New Mortgage-Rule Changes: HELOCs & Reverse Mortgages

July 4, 2022Five Thoughts on the Bank of Canada’s Jumbo Rate Hike

July 18, 2022 The Bank of Canada (BoC) is expected to increase its policy rate by 0.75% when it meets this Wednesday, and if that happens, our variable mortgage rates will rise by the same amount in short order.

The Bank of Canada (BoC) is expected to increase its policy rate by 0.75% when it meets this Wednesday, and if that happens, our variable mortgage rates will rise by the same amount in short order.

Right now, the BoC’s policy rate stands at 1.50%, which is below its estimated neutral-rate range of 2.25% to 3.25%.

(The neutral-rate range is the rate level that neither stimulates nor reduces target inflation when the economy is operating at full capacity.)

The BoC is in a hurry to raise rates and course correct.

Prices have surged higher, albeit in large part due to factors that are beyond the Bank’s control. But also, in retrospect, it left its policy rate too low for too long.

Canadian consumers and businesses now expect inflation to remain elevated for an extended period. Those expectations are feeding into buying decisions and are compelling a growing number of workers to demand increased compensation to regain their lost purchasing power.

We’re now at an interesting point for wages.

The argument that we’re not headed for the soaring inflation of the 1970s has always depended on our labour market’s current lack of large collective bargaining units. Back then, workers were able to negotiate inflation-protected compensation that led to a self-reinforcing wage-price spiral.

That history is unlikely to repeat, because we don’t have as many of those powerful bargaining groups around these days, but individual workers have increased bargaining power right now, so it could certainly rhyme if labour is scarce and inflation remains elevated.

On that note, average year-over-year wage growth surged higher from +3.9% in May to +5.2% in June. Labour is the largest single cost for most businesses, so rising labour costs will cause prices to rise and add momentum to broader inflation.

Persistently rising inflation has narrowed the BoC’s window for keeping labour costs contained.

The consensus now expects the Bank to keep raising its policy rate from its current 1.50% level until it reaches the upper end of its neutral-rate range, or to about 3%, before pausing to assess the impacts from its series of sharp increases, which can take up to two years to fully materialize.

If that is their plan, many informed observers think the Bank might as well get up to that level as quickly as possible. But there are also some points to be made in favour of moving less dramatically.

For starters, the neutral-rate range that everyone is consistently quoting is a theoretical construct that is hard to calculate and is as much art as science. It is also a moving target.

More importantly, our economy now contains record levels of debt that are magnifying the impact of each rate hike to an extent that is hard to measure.

We are already seeing signs of a slowdown in our economy, perhaps more quickly than would typically be expected. Our GDP contracted by 0.2% in May on a month-over-month basis and shed an estimated 43,000 jobs in June, and activity in our important real-estate sector has already slowed sharply.

Normally, the BoC hikes rates when our economy is over-heating to curb excess demand. But this time, it is tightening into slowing momentum, trying to reduce demand to meet supply at its currently impaired levels.

While it is true that fear of inflation can become a self-fulfilling prophecy, so too can fear of recession. Business and consumer confidence surveys have nose-dived of late as an increasing number of Canadians subscribe to the view that the BoC’s rate increases will cause our economy to slump.

Policy-rate hikes aren’t the only form of monetary-policy tightening taking place these days either. Both the BoC and the Fed used extensive quantitative easing (QE) to drive down bond yields, and the fixed rates that are priced on them, during the pandemic. Both have also now reversed to quantitative tightening (QT) instead, and that is producing the opposite effect on yields.

It’s no accident that the shift to QT has occurred alongside the sharpest rise in bond yields (and the fixed mortgage rates that are priced on them) that we have seen in almost forty years.

Rate hikes, QT, and slowing momentum. Our policy makers would be wise to err on the side of caution as they venture into these choppy waters.

Some market watchers believe that the US Federal Reserve created cover for the BoC when it enacted a 0.75% rate hike at its last meeting – but it should be noted that the Fed funds rate had lagged the BoC’s policy rate up until then, and US inflation (8.6%) remains higher than ours (7.7%).

A less dramatic hike would also allow the BoC a little more time to grasp what happens to inflation over the short term, and there are already signs of easing pressures. The prices for oil and other commodities have fallen significantly of late, shipping costs are starting to normalize, and concerns about the health of our economy may now keep more people up at night than worries about inflation.

The BoC’s immediate priority is to wrest back control over the inflation narrative, and I expect its next rate hike, policy statement, and accompanying Monetary Policy Report to all work toward that end. But I also believe that objective can be achieved with a policy-rate rise of just 0.50% this Wednesday, instead of the 0.75% hike that is being so widely predicted. The Bottom Line: The five-year GoC bond yield rose by about 0.20% last week, but the 0.50% drop the week prior still leaves a little room for mortgage lenders to cut their fixed rates from their current levels.

The Bottom Line: The five-year GoC bond yield rose by about 0.20% last week, but the 0.50% drop the week prior still leaves a little room for mortgage lenders to cut their fixed rates from their current levels.

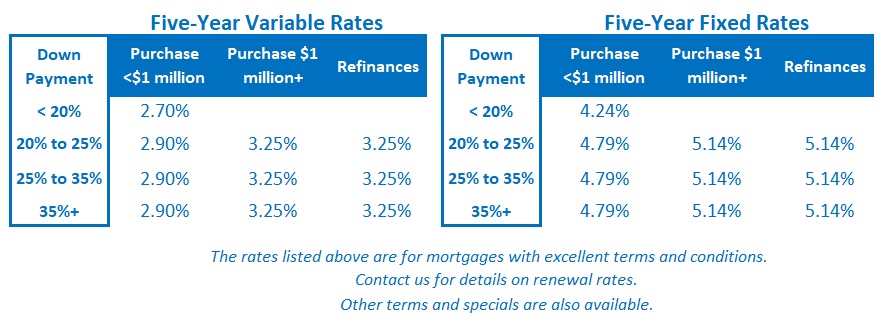

Variable rates will increase this week, by either 0.50% or 0.75%. We’ll get the answer on Wednesday, and I’ll report back next Monday.

I continue to believe that five-year variable rates will prove cheaper than their fixed-rate equivalents over their full terms. That belief is underpinned by two assumptions:

- It is unlikely that the current gap of about 2% between variable and fixed rates will close entirely, and if I’m right, that will leave at least some saving for variable-rate borrowers.

- If I’m wrong and the BoC increases by more than expected, I think that will greatly increase the odds that a sharp economic slowdown, and rate cuts, would then follow.

4 Comments

Hi David, great insights as usual. I read somewhere that the US manipulates its consumer price index to keep it low. for example replacing a steak with ground beef and claiming it is the same. while this is technically still beef it is not the same. Do you know if the same is done in Canada and if so what our real CPI is?

Hi Nalaka,

The CPI is regularly adjusted in both the US and Canada.

Some items are removed/added to the index, or reweighted as consumer spending habits change. These are referred to as hedonic adjustments, and they are often debated (and criticized).

In answer to your question, since CPI is always changing there is no “real CPI” that everyone will agree on, beyond the officially reported statistic.

Best,

Dave

As always, great explanation and perspective! Currently regretting not going fixed rate a year ago. That ship has sailed though and I’ll ride this rollercoaster out. I feel that the BoC is over estimating, I think we are much closer to a recession than they realize and I am anticipating a rate correction by this time next year. Time will tell

Thanks Mitch. We’ll see what happens, but I agree with your general view.

Best,

Dave