Canadian Mortgage and Real-Estate Predictions for 2024

January 8, 2024When Will the Bank of Canada Start to Cut?

January 22, 2024 Almost everyone’s 2024 mortgage-rate forecast assumes the Bank of Canada (BoC) will cut its policy rate at some point this year, with opinions differing only on the number and timing of the cuts.

Almost everyone’s 2024 mortgage-rate forecast assumes the Bank of Canada (BoC) will cut its policy rate at some point this year, with opinions differing only on the number and timing of the cuts.

BoC Governor Macklem has said that the Bank will start to cut when it is satisfied that inflation is “on a clear path” back to 2%. That criterion prompts an important follow-up question: Which measure of inflation will it focus on?

Our overall Consumer Price Index (CPI) came in at 3.1% (annualized) in November, and our core CPI, which strips out volatile food and energy costs, was 2.8% (annualized) over the same period. The BoC also closely watches two sub-measures of core inflation. CPI-trim stood at 3.5% (annualized) in November, and CPI-median came in at 3.4% (annualized).

None of those data points are close to the BoC’s 2% inflation target. If the Bank is going to focus on those gauges, its first rate cut will likely take longer to materialize than the current consensus forecast of sometime in Q2.

But a different iteration of our current inflation data, which several economists are now focusing on, supports the view that inflation has already cooled sufficiently.

Shelter costs, which make up the largest single component of our CPI (28% of the total) are the main drivers of our current inflation pressure. If we exclude that component from our CPI, we get an inflation rate of 2.1% (annualized) in November. By that measure, we’re not “on a clear path” back to 2%, we’re pretty much there already.

I grant that it’s easy to cherry pick data to produce a desired outcome, but there is a reasonable argument to be made for looking past the inflation pressure coming from our shelter-cost component.

For starters, one of the causes of the current price pressure on shelter costs is higher mortgage rates, which is inflation of the BoC’s own making (and which will be mitigated once it starts cutting rates).

But shelter costs are also being driven higher by rising rents, which are tied to housing shortages brought on by record levels of immigration. Our federal government’s failure to align its housing policy with its immigration policy is a structural problem that higher policy rates can never solve.

This wouldn’t be the first time the BoC has looked past price rises that it can’t control. For example, when inflation began to spike during the pandemic, the Bank attributed most of the rise to global supply shortages and other lockdown disruptions that were beyond its influence, and it initially held its policy rate steady in response. On the other hand, if the Bank doesn’t remove the shelter component of our CPI from its calculations, the resulting overtightening will produce a harder economic landing than should otherwise be necessary.

Last week during her talk at the Economic Club of Canada (thanks to First National for the invite), TD’s Chief Economist Beata Caranci noted that if our CPI shelter costs remain at their current levels (6%+ year-over-year), all of the other prices that comprise our CPI will have to stop increasing altogether in order for our overall CPI to return to the Bank’s 2% target level.

In other words, if the BoC isn’t willing to look past the current price pressure on shelter costs, it will need to eliminate all other inflation.

Now let’s tie this back to where Canadian mortgage rates may be headed.

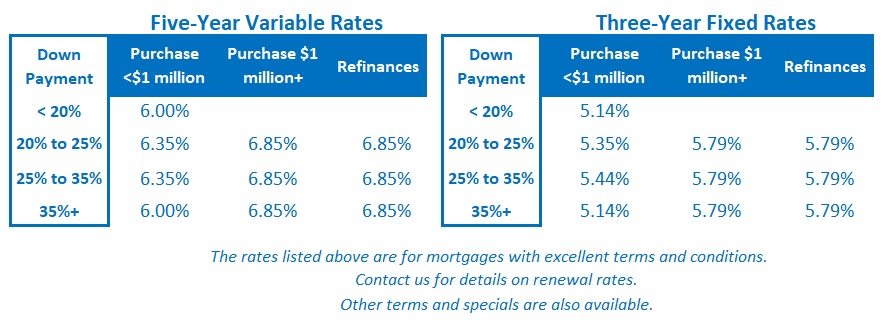

The bond market is pricing in the first BoC rate cut in Q2, and the consensus believes that we’ll see total rate cuts of between 1% to 1.5% this year. Current Government of Canada (GoC) bond yields and our fixed mortgage rates reflect those expectations.

If the BoC makes it clear that it won’t discount today’s elevated shelter costs when assessing our current inflation conditions, it is more likely that rate cuts will take longer to materialize. Variable-rate borrowers would therefore have to wait longer for rate relief. GoC bond yields, and the fixed mortgage rates that are priced on them, would also likely move higher in response.

Conversely, if the BoC acknowledges the narrow profile of our current inflation pressure and the fact that lower rates will help reduce shelter costs, that would support the consensus rate view that is currently priced in.

The BoC’s next policy rate decision will be issued on January 24, so we won’t have to wait long for its next inflation assessment (and its next Monetary Policy Report, for Q1).

It’s not obvious to me how the BoC will thread this needle.

On one hand, removing the CPI shelter data and cutting rates before inflation is on a clear path to 2% could cause inflation expectations to move higher and undermine the BoC’s efforts. But ignoring the fact that shelter-price pressures are being caused by structural factors like immigration and the BoC’s own relatively high policy rate may well lead to over-tightening and cause unnecessary economic pain.

The BoC is in a dilly of an inflation pickle. The Bottom Line: GoC bond yields fell a little last week, and lenders sharpened their pencils with another round of cuts to their fixed mortgage rates. Gross lending spreads are now back within their long-term ranges. That should cause them to hold steady until a new catalyst emerges.

The Bottom Line: GoC bond yields fell a little last week, and lenders sharpened their pencils with another round of cuts to their fixed mortgage rates. Gross lending spreads are now back within their long-term ranges. That should cause them to hold steady until a new catalyst emerges.

Five-year variable rate discounts were unchanged last week. Variable-rate borrowers should get a better sense of when their first rate cut is likely to materialize if/as the BoC offers insight into how it will weigh hot shelter prices against much cooler price momentum almost everywhere else.