Why the Bank of Canada Is About to Hike by Another 0.75%

October 24, 2022The Fed Hiked and Financial Markets Shuddered

November 7, 2022The Bank of Canada (BoC) raised its policy rate by 0.50% last week. This was the Bank’s sixth hike thus far in 2022, and its policy rate has now increased from 0.25% to 3.75% over that span.

The move surprised financial markets, which had priced in a 0.75% hike, and Government of Canada (GoC) bond yields plunged in the immediate aftermath as investors recalibrated their assumptions of when the BoC will pause and where rates will peak.

In today’s post, I will offer my key takeaways from the Bank’s latest policy statement, press conference, and accompanying Monetary Policy Report (MPR).

The BoC Didn’t Pivot

The most popular hot take in response to the BoC’s smaller than expected hike was that it had just pivoted from a hawkish monetary-policy stance to a more dovish one in response to concerns about our slowing economic momentum.

I think that is a misread.

The Bank warned that “the policy rate will need to rise further”. It observed that inflationary pressures both at home and abroad “remain high and broadly based” and noted that “near-term inflation expectations remain high, increasing the risk that elevated inflation becomes entrenched”.

That said, while the Bank did not pivot, its carefully chosen wording may indicate that we could see a near-term pause in rate hikes (which seems appropriate after the rapid series of hikes we have just experienced). By its own estimate, the Bank assumes that it will take up to two years for its rate increases to exert their full bite on our economy, and our record-high household and government debt levels will increase the magnitude of those impacts this time around.

A near-term pause may be in the cards after at least one more hike at the next meeting, but a pause is not a pivot, and if inflationary pressures do not abate, the Bank will have no choice but to do what it must to bring them to heel.

On that note, the Bank reiterated its intentions at the end of its MPR when it warned that while it viewed the risks to its inflation outlook as “roughly balanced, the upside risk is of greater concern because inflation is persistently high.”

Inflation Has Probably Peaked, But Only Just Barely

Much has been made of the fact that our overall Consumer Price Index (CPI) has fallen from 8.1% to 6.9%, but the BoC attributed that drop to a cooling in previously red-hot gasoline and agriculture prices and not to a broad easing of price pressures (which would be a much more encouraging sign).

Instead of focusing on our overall CPI, the Bank reiterated its concern that “price pressures remain broadly based”, and it observed that two-thirds of the CPI components have increased by more than 5% over the past year.

The Bank also reminded us that it will rely most heavily on its core inflation measures “CPI-trim” and “CPI-median” when assessing our current inflationary pressures, and it noted that these measures are “not yet showing meaningful evidence that underlying price pressures are easing”. (For clarification, CPI-trim and CPI-median have only fallen by 0.3% and 0.2% respectively from their recent peaks.)

Simply put, anyone who is focusing primarily on our overall CPI is over-estimating the extent to which inflation has declined from its peak thus far.

It Is Still Hard to Tell Where Rates Will Top Out

After living through eight months of rates ratcheting sharply higher, we are all understandably keen to see any signs of relief on the horizon. Governor Macklem offered some solace when he said, “This tightening phase will draw to a close. We are getting closer”, although he immediately added “we are not there yet.”

Here are some thoughts on how much higher the BoC may go.

The market thinks the Bank will hike by another 0.25% to 0.50% at its next meeting or two and then stop. When we get to that point, many market watchers will conclude that the peak for rates is in. But not necessarily, because again, a pause doesn’t mean a pivot.

The belief that we will see rates hold at those levels is tied to the assumption that inflation will fall back to more normal levels in the next year or two. But, so far, inflation hasn’t done what many of us thought it would, and the assumption that it will soon moderate is increasingly challenged by ongoing developments.

Supply chains are evolving to become more reliable, but that often makes them more expensive. Wages, which are just about the stickiest cost, are still rising at 5%+ for both structural and pandemic-related reasons. A subset of Canadian consumers still has excess savings to draw on, and that could make demand more resistant to higher interest rates.

While it is reasonable to expect rates to stop rising after one more increase by the BoC at its next meeting, anyone who then conflates that pause with a pivot by the BoC hasn’t been listening carefully to what the Bank has been saying.

Rates are going to keep rising until both inflation and inflation expectations fall materially. Full stop.

The BoC Came Pretty Close to Forecasting a Recession

Eleven out of our past fourteen Fed rate-hike cycles have led to US recessions, and while Canadian data are harder to come by, our results would almost certainly mirror those seen in the US.

Central bankers are beholden to inflation data, which are lagging indicators, when determining how to adjust policy rates that will impact their economies about two years down the road. Is it any wonder that delayed responses often lead them to overtighten?

The BoC has finally cast aside its soft-landing forecast and now projects slower GDP growth over the next three years. Notably, it now projects GDP growth of only 1% in 2023.

At his press conference, Governor Macklem said, “we expect growth will stall in the next few quarters – in other words, growth will be close to zero”. Then he hedged a little further by adding, “this suggests that a couple of quarters with growth slightly below zero is just as likely as a couple of quarters with small positive growth.”

This is probably about as close as the Bank will get to forecasting an outright recession.

The Gap Between Canadian and US Policy Rates is About to Widen

For myriad reasons, the US Federal Reserve will likely need to raise its policy rate by more than the BoC to cool US inflation. For example, US inflation is higher, US household debt levels are lower, and the US economy is much less reliant on interest-rate sensitive sectors like residential real-estate for its economic growth.

Up until now, the Fed and BoC policy rates have closely mirrored each other. That has helped the Loonie hold up against the Greenback and has helped to reduce the amount of inflation that we import from the US. But that is about to change.

The Fed is expected to raise its policy rate by 0.75% when it meets this week, and that will push it 0.25% above the BoC’s policy rate. The futures market is also forecasting more aggressive hiking by the Fed at its next several meetings, and at least for now, it has the Fed funds rate peaking at 5.25% and the BoC’s policy rate peaking at about 4.25%.

As the gap between US and Canadian policy rates widens, the Loonie will weaken, and that could conceivably stoke (imported) inflationary pressures to an extent that might compel the BoC to keep hiking past the point that it would otherwise choose. If that comes to pass, it will add another economic headwind to the mix.

Thoughts for Mortgage Borrowers

I need to start by acknowledging the risk that today’s inflationary pressures will take longer to abate than previously expected and that the BoC may therefore be compelled to raise its policy rate higher than both the Bank and the market currently expect.

If that happens, and, to be clear, I hope it doesn’t, variable mortgage rates could increase by more than the 0.50% or so that is currently anticipated.

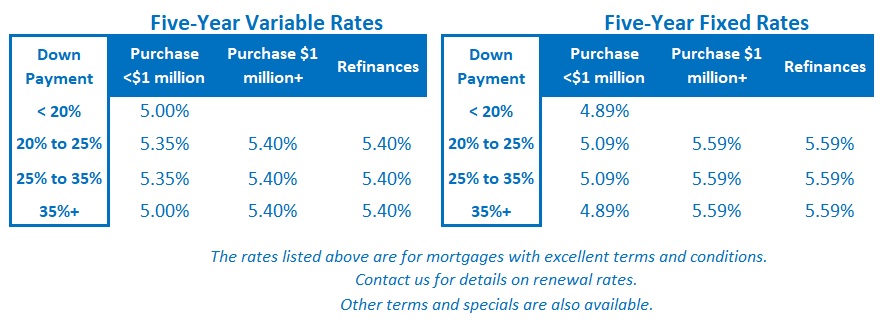

With that in mind, I would recommend a variable rate only to borrowers who can handle an increase above 0.50%, and regardless of whether they select an adjustable-payment variable (where payments fluctuate in response to rate changes) or a fixed-payment variable (where payments stay the same and the time required to fully amortize the mortgage adjusts instead).

I believe that the BoC and the Fed will eventually reduce inflation to a point where their policy can drop from their current levels, and at that point lower variable rates will follow. The challenge is not so much figuring out the shape of the curve, but rather its timing.

If you’re starting a five-year variable-rate term today, I think there should be enough time after inflation has begun its decline for you to achieve an overall saving versus today’s fixed-rate options. That said, if you currently have a variable-rate mortgage with less than half of your term remaining and have been itching to lock in, last week’s plunge in GoC bond yields may soon present the opportunity to convert at lower rates (before they resume their upward march – which I expect they will in short order).

If you prefer the stability of a fixed rate, I think shorter-term fixed rates are worth a look, even though they are more expensive now. Today’s fixed rates have just undergone their sharpest increases in forty years and they will drop back down when inflation eventually moderates. The sooner you can be free to reset your rate after that, the better.

With all of that said, my rate predictions are anywhere and always the best guesses of an informed but imperfect observer, and if you prefer the stability of a five-year fixed rate, which gives you maximum predictability at a time of heightened uncertainty, do yourself a big favour by ensuring that your mortgage contract doesn’t come with a prohibitive penalty if rates fall materially and you want to renegotiate before the end of your term.

Forewarned is forearmed. The Bottom Line: GoC bond yields plunged last Wednesday in response to the BoC’s decision to raise its policy rate by less than the market (and this mortgage blogger) expected.

The Bottom Line: GoC bond yields plunged last Wednesday in response to the BoC’s decision to raise its policy rate by less than the market (and this mortgage blogger) expected.

If those bond yields stay at current levels, some cuts to fixed mortgage rates should be imminent (but it is worth remembering that lenders take the elevator when they raise rates and the stairs when they lower them).

Variable-rate borrowers will see their rates rise by another 0.50% in response to the BoC’s hike last week, and the market is pricing in another 0.50% increase before the Bank pauses.

What happens after that will depend on what happens with inflation. If it proves more stubborn than expected, peak variable rates may be higher than the consensus currently expects (although I still believe that the BoC’s aggressive series of rate-hikes will cause a recession and that rate cuts will follow thereafter).