Mortgage Strategies for the Coronavirus Crisis

March 23, 2020The Slam Dunk Mortgage Option Right Now (and a Warning about HELOCs)

April 6, 2020 Last week our economy slowed to nearly a halt as self-quarantined Canadians hunkered down to wait out the COVID-19 threat.

Last week our economy slowed to nearly a halt as self-quarantined Canadians hunkered down to wait out the COVID-19 threat.

Our policy makers have taken unprecedented steps to try to slow our infection rate to a level that our health-care system can cope with, a concept now commonly referred to as flattening the curve. At the same time, they are trying to minimize the economic trauma inflicted by the virus by introducing a broad range of fiscal and monetary policy actions on an unprecedented scale.

As extraordinary as these measures are, they seem entirely appropriate for an economy coping with both COVID-19 and a barrel of Western Canadian Select oil priced at $6.10 (when I last checked).

In today’s post I’ll detail how Canadian monetary policy entered a new phase last week and offer my take on the implications for our fixed and variable mortgage rates going forward.

Let’s start with a recap of what was a remarkable week for mortgage-related announcements. Some of this gets a bit technical, but you can’t fully appreciate the scope and scale without diving into the detail.

On March 16 the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) announced that it would purchase $50 billion worth of insured mortgages from lenders in order to free up their balance sheets for additional lending. On March 20 it announced that previously uninsured mortgages would also be eligible, and then last Thursday, on March 26, CMHC increased its planned budget to $150 billion. (To put that in perspective, $150 billion works out to about 80% of all of the insured mortgages currently sitting on our lender’s balance sheets.)

Last Thursday CMHC also announced that the Canada Mortgage Bond (CMB) program’s current limit of $186 billion will be increased by up to $60 billion. Our lenders love the CMB program because it allows them to borrow at virtually the same rates that our federal government pays on its Government of Canada (GoC) bonds. It only goes so far though. Lenders have caps on how much they can sell into the CMB program. When they hit their limit, they have to use other, more expensive funding sources. This announcement gives lenders expanded access to their cheapest funding source.

Last Friday the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI), our banking regulator, announced that it will allow our largest banks to reduce their capital buffers from 2.25% to 1.00%. It estimates this move will increase overall lending capacity by $300 billion. OSFI also confirmed that loans with payments being deferred as a result of COVID-19 will not be counted as non-performing.

Also on Friday, the Bank of Canada (BoC) announced that it would purchase $5 billion worth of federal and provincial  government debt per week and will continue to do so “until such time as the recovery is well underway.” The Bank’s primary objective is to ensure that there will always be a liquid market for our government debt, meaning that it can be bought and sold quickly and in large amounts. The BoC’s ongoing interventions will put downward pressure on GoC bond yields (which our fixed mortgage rates are priced on).

government debt per week and will continue to do so “until such time as the recovery is well underway.” The Bank’s primary objective is to ensure that there will always be a liquid market for our government debt, meaning that it can be bought and sold quickly and in large amounts. The BoC’s ongoing interventions will put downward pressure on GoC bond yields (which our fixed mortgage rates are priced on).

In addition, the BoC committed $24 billion to our short-term commercial paper market for the same reason – to give buyers and sellers confidence that there will always be a liquid market. This is learned wisdom. Our commercial paper market seized up during the 2008 financial crisis. It had a devastating impact on our economy and took years to clean up.

As you may also have heard, the BoC cut its policy rate by another 0.50% last Friday, bringing it down to 0.25%. That’s a level we’ve reached only once before, during the Great Recession in 2009. The speed of the Bank’s cuts is the part I find most surprising. After nearly five years with no decreases, the BoC’s policy rate has dropped all the way from 1.75% to 0.25% in March.

BoC Governor Poloz made it clear that the Bank has an “unlimited” range of other monetary-policy options available if needed, but he emphasized that it will play a “complementary role” to our federal government’s fiscal policy actions over the short term. The BoC’s hope is that last week’s initiatives will “lay the foundation for the economy’s return to normalcy” after the immediate crisis has passed.

Now on to the key question for readers of this blog: What will all of this mean for Canadian mortgage rates?

Let’s start with the good news.

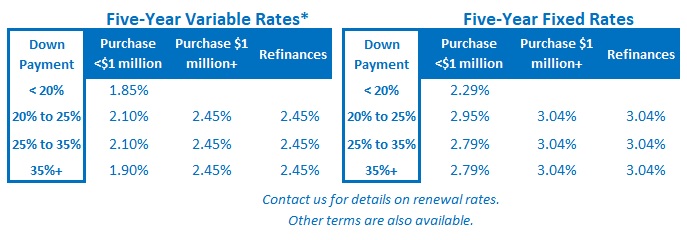

With lender prime rates now down to 2.45%, anyone with an existing variable-rate mortgage is probably paying a rate that is either at or a little below 1.85%. That saving will surely come in handy during the months ahead.

Existing fixed-rate borrowers who were hoping to refinance down to lower rates aren’t as lucky.

The five-year GoC bond yield, which our five-year fixed mortgage rates are priced on, now hovers at about 0.75%. Lenders typically set their rates at about 1.25% to 1.50% over that level, which would translate to five-year fixed rates in the 2.00% to 2.25% range. But today’s five-year fixed rates are offered at closer to 3%, and the rates offered on other fixed-rate terms are typically higher.

New borrowers who are considering a variable rate will encounter a similar reality. Lender prime rates have fallen through the floor, but the usual discounts off prime have essentially vanished. (There is one lender still offering variable rates in the prime minus .50% range, but they sent out a note last week estimating their current turnaround time at “more than 20 days”).

To be clear, a five-year variable rate of 2.45% is still a decent option today. It offers many existing fixed-rate borrowers who have mortgage contracts with fair prepayment penalties a net saving if they refinance, and it starts new borrowers with a rate that is among the lowest ever offered.

Variable rates also come with a free option to convert to fixed at any time and a penalty of only three months’ interest if more competitive rates can be found elsewhere. That said, the BoC has made it clear that its policy rate is now at the bottom of its range, and as the current crisis goes, so too go the rates that were lowered in response to that crisis. Caveat emptor.

I am fielding a lot of calls from borrowers who are wondering why mortgage rates aren’t lower given that lenders have benefitted from these changes in just about every way possible:

- Lowest borrowing rates in history

- Cash rich balances sheets

- Reduced capital buffers

- Expanded access to their cheapest funding source

- Reduced risk premiums thanks to BoC guaranteed market liquidity

- No pressure from OSFI on deferred mortgage payments

My response is simple.

Nearly one million Canadians have applied for unemployment benefits over the past two weeks (and that doesn’t include many other working Canadians, whose incomes have been severely impacted by COVID-19 but who aren’t eligible). Not surprisingly, our lenders’ customer service departments are now overwhelmed with calls from existing borrowers asking about Deferred Mortgage Payment programs.

Is it any wonder they are increasing their spreads against that backdrop? The Bottom Line: Last week our policy makers enacted a historic series of fiscal and monetary-policy measures designed to bolster our economy while we self-isolate in an attempt to flatten the COVID-19 curve.

The Bottom Line: Last week our policy makers enacted a historic series of fiscal and monetary-policy measures designed to bolster our economy while we self-isolate in an attempt to flatten the COVID-19 curve.

Among those initiatives, the BoC dropped its policy rate to 0.25%, and lenders responded by promptly lowering their prime rates to 2.45%. The Bank also made it clear that its policy rate is now at the bottom of its range, so variable-rate borrowers shouldn’t expect any further cuts going forward.

Last week’s actions are also likely to flatten another curve: the GoC bond-yield curve, which our fixed mortgage rates are priced on – although lenders have understandably added significant spreads to their offered rates for the time being.

3 Comments

Great Read!

Kindly correct me if I am wrong, how come the risk of mortgage deferment or default of many borrowers justify the lenders’s rate increase, when the CMHC is taking this risk by purchasing 80% of insured mortgages? Shouldn’t this mean that the lenders are guaranteed their capital and profits with no risk? Also, I read but can’t remember exactly that some entity whether CMHC or BoC or Gov will be extending the purchases to cover the uninsured mortgages as well.

So how come the lenders are hedging for any risk! Is it the remaining 20% + the uninsured mortgages justify the rate increase???

Would NOT these actions by the lenders antagonize the relief efforts made by the Gov and BoC, and stop these measures from trickling down to the average person and consequently slowing the economy even more??

Hi Mourad,

CMHC is purchasing the insured and uninsured mortgages that are already on the lender’s books, not new ones through the door (that said, it’s still a bailout in my book).

Defaulted loans are still very bad for lenders even if they are insured and/or off balance sheet. (For a host of reasons that require a longer explanation than I have time for here.) Bottom line, lenders aren’t going to compete for new business when 1 million Canadians have filed for EI with more people lining up behind them each day.

Our regulators are trying to facilitate ultra loose credit conditions for lenders in the hopes that they will keep lending because they know how scared lenders are at the moment. That said, they can’t force them to lend (and if you and I were in their shoes we would be pulling back as well).

Best,

Dave