Fixed vs Variable: Which One Is Now the Better Bet?

April 25, 2022Five Thoughts on Last Week’s Mortgage-Related News

May 9, 2022Canadian mortgage rates have been on a tear lately.

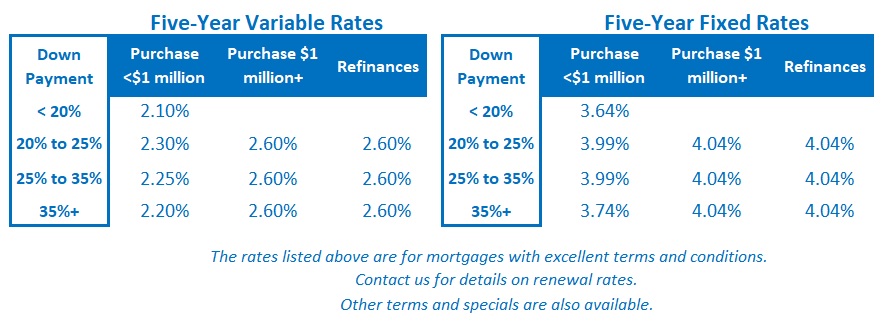

The five-year Government of Canada (GoC) bond yield has more than doubled, from 1.25% in early January to 2.78% at last Friday’s close, and that has driven our five-year fixed mortgage rates up into the 4% range, marking their highest level in more than a decade.

Meanwhile, the Bank of Canada (BoC) has hiked its policy rate by a total of 0.75% over its last two meetings, and lender prime rates, and the variable mortgage rates that are priced on them, have increased by the same amount.

Those developments may have been big news on the home front, but they are mere sidenotes on the global stage. The biggest punch bowl at the global cheap-money party belongs to the US Federal Reserve, and the Fed is expected to start taking that punch bowl away when it meets this week.

US inflation has climbed steadily higher over the past six months, hitting 8.5% in March, and financial markets are pricing in an aggressive Fed response. The Treasury-bond futures market expects 2.25% in Fed hikes over the remainder of 2022, and Quantitative Tightening (QT) is being priced into bond yields as well.

Under QT, the Fed will allow the $3.3 trillion in Treasuries and the $1.3 trillion in mortgage-backed securities that it purchased through its Quantitative Easing (QE) programs during the pandemic to roll off its balance sheet when they come up for renewal. (Over the near-term, $326 billion of that debt is in short-term Treasury bills.) This will increase the supply of US bonds in the secondary market, causing their yields, and the borrowing rates associated with them, to rise further.

All of this may lead my readers to imagine that our GoC bond yields, which generally move in near lockstep with their US equivalents, are about to also head higher, but I’m not convinced that will be the case.

For starters, financial markets tend to buy the rumour and sell the fact, so even if the Fed enacts a hawkish hike this week, which I would define as a 0.50% hike and strong language about an aggressive tightening path going forward, bond-market investors have pretty much priced all of that in.

But that’s not what I expect will happen.

While the Fed will almost certainly hike by 0.50% and use strongly worded language about getting inflation back under control, I think it will also have to acknowledge that its pace for future rate hikes and QT will be dependent on the evolving US economy, which has weakened of late.

The Fed will use monetary policy to reduce demand until it meets supply at its currently impaired levels, but rate hikes and QT aren’t the only forces that are now conspiring to achieve that end.

Here are some other factors that are doing some of the heavy lifting for demand destruction:

- The US federal government recently ended the pandemic-related emergency stimulus programs that were super-charging both demand and consumer spending. Fiscal policy was a tailwind in 2021, but it is now a headwind.

- US median wage growth lags well behind US inflation, which means the purchasing power of the average American is still shrinking, and that gap has widened of late. US average hourly earnings increased by only 0.4% from February to March, while the US Consumer Price Index rose by 1.2% over the same period.

- The Fed will be tightening policy at a time when the US economy is already contracting (US GDP fell by 1.4%, annualized, in the first quarter). This is most unusual. Central banks typically tighten when their economies are over-heating, not when they are cooling.

- Frances Donald, Chief Economist at Manulife Financial, also noted that inflationary pressures have evolved over the past two years. While “COVID inflation” was primarily driven by price rises in discretionary items that consumers could forgo, today’s price surges are being driven by “conflict inflation” (resulting from the war in Ukraine), which is driving up the cost of essential goods like food and energy that borrowers can’t do without. That kind of inflation acts like a tax on other forms of spending.

- US consumers are becoming more cautious of late. The prominent Michigan Consumer Sentiment survey fell to its lowest level in more than a decade in March – and decreased sentiment portends decreased spending.

The Fed is in a corner now.

It has to tighten monetary policy to restore some measure of control over the inflation narrative. But Fed Chair Powell has already acknowledged that rate hikes and QT will do nothing to address the main causes of today’s inflationary pressures, which are the war in Ukraine and ongoing Chinese lockdowns.

Instead, the Fed is hoping that rate hikes will reduce demand enough to keep inflationary pressures from broadening to the point where wage costs start to really break out. If that happens, a self-reinforcing wage/price spiral could ensue where higher prices beget higher wages, and higher wages then, in turn, beget still higher prices.

There may, however, be less risk of that spiral than first meets the eye.

Economist David Rosenberg recently noted that corporate America has just “put through four years of price hikes into one … [and] margins in the non-financial business sector expanded to their highest level in 70 years”. He estimates that labour costs “have accounted for less than 10% of the inflation story … [while] half the inflation run-up in the past year has come from fatter profit margins.”

That suggests that many US companies will not have to automatically raise prices further even if their wage costs rise, and they will be even less likely to do so if they see demand falling at the same time.

The Fed also has to manage the market’s perception of recession risk. While they will talk about achieving a “soft landing”, it won’t be lost on financial markets that over the past 14 hiking cycles, 11 resulted in a recession.

If the Fed is perceived to be hidebound to aggressive monetary-policy tightening, that could trigger a significant stock market sell-off as investors price in a drawn out economic downturn. This happened in 2013 when the Fed floated the idea of tapering its massive quantitative easing programs, and financial markets corrected violently in what became known as the “taper tantrum”. In that instance, the Fed beat a hasty retreat and didn’t end up actually tapering until 2017.

So what’s in store for the week ahead?

My best guess is that bond yields will fall in response to a less-hawkish-than-expected Fed announcement that will try to walk a fine line between reassuring Americans that inflation pressures will be contained, and reassuring investors that it won’t have to drive the US economy into a deep recession to achieve that end.  The Bottom Line: The five-year GoC bond yield fell last Monday and Tuesday, but then rose to finish the week about where it started.

The Bottom Line: The five-year GoC bond yield fell last Monday and Tuesday, but then rose to finish the week about where it started.

For the reasons outlined above, I think that the Fed’s policy announcement this Wednesday may end up being the catalyst for a drop in bond yields that will help stabilize our five-year fixed rates.

Five-year variable rates are likely to hold steady for the time being, but if the Fed lays out a less hawkish path for rate hikes and QT, that will also provide less cover for the BoC to maintain a more aggressive pace.

3 Comments

Great comments Dave. I agree with you. Will be an interesting spring/summer.

Have been following you for years – always excellent commentary – thank you.

Thanks Tom.