Why Our Record Employment Gains Aren’t Impacting Mortgage Rates

July 13, 2020Dave Is Currently Dockside

July 27, 2020COVID-19 is redefining the world as we know it.

Jobs. Trade. Rules for basic human interaction. They are all now in flux.

The Bank of Canada’s (BoC) unorthodox announcement last week was the latest proof.

Once again it kept its policy rate nailed to its 0.25% floor, as expected, and that left variable mortgage rates unchanged. But the Bank also made clear for the first time that borrowers could count on rates staying low for years to come.

The BoC has a well-earned reputation as a conservative central bank. It didn’t engage in any quantitative easing (QE) during the 2008 financial crisis, unlike so many of its counterparts, and since then it has been slower to cut rates and quicker to raise them. That’s what made last week’s Monetary Policy Report (MPR) and accompanying press conference commentary so surreal.

In short order the Bank has now slashed its policy rate to the floor and started QE at a dramatic rate. Last week, BoC Governor Tiff Macklem reiterated its commitment to buying at least $5 billion/week in government and corporate debt for an extended period. The BoC may have been slow to take up QE, but it is now pumping it out at a rate that would make any profligate central banker blush.

The Bank’s latest MPR was also unprecedented. Instead of including its usual economic forecasts, it offered only a “central scenario”, which was positioned as the Bank’s best guess of how the pandemic may impact our economy in the years ahead.

Strange times indeed.

Here are my five takeaways from the Bank’s latest meeting that will be of note to anyone keeping an eye on mortgage rates, followed with my two cents on the slam-dunk mortgage option for most borrowers today.

- Forget recession. We may be at the start of a depression.

The BoC didn’t use the word depression, but our current economic conditions could take us there.

Investopedia.com defines a depression as “a slowdown that lasts at least three or more years and leads to a drop in GDP of at least 10%.”

Three-year time frame?

The BoC wants to see evidence of a full recovery before raising rates. That could easily take until late 2022/early 2023, which would put us about three years from the start of the crisis.

A 10% drop in GDP?

In its latest MPR, the BoC predicted that “it will take a long time for economic activity to get back even to the level where it was at the end of 2019, before the pandemic struck.”

The negative economic shock created by COVID impacted existing businesses quickly, and it will take time for new businesses to take root and grow to replace that lost economic output.

Economic forecasts seem like a waste of time at the moment, but a 10% drop in GDP certainly seems within the realm of possibility.

If you think the term depression sounds dramatic, consider that the BoC has called the current crisis “the steepest and deepest economic decline since the Great Depression” and has called it a “historic shock … [that] has demanded a historic policy response.”

Economist David Rosenberg recently explained that depressions are different from recessions because they cause “a secular shift in attitudes in terms of how we live, how we work and how we travel, and our approach toward debt and spending.”

The BoC’s latest MPR notes “significant changes in behaviour” and predicts lasting changes in employment, saving rates, immigration, travel, and basic consumption. So much so that Statistics Canada just devised a new inflation measure called its “Analytic Pricing Index”, which adjusts for COVID-related changes in spending (like more groceries and less travel).

- The BoC’s central scenario sounds optimistic.

The BoC acknowledged “fundamental uncertainty about the course of the virus” and “considerable uncertainty about its impacts.” Its central scenario assumes the following:

- No broad-based second wave

- A gradual lifting of most large-scale containment measures

- A widely available vaccine or widespread access to effective treatment by mid-2022

It never hurts to hope, but apparently every other pandemic in history has had a second wave, and thus far, the countries that have reopened most aggressively have experienced the biggest resurgences. We can manage the pandemic either quickly or correctly, but probably not both.

The Bank’s central scenario depends on a vaccine by mid-2022. Again, let’s all hope for that.

In its worst-case scenarios, the BoC sees the potential for “increasingly dire” outcomes, ranging from a second wave to widespread defaults (that include sovereign debt) to an escalation in trade tensions. Its more optimistic scenarios centre on the timing of when a vaccine or effective treatment for the virus will be widely available.

I can imagine the former much more easily than the latter. Apparently so can Governor Macklem because he made it clear that the Bank sees the risks during this “unprecedented fall in economic activity” tilting to the downside.

- We’re looking at a two-phase recovery.

The BoC predicts that our recovery will be broken into two phases: a “re-opening phase” of “exceptionally strong near-term growth” followed by “a slower and bumpier recuperation phase.”

Put simply, once mandated shutdowns are lifted, some businesses that only closed because they were required to will come quickly back online. After that, the recovery will enter a long, slow, protracted and uneven stage as other businesses fail or recalibrate. The Bank believes that many workers and businesses will face “an extended period of uncertainty” as the crisis exerts “long-lasting adverse effects on the productive capacity of the economy.”

That’s on the supply side. The Bank expects that demand will take even longer to recover, especially as changes in consumer behaviour become more entrenched. To quote Governor Macklem: “It’s going to be a long climb.”

- The U.S. dollar isn’t responding as expected.

This hasn’t been talked about much, but the BoC noted that the U.S. dollar isn’t behaving like it normally would during a crisis.

The Greenback is the world’s reserve currency, and as the ultimate safe-haven asset, it should be in high demand (and price) at a time like this.

The BoC observed that the “US dollar has depreciated somewhat against major currencies since April, including the Canadian dollar. Safe-haven flows into assets denominated in U.S. dollars declined, and some flows reverted to assets denominated in other currencies.”

Could COVID spur the end of the Greenback’s run as the world’s undisputed reserve currency? Several factors have pushed global trade in that direction: trade wars, rising U.S. debt levels and the lessening international demand for U.S. debt, U.S. mismanagement of the COVID crisis, and the growing importance of China.

The Greenback’s world reserve currency status affords the U.S. many economic benefits, and losing them would create a lasting economic headwind for America that would blow north to Canada as well.

- Mortgage rates aren’t going anywhere (except maybe down).

BoC Governor Macklem left no doubt about where rates are headed when he said: “We are being unusually clear that interest rates are going to be low for a long time.”

It is unusual for a central bank with a conservative reputation to be so clear.

For a Bank that has eschewed offering forward guidance, that blunt admission reveals much about the severity of the current crisis as well as the BoC’s willingness to do whatever it can to counteract its “strongly disinflationary” impacts.

On a related note, in case you were wondering, the BoC is still concerned about our household debt levels. It is just willing to accept that particular risk ahead of other risks that it fears more at the moment. (That too should tell us something about the BoC’s view of what may be ahead.)

What should you do if you need a mortgage in the current environment?

I continue to believe that a five-year variable-rate mortgage is the slam dunk option today for borrowers who are prepared to live with the remote risk that rates will rise sooner than is now almost universally expected (because that risk will never completely go away).

In this recent post I made the case for variable rates in detail. Here is a summary of my conclusions:

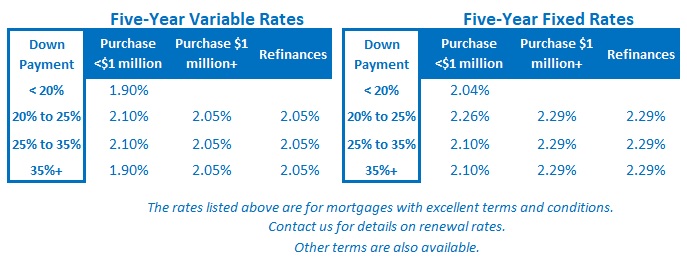

- Today’s variable rates are lower than their fixed-rate equivalents and don’t appear likely to rise any time soon.

- Variable rates come with a free option to convert to a fixed rate at any time. If fixed rates continue to fall as expected, you may be able to convert down to a lower fixed rate later.

- The penalty to break most variable rate mortgages is only three months’ interest (whereas fixed-rate penalties are calculated using the greater of three months’ interest or the potentially expensive interest-rate differential penalty).

Now that the BoC has made guessing a respectable enterprise, here’s mine: I think today’s rates will seem high in a year’s time. I won’t be happy if I’m right. In fact, I’ll even hope that I’m wrong if it means we’ll be free of this pandemic sooner than expected.

The Bottom Line: Fixed and variable rates held steady last week.

The Bottom Line: Fixed and variable rates held steady last week.

The BoC is determined to keep rates from rising until our economic recovery is well underway, and that portends mortgage rates that are the same as or lower than today for years to come. Against that backdrop, the low cost and more flexible variable-rate options are compelling.