Thoughts on Inflation (and Its Impact on Mortgage Rates)

September 20, 2021Why Managing Inflation Today Is Such a Sticky Wicket

October 4, 2021Last week the US Federal Reserve indicated that it expects to begin tapering its massive quantitative easing (QE) programs soon. More surprisingly, the Fed also indicated that it expects to fully unwind its QE purchases by the middle of next year.

That is a faster tightening pace than financial markets had anticipated, and investors reacted in typical fashion – by shooting first and asking questions later.

Our Government of Canada (GoC) bond yields surged higher in response, and that may push up our fixed mortgage rates, which are priced on them, over the near term. The Fed also had some comments that will be of interest (pun intended) to variable-rate borrowers.

In today’s post I’ll summarize what the Fed said last week, point out some inconsistencies, and offer my take on how its updated guidance (and taper plans) may impact our mortgage rates going forward.

First a quick refresher.

When the pandemic first hit, the Fed slashed its policy rate to the floor and announced that it would use QE to purchase at least $80 billion US Treasury securities and $40 billion US mortgage-backed securities each month. This created artificial demand for those assets, and in so doing, helped to drive down their yields. That pushed longer-term rates down and lowered borrowing costs for households and businesses.

When the Fed reduces (tapers) its QE purchases, it is withdrawing the extra demand for those bonds. That should cause their yields, and the rates associated with them, to rise in response (and that rise is what bond-market investors were pricing in last week).

There was probably also some latent market anxiety in the lead up to this tapering announcement. That’s because when the Fed announced that it would begin to taper its QE purchases in 2013, after the Great Recession, financial markets tanked in what became known as “the taper tantrum”.

We didn’t end up seeing nearly as much volatility this time around. (Although technically speaking, the Fed didn’t announce that it would start tapering – only that it was likely to do so in the near future, which it is now widely assumed will be at its next meeting in November.)

Here is my take on the Fed’s latest communications:

The Fed took a credibility hit.

At its previous meeting (which I wrote about here) the Fed was adamant that the employment recovery would need to show “substantial further progress” before it would consider tapering.

That was in late August, and here is a summary of the “substantial” progress that has happened since then:

- The US economy added only 235,000 new jobs last month. That number came in way below the consensus forecast of 750,000 and marked the worst result in seven months.

- The US unemployment rate dropped from 5.4% in July to 5.2% in August but remained well above its pre-pandemic level of 3.5%.

- The US participation rate held steady at 61.7%, also well below its pre-pandemic level of 63.4%.

- The US economy is still approximately 8 million jobs shy of its pre-pandemic employment level.

The numbers above would certainly count as progress, but substantial progress?

Those data aren’t the ones I would be relying on to justify a significant policy shift, and doing so puts a dent in the reliability of the Fed’s guidance going forward (or, at the very least, its choice of important adjectives).

Fed rate hikes are likely still a long way off.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell took pains in his accompanying press conference to make clear that rate hikes are still a long way off. Here is what he has to say on that topic:

- Tapering is “not a direct signal” that rate hikes are imminent.

- The Fed will apply “a different and substantially more stringent test” when determining the right time for rate hikes.

- The test for liftoff (Fed slang for its first rate hike) will be “so much higher” than the test used to determine taper timing

Powell also noted that it wouldn’t make sense to raise rates before the Fed had completely ended QE because “as long as you’re buying assets, you’re adding accommodation, and it wouldn’t make any sense to, you know, to then liftoff”.

If the Fed delays its first policy-rate rise until 2023, I think it is unlikely that the Bank of Canada (BoC) will hike before then because it would push the already lofty Loonie higher against the Greenback, and in so doing, hammer our exporters (as I detailed in this post).

Uncertainty reigns.

In its policy statement, the Fed assessed that “indicators of economic activity and employment have continued to strengthen”, yet its median forecast for US GDP growth in 2021 was lowered to 5.9%, well below its 7% projection in June. Its words and numbers simply don’t match.

The Fed’s latest dot-plot chart indicated that half of its members expect US rates to start rising by the end of 2022, but at his press conference, Powell said that “all but one of the participants have us lifting off in 2023”.

At his press conference, Fed Chair Powell also noted that although some of the Fed’s members are projecting “very low unemployment rates” that “suggest a very strong labor market”, “no one knows with any certainty where the economy will be a year from now”.

The Fed’s median forecast for US GDP growth in 2022 was also raised from 3.3% to 3.8%, and for me, that provides further proof of its willingness to err on the high side.

Inflationary pressures should ease next year.

The Fed’s median forecast for inflation was increased from 3.4% to 4.2% in 2021 and raised from 2.1% to 2.2% in 2022.

But the Fed reiterated its willingness to let inflation run above 2% for some time because, until recently, it had been “persistently below this longer-run goal”. It also repeated its view that today’s elevated inflation rate is “largely reflecting transitory factors”.

While rising inflationary pressures have proven stickier than originally expected, Fed Chair Powell assessed that “indicators of longer-term inflation expectations appear broadly consistent with our longer-run inflation goal of 2 percent.”

That’s important because if consumers and businesses expect that today’s inflationary pressures will continue for an extended period, they may accelerate their purchase plans as a result. If inflation concerns manifest into purchasing actions, that could set off a self-reinforcing inflation spiral.

Thus far at least, Powell noted that, based on survey results, “households expect higher inflation in the near-term, but not in the longer-term”.

Now let’s tie all this back to Canadian mortgage rates.

Implications for Canadian fixed-mortgage rates

The Fed’s taper talk pushed GoC bond yields higher, but not high enough (yet) to move the fixed mortgage rates that are priced on them.

When the Fed follows through on its tapering plans, the consequent reduction in demand for US treasuries and mortgage-backed securities may cause their yields to rise again. If that happens, GoC bond yields will almost certainly be taken along for the ride, and at that point, probably by enough to impact our fixed mortgage rates.

But once that event passes, I still subscribe to the view that today’s elevated inflationary pressures will subside, and that the Fed and BoC’s GDP growth forecasts will both be proven overly optimistic when pandemic-related fiscal-stimulus programs are no longer propping up their economies.

If I’m right, even if fixed rates rise in the coming months, they should settle back down after that.

Implications for Canadian variable-mortgage rates

While Fed Chair Powell told markets to expect the Fed to taper soon, he also made it clear that the Fed will use a “substantially more stringent test” for determining when to begin raising its policy rate.

If the Fed keeps its policy rate nailed to the floor, that will make it much harder for the BoC to raise in the second half of next year, as it says it still expects to do.

Long story short, the BoC is counting on an export-led recovery that will be less likely to materialize if it front-runs the Fed and causes the Loonie to soar further against the Greenback (making our exports less competitive).

I continue to believe that the BoC’s next policy-rate hike will occur later than it is currently forecasting, but that doesn’t guarantee easy sailing ahead for variable-rate borrowers.

Their courage will be tested because if fixed mortgage rates start to rise, so too will the rate for their available fixed-rate conversion options (and anyone contemplating a conversion at that time will be looking at higher fixed rates than those available today).

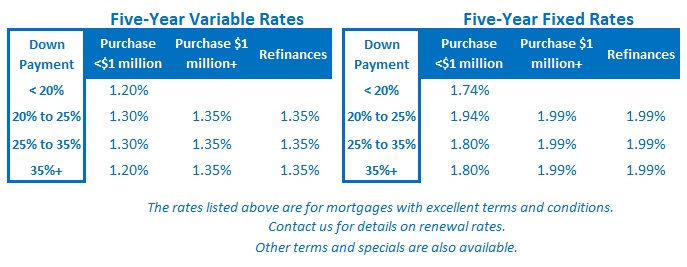

While I continue to believe that variable rates will prove the cheaper option over the whole of the next five years, that doesn’t mean there won’t be a few conviction tests along the way. The Bottom Line: The five-year GoC bond yield spiked last week in response to the Fed’s taper talk, and if it rises much more, our five-year fixed rates will start to increase.

The Bottom Line: The five-year GoC bond yield spiked last week in response to the Fed’s taper talk, and if it rises much more, our five-year fixed rates will start to increase.

Variable mortgage rates held steady last week, and that still isn’t expected to change for at least another year or so.

When the Fed follows through with its tapering plans, GoC bond yields and our fixed mortgage rates may rise for a time, but I think there is also a good chance that they will settle back down as inflationary pressures ease, and as economic data on both sides of the 49th parallel come in lower than our central bankers are currently projecting.