Canadian Mortgage Rate Forecast (2019): Look Out Below

January 7, 2019All Quiet on the Canadian Mortgage-Rate Front (for Now)

January 21, 2019 The Bank of Canada (BoC) left its overnight rate unchanged last week, as expected, and that means Canadian variable-rate mortgages will remain at their current levels for the time being.

The Bank of Canada (BoC) left its overnight rate unchanged last week, as expected, and that means Canadian variable-rate mortgages will remain at their current levels for the time being.

The Bank also released its latest Monetary Policy Report (MPR), which provides a detailed analysis of where it sees both foreign and domestic economic growth and inflation headed over the next two years.

The latest MPR is of particular interest to market watchers because it is the first one issued since the BoC shifted from hawkish to dovish policy-rate language in December (its previous MPR was released last October).

In summary, the Bank expects our current slowdown to continue through the first half of 2019 before our economy resumes its previous growth trajectory. Its latest forecast is based on the assumption that our economic momentum will be supported by “strong employment, expanding foreign demand and accommodative financial conditions”. In my view, there was a glaring omission in the Bank’s analysis, but before I get to that, let’s start with a quick summary of the highlights from the latest MPR.

The BoC expects a “material moderation” in global economic growth in 2019, and it is forecasting a slowdown in global GDP growth from 3.7% in 2018 to 3.4% in both 2019 and 2020. The Bank noted “important uncertainties” for the global economy in the year ahead and highlighted the U.S./China trade dispute and Brexit as its primary concerns.

Not surprisingly, the recent decline in global oil prices dominated the BoC’s rationale for its more dovish domestic outlook.

It noted “considerable uncertainty around the future path for global oil prices”, which have fallen by about 25% cent since last October, largely as a result of increased U.S. shale production. That uncertainty is underpinned by investor concerns that “trade and geopolitical risks could weigh on demand”.

Canadian oil prices have been further impacted by “transportation constraints and rising production”. The BoC acknowledged that the price differential between Canadian and global oil prices has recently narrowed (from more than $50 in late October to about $9 today) after the Alberta government announced mandatory production cuts, but it still predicted that investment in our oil sector would “weaken further”.

The Bank attributed the slowdown in Canadian GDP in the fourth quarter primarily to the oil-price drop, but interestingly, it estimated that the economic impact will only be “about one-quarter the size” of the impact from the oil-price shock we experienced in 2014-2016. That’s because “oil prices have fallen by less than in 2014 [even though prices are lower now than they were then], and oil production represents a smaller nominal share of the Canadian economy today [because the sector hasn’t fully recovered from the previous shock]”. To wit, oil and gas production accounted for 6% of our nominal GDP in 2014, and that number fell to 3.5% in 2018.

The BoC observed a significant divergence in economic data between our oil-producing and non-oil-producing provinces. For example, it attributed the recent steady drop in our average wage growth to our oil-producing regions and noted that elsewhere, wage growth has remained steady since the start of 2017. The Bank cited a similar dichotomy in business investment, household spending, fiscal revenues, and on inputs to our consumer price index (CPI).

Despite strong headwinds from trade uncertainty, geopolitical risks, and sharply lower oil prices, the BoC assessed that the “Canadian economy has been performing well overall” thanks to “strong” employment growth, unemployment “at a 40-year low” and the economy “running close to potential”. The Bank’s positive overall assessment was in spite of “weaker than expected” consumer spending and weakness in our regional housing markets, which are “taking longer to stabilize than we expected”.

The BoC revised its forecast for our GDP growth in 2019 down from 2.1% to 1.7% but predicted that we would see signs of “renewed momentum in early 2019, leading to above potential growth of 2.1% in 2020”. It also projected that inflation will remain below its 2% target level “through much of 2019” before returning to target by the end of the year.

In its closing statement, the Bank continued to predict that it would need to raise its policy rate “over time into a neutral rate range to achieve the inflation target”, with the appropriate pace determined by “developments in the oil market, the Canadian housing market, and global trade policy”.

Now for the glaring hole in its forecast.

The BoC outlined a litany of uncertainties that could impact its projections over the next two years. Upside risks included stronger-than-expected Canadian business investments and exports, and stronger real GDP growth in the U.S. Downside risks centred on a sudden tightening in global financial conditions and sharp house-price declines in certain Canada regions. The Bank also noted that some risks had both upside and downside potential, such as trade conflicts and oil-price movements.

While the BoC’s list of potential risks was extensive, I believe it missed the most significant one: the risk that the lagged impact from the five quarter-point rate hikes it has made since July 2017 will kill what remains of our hard-won economic momentum. (The BoC’s latest forecast is actually based on the assumption that “domestic demand should pick up” in the first quarter of 2019.)

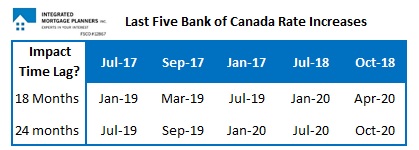

In his accompanying press conference, BoC Governor Poloz reiterated the need for the Bank to anticipate the road ahead and repeated his previous estimate that it can take between 18 and 24 months before the full economic impact of each rate hike can be felt. (He then used the analogy of a hockey player having to pass the puck ahead of their onrushing teammate to ensure that it hits them in stride.)

That’s concerning because our already slowing economy is only just now experiencing the impact from the first of the BoC’s five previous rate hikes (see chart below).

Note that it has now been only eighteen months since the Bank first raised its policy rate in July 2017. That means that our already slowing economic momentum has a new and powerful headwind that is about to assert itself. Given that economic recessions have historically been preceded by monetary-policy tightening, I see the lagged impact of the BoC’s five recent rate hikes as the biggest single risk for our economic momentum over the next two years.

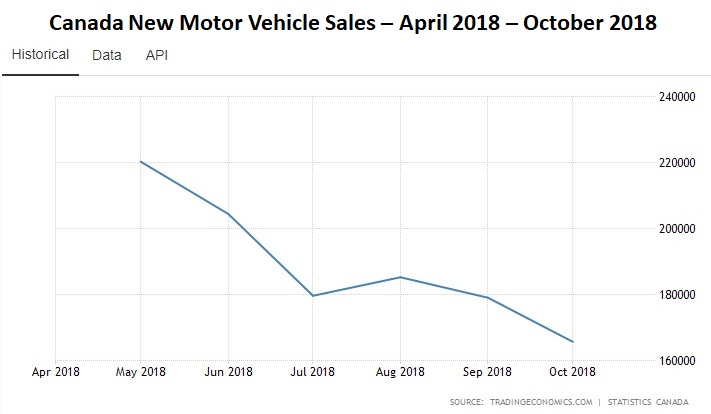

The Bank seems far less concerned. While it did speculate that the economy “may be more sensitive” to higher interest rates than previously estimated, monetary-policy over-tightening didn’t rate a mention in the Bank’s top seven risks listed at the end of its latest MPR. That is despite the BoC’s acknowledgement that housing activity has already been “weaker than expected” and notwithstanding the fact that Canadian auto sales, which are highly sensitive to interest-rate rises, have already declined sharply (see chart).

As a long-time hockey coach, I will extend Governor Poloz’s hockey analogy a little further. While we teach our players to lead their teammate with a pass, we also teach them to pay attention to what’s coming in the other direction. If you make your pass without accounting for that, your teammate could be flattened by the opposition just as the puck to arrives. We refer to that as a hospital pass, and here’s hoping that the BoC’s five recent rate hikes don’t fall into that category as our already weakening economy absorbs the full impact of previous rises in 2019 and 2020.

The Bottom Line: The BoC held its policy rate steady last week as expected. In its accompanying MPR, the Bank estimated that our current slowdown will dissipate during the first half of this year and that our economy will resume its previous trajectory thereafter.

While I hope the BoC is proven correct, I am concerned that the lagged impact of the five recent rate increases will compound the recent slowdown. This is not the first time I have disagreed with aspects of the BoC’s forecasts, and I want to make it clear that I do not do so lightly. Time, as always, will be an impartial referee.

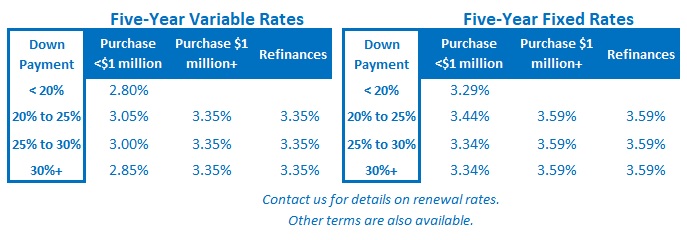

For now, our variable mortgage rates remain unchanged, and there is continued downward pressure on our fixed mortgage rates as their foundational Government of Canada bond yields continue to fall.