Fixed or Variable Mortgage Rate – Which One Should You Choose?

March 8, 2021Central Bank vs. the Bond Market: Round 2

March 22, 2021The five-year Government of Canada (GoC) bond yield that our five-year fixed mortgage rates are priced on has moved steadily higher of late in response to the consensus belief that inflation has turned the corner and will now rise sustainably.

It increased from 0.40% to 1.04% over the past month, and, not surprisingly, five-year fixed mortgage rates have risen by almost the same amount.

Today’s consensus inflation narrative is underpinned by improving US vaccination rates, the approval of new massive US stimulus programs, and better-than-expected economic data on both sides of the border. These factors are fueling the belief that growth is about to take off, and that, by association, inflation, and rates, have bottomed.

In the lead-up to the latest Bank of Canada (BoC) meeting, which took place last Wednesday, mainstream economists predicted that the improving backdrop would force it to adopt more hawkish language. Specifically, they expected the Bank to hint that it would soon begin to taper its quantitative easing (QE) programs, and to move up the expected timing of its next policy-rate increase.

The BoC had other plans.

It has been saying for some time now that it doesn’t expect to raise its policy rate, which our variable mortgage rates are priced on, until sometime in 2023. It has also used QE to purchase at least $4 billion worth of bonds each week in an effort to, in part, suppress the bond yields that our fixed-mortgage rates are priced on. (The BoC will begin tapering its QE purchases well before it starts raising its policy rate – and that is one of many reasons why fixed mortgage rates are rising well ahead of variable mortgage rates.)

Instead of responding as the consensus expected, the BoC reiterated its commitment to providing extraordinary monetary-policy support to our economy until the recovery is well underway. It did not hint at any QE tapering plans or alter its expected rate-hike timetable.

The BoC (and their counterparts at the US Federal Reserve) now fundamentally disagree with the bond-market consensus about what lies ahead – as I explained in my BNN Bloomberg interview last Wednesday morning, immediately after the BoC issued its latest policy statement.

Here are some examples of where they don’t see eye to eye:

- The BoC noted that the global economic momentum is recovering, but with “ongoing unevenness across regions and sectors”. Conversely, the bond market is pricing a full steam ahead rebound and believes that we are on the precipice of an economic recovery similar to the one experienced in the Roaring Twenties after the Spanish flu pandemic ended.

- The BoC acknowledged that “there is still considerable economic slack and a great deal of uncertainty about the evolution of the virus and the path of economic growth”, and more importantly, it raised concern that “the spread of more transmissible variants of the virus poses the largest downside risk”. In contrast, the consensus has now completely discounted the risks of a third wave and more lockdowns, despite the fact that the medical community continues to warn about this possible, and even probable

- The Bank predicts that our inflation data will “move temporarily to around the top of the [1% to 3%] band in the next few months” as depressed prices from a year ago roll out of the CPI calculations and are replaced by today’s more normalized prices, but it expects inflation to moderate thereafter. The consensus believes that inflationary pressures will continue to build.

- The BoC reiterated its belief that our recovery will continue “to require extraordinary monetary policy support” and reaffirmed its belief that overall inflation will not sustainably return to its 2% target “until into 2023”. The consensus thinks the Bank should be reducing its QE purchases and raising its policy rate before then.

The BoC’s statement wasn’t accompanied by detailed analysis this time around. It has ten policy-rate meetings each year, but only four of them include the Bank’s quarterly Monetary Policy Report (MPR), which provides its detailed assessment of current conditions. (FYI – the next MPR will be issued at the BoC’s April 21 meeting.)

The BoC compensated somewhat for its short-and-sweet policy statement by having its Deputy Governor, Lawrence Schembri, give a speech the next day (Thursday) to shed more light on its current thinking.

Here were some of his key themes:

The BoC Is Still Highly Uncertain About the Pandemic’s Path – Schembri said the Bank was paying close attention to the risks “of another wave of infections and lockdowns as more contagious variants spread, the rollout of the vaccines is delayed, or the vaccines are less effective against the variants.” Interestingly, in its January MPR the BoC based its more optimistic outlook on the assumption that our federal government would meet its promise of vaccinating every willing Canadian by September. That timeline now seems wildly optimistic, so I’m not surprised to see the Bank make direct reference to the federal government’s overestimate.

The BoC Isn’t Convinced the Roaring Twenties Await – Schembri noted that while the pandemic has led Canadians to accrue “forced” and “precautionary” savings, which now total an estimated $180 billion, he also warned those who are anticipating the sudden release of those savings that “this positive surprise is not guaranteed”. He explained that some of that saving has been used to pay down debt, while some has also likely been tied up in investments. He also highlighted a recent BoC survey of consumers wherein “only 5 percent of respondents said they plan on spending most of these savings in 2021 and 2022. Another 14 percent plan on spending some”.

The BoC Remains Concerned About the Health of Our Labour Market – Schembri noted that our economy has experienced “about twice as many job losses as there were at the height of the Great Recession a decade ago”. He also highlighted the “uneven impacts of job losses” and the continued rise of long-term unemployment as a key risk, because it “erode[s] workers’ skills and make[s] it more difficult for them to find a job”.

The BoC Still Expects the Recovery to Take a Long Time – Schembri explained that over the medium term, “we could see more firms close as the recovery progresses slowly … businesses may face increasing financial stress … [and] more businesses could permanently shut their doors and let employees go.” Meanwhile, “establishing new post-pandemic businesses, and retraining workers to support them will take time”. He also reiterated the Bank’s expectation that “monetary policy stimulus will be needed for an extended period to mitigate these risks and support both the restructuring and recovery of our economy.”

The BoC Didn’t Sound as Concerned About House Prices as Many Thought It Should – Some thought the Bank should have started warning about the risk of outright price bubbles. Schembri noted that housing activity has been “particularly strong” and that “large house price increases in some markets will warrant close monitoring for speculative activity” but stopped short of saying the B word. I suspect that’s because the BoC will take whatever sources of economic momentum we can get at this point, and that it also draws comfort knowing that the vast majority of mortgage borrowers are being qualified using the stress-test rate, which at 4.79% is more than double the real rates that people are actually borrowing at.

So, what does this evolving backdrop mean for mortgage rates?

If the bond market was worried about rising inflation before last week’s BoC meeting, it will be even more so now that the Bank has whole-heartedly maintained its ultra-accommodative monetary policies. This key disconnect between the bond market and the BoC may cause investors to push our bond yields and our fixed mortgage rates higher over the short term.

Conversely, the BoC has just reassured variable-rate borrowers that it has no plans to move up the timing of its next rate hike, which means our variable rates still aren’t likely to rise until sometime in 2023.

For my part, I continue to subscribe to the (minority) view that our impending inflation run-up will prove transitory, that our flagging vaccination rates in Canada significantly increase the risk of a third wave, and that most of the surplus cash currently parked on household balance sheets will remain there for a long time yet.

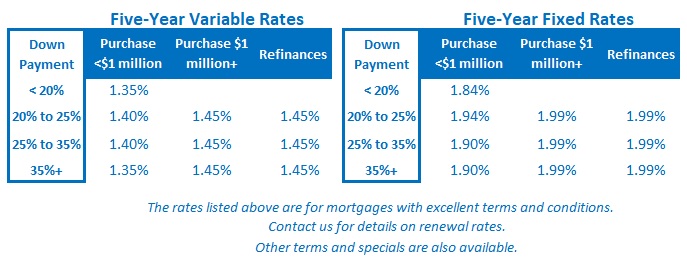

Simply put, I still think today’s five-year variable rates will outperform their fixed-rate equivalents (as my post from last week explains in detail). The Bottom Line: Five-year fixed rates continued to move higher last week while five-year variable rates held steady. That has caused the gap between fixed and variable rates to widen to a level not seen since late 2018.

The Bottom Line: Five-year fixed rates continued to move higher last week while five-year variable rates held steady. That has caused the gap between fixed and variable rates to widen to a level not seen since late 2018.

The disconnect between the bond market and the BoC may continue to push fixed mortgage rates higher over the near term, while the BoC’s steadfast plan to hold its policy rate steady until 2023 means that variable rate rises are still likely to be a long way off.