The Bank of Canada Can’t Ignore the Lofty Loonie for Much Longer

November 18, 2019Our Latest GDP Data Aren’t Likely to Alter the Bank of Canada’s Outlook

December 2, 2019 Last Wednesday, Statistics Canada confirmed that our overall inflation rose by 1.9% on a year-over-year basis in October, consistent with the consensus forecast.

Last Wednesday, Statistics Canada confirmed that our overall inflation rose by 1.9% on a year-over-year basis in October, consistent with the consensus forecast.

The Bank of Canada (BoC) also closely monitors three other measures of core inflation (CPI-trim, CPI-median and CPI-common) and these were also essentially unchanged for the month. All three still hover very close to the Bank’s 2% target.

On the same day, BoC Governor Stephen Poloz spoke at the Ontario Securities Commission and said that “we think we’ve got monetary conditions about right given the situation”, citing strength in housing and services and noting that inflation is currently on target.

If he’s referring to the current situation, no argument here, but after listening to the Bank repeat over and over that it must anticipate the road ahead, especially given that inflation itself is a lagging indicator, I think its stand-pat approach could prove costly in the fullness of time.

To quickly recap, the BoC is mandated to promote the well-being of Canadians “by keeping inflation low, stable and predictable.” It does this by using its monetary policy to keep our Consumer Price Index (CPI) as close as possible to its target rate of 2%, and more broadly, within a range of 1% to 3%.

Everyone focuses on the Bank’s 2% target, but the operating range is also important. It gives the Bank leeway to let inflation run a little hot or cold if it’s in the best long-term interest of our economy. Here are several reasons why I think now should be one of those times:

- The BoC has long argued that any lasting recovery must be led by rises in business investment and export sales. That just hasn’t happened. Our export sales have fallen for four months in a row on a year-over-year basis, and the (relatively) lofty Loonie hasn’t helped. Meanwhile, non-residential capital investment has seen its worst three years of growth since 1961. A lower policy rate would weaken the Loonie, and in so doing boost our exports, and that combination might also at long last spur a sustainable uptick in business investment.

- Our current momentum is being led, in part, by a housing rebound, and the Bank is no doubt concerned that rate cuts could overheat real-estate markets and cause household borrowing to accelerate. But today’s borrowers are qualified using the stress test rate, which doesn’t have any discernable correlation with the BoC’s policy rate, as I explain in detail in this post. (For its part, the Bank hasn’t cut its policy rate since the stress test was introduced and says that it isn’t entirely sure how powerful a mitigant the test will be. I think it’s time to find out.)

- Last week we learned that our GDP growth slowed to 2.0% in the third quarter on an annualized basis, down from 2.9% in the second quarter. This slowdown was largely expected, but our economy actually contracted by 0.1% in September on a month-over-month basis, and that doesn’t bode well for our momentum heading into the fourth quarter (otherwise known as the road ahead).

- Strangely, Governor Poloz’s “about right” comment came only a day after BoC Deputy Governor Carolyn Wilkins gave a speech talking about the “immense challenges” facing the global economy” and of “increased risks to the global expansion” amid a long list of uncertainties and potential trouble spots. Despite this, Wilkins reiterated the Bank’s belief that “taking out insurance [in the form of a rate cut] wasn’t worth it” at the BoC’s last meeting. That stands in stark contrast to the actions of most of the world’s other central banks, which have collectively dropped their policy rates by 2,200 basis points (and counting) thus far in 2019.

- The BoC estimates that it can take anywhere from 18 to 24 months for rate changes to exert their full impact. That means that the five rate hikes the Bank enacted between July 2017 and Oct 2019 are still exerting a tightening impact on our already waning economic momentum and will continue to do so well into 2020, which I explain in more detail here.

The consensus doesn’t expect the BoC to drop its policy rate at its next meeting, on December 4, and the Bank’s recent commentary supports that view. But if the BoC waits for inflation to show discernable signs of slowing before cutting, it runs the risk that it will then have to lower by more to produce the same stimulative effect.

Relying too much on a lagging indicator can leave you well behind the curve.

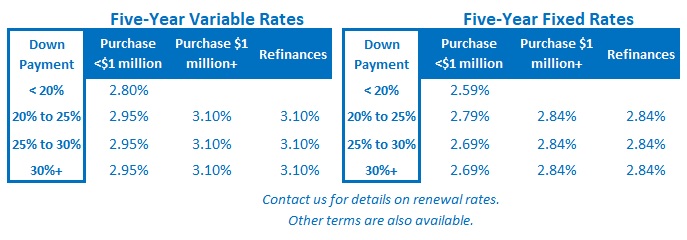

The Bottom Line: The BoC isn’t expected to cut its policy rate when it next meets on December 4. While that means variable mortgage rates aren’t likely heading lower in the near future, I think there are clear signs of slowing both at home and abroad, which will eventually force the Bank’s hand. Further, if the BoC waits too long, it may have to cut its policy rate to a greater extent to get out in front of slowing momentum. Fixed mortgage rates are holding steady, as the Government of Canada bond yields they are priced on fluctuate within a fairly tight range.