The Bank of Canada (Surprisingly) Opts for Caution

July 15, 2019Will Lenders Someday Be Paying Us to Take Out A Mortgage? (Don’t Wish For It)

July 29, 2019 Last week the Bank of Canada (BoC) lowered its Mortgage Qualifying Rate (MQR) from 5.34% to 5.19%, marking the first MQR decrease since September 2016.

Last week the Bank of Canada (BoC) lowered its Mortgage Qualifying Rate (MQR) from 5.34% to 5.19%, marking the first MQR decrease since September 2016.

In today’s post I’ll offer a quick review of how the MQR works before highlighting some fundamental and persistent design flaws in this critically important benchmark.

Let’s start with a basic explanation of how the MQR is used during the mortgage qualification process:

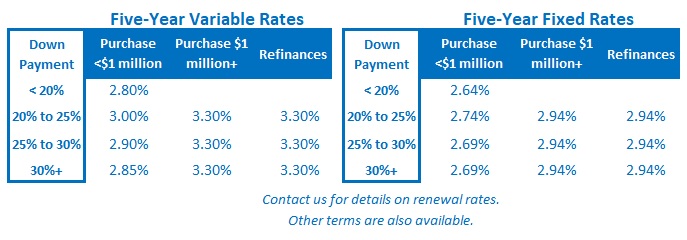

- If you’re in the market for a five-year fixed-rate mortgage today, you’re looking at rates a little below 3%, and if you’re looking for a comparable five-year variable-rate today, those rates are typically about 0.20% to 0.35% higher (a sign of the strange times in which we live).

- Even though the rate on your five-year mortgage is likely to be a little above or below 3%, lenders will use the MQR rate (now 5.19%) to qualify you for the amount you want to borrow. This “stress test”, as it is commonly called, is designed to ensure that you can afford to renew your mortgage at higher rates down the road.

- If you are putting down less than 20% of the purchase price of a property, you are always qualified using the MQR.

- If you are putting down more than 20% of the purchase price of a property, or refinancing/renewing your existing mortgage, your application will be qualified using the greater of the MQR, or the rate on your mortgage plus 2%. (Since most of today’s rates are lower than 3.19%, the vast majority of these borrowers are also now being qualified at the MQR).

The MQR drop of 0.15% only adds a few thousand dollars of purchasing power to each borrower’s bottom line, so that news alone doesn’t warrant much ink. But with the MQR back in the headlines, now seems like a good time to take another look at its fundamental design flaws, none of which have been addressed by our policy makers since its introduction.

Before I step onto my soapbox, let me reiterate my support for all of the mortgage rule changes that have been enacted since the financial crisis, including the introduction of the MQR stress test. Bluntly put, our policy makers needed to intervene to reduce our rate of debt accumulation and to slow the acceleration of house prices in many of our regional housing markets. That said, while they have done a mostly admirable job with the rule changes and while the MQR is sound in principle, its design remains fundamentally flawed.

Here are several reasons why I say that:

- Methodology: The MQR is calculated by taking the mode of the five-year posted mortgage rates at the Big Six banks. But the Big Six don’t actually lend at these rates. They are primarily used to inflate the penalties that fixed-rate mortgage borrowers pay when they break their Big Six bank mortgages before the end of their term (as I detail here). So the current method for calculating the MQR is essentially based on arbitrarily set non-market rates that earn the banks that set them more profit when they are kept high.

- Inconsistency: For anyone needing further proof that the MQR moves without rhyme or reason, consider that on July 1, 2017 when the Government of Canada (GoC) five-year bond yield closed at 1.42%, the MQR stood at 4.64%. Today, the GoC five-year bond yield is back at 1.42% but the MQR has only just been lowered from 5.34% to 5.19%. Glaring inconsistencies like this would be eliminated if the MQR were priced on real market data.

- Transparency: Without a clear understanding of how (and why) the MQR is set, any meaningful debate among market participants about the appropriate MQR level is impossible. Increased transparency would open up discussion about how factors such as amortization of principal, average incomes, total consumer debt, and rate forecasts are likely to impact renewal rate risk. (I touch on that point in my recent BNN Bloomberg interview.)

- Efficacy: The stress test makes it harder for borrowers who are putting down more than 20% of the purchase of a property, or who are refinancing/renewing, to take on longer term mortgages. While most of today’s five-year rates plus 2% come to less than the current MQR rate of 5.19%, when you add 2% to today’s seven- and ten-year fixed rates, they come in higher. This means it is tougher to qualify for longer-term mortgages, even though they better protect borrowers from the very renewal rate risk that the stress test was designed to mitigate.

- Fairness: Right now, the only situation where the stress test isn’t applied to mortgage applications at federally regulated lenders is when borrowers renew with their current lender. If they find a better offer elsewhere and want to switch to a different lender, they have to pass the stress test. This effectively traps the borrowers who would most benefit from securing a lower rate at renewal. Worse still, lenders can often identify these borrowers, and to no one’s surprise, can inflate the renewal rates offered to them. (For anyone keeping score at home, the Big Six banks have the largest loan books, by far, so they stand to benefit the most from this incumbent-favouring rule. The results of effective lobbying by the Big Six banks are seldom so obvious, and I would have thought that our regulators would have felt embarrassed enough to have addressed this unfairness by now.)

[Steps down from soapbox.] The Bottom Line: Last week the MQR fell from 5.34% to 5.19%. While this drop increased every mortgage borrower’s affordability by a few thousand dollars, it won’t have much market impact. The changes I call for above would have much more impact, and they are long overdue. Here’s hoping that shining more light on the MQR’s flaws helps to hasten the improvement of this important regulatory tool.

The Bottom Line: Last week the MQR fell from 5.34% to 5.19%. While this drop increased every mortgage borrower’s affordability by a few thousand dollars, it won’t have much market impact. The changes I call for above would have much more impact, and they are long overdue. Here’s hoping that shining more light on the MQR’s flaws helps to hasten the improvement of this important regulatory tool.

1 Comment

thanks for sharing this.