it didn’t eliminate it. For example, today uninsured five-year fixed rates are higher than 2.99% and shorter-term fixed rates are lower than 2.99%. (See chart below.) As such, the new stress test for uninsured borrowers still makes it easier for stretched borrowers to qualify for a shorter-term fixed rate or a variable rate, even though choosing these options raises their overall interest-rate risk (and is clearly not what OSFI intended).

The simple way to eliminate any gap between the term and type of mortgage borrowers can qualify for is to have everyone qualify at the same stress-test rate (and this is already the standard that is applied to all high-ratio borrowers today).

This change is easy to implement; it makes all borrowers indifferent to any term and type of mortgage from a qualification standpoint; and it simplifies the process for lenders in the bargain.

Flawed Change #2: Requiring Renewing Borrowers to Pass the Stress Test If They Want to Switch Lenders

Borrowers who renew with their existing lender will not have to qualify under the new stress test, but those who want to switch lenders will be subject to the new rules. Why?

From a risk standpoint, this makes no sense.

The risk attached to borrowers who renew their existing mortgage without making any changes is completely unaffected by whether they stay with their existing lender or switch to a new one.

In fact, denying some renewers the option to shop for the best deal likely forces them to pay a higher rate once their existing lender realizes that they have them over a barrel. As such, this rule change will reduce affordability for stretched borrowers and adds risk to our financial system over time (which is, quite surprisingly, the opposite of what OSFI intended).

Unfortunately, OSFI is not known for its willingness to respond to feedback, no matter how compelling. Regrettably, it may wait to see market-based evidence of a shift toward floating rate or shorter-term fixed-rate mortgages, or evidence of borrowers who renewed at higher-than-market rates because they had no other choice. That said, public pressure may build as the new rule changes begin to bite. As that happens, perhaps OSFI’s political masters will compel it to address the two fundamental flaws outlined above.

Over the longer term, I hope that OSFI will consult with market participants before, rather than after changes are announced (and not just with the Big Six banks). Consultation works well in other industries and as the flaws outlined above show, it could make a big difference in ours as well.

The Bottom Line: While I agree with our regulators’ instincts and with their earlier moves to slow our rate of household debt accumulation, I have concerns about specific aspects of the next round of mortgage rule changes. Specifically, today’s post has outlined two obvious and fundamental flaws in the new rules that will take effect on January 1, and here’s hoping that OSFI fixes both while it still has time.