Why Slowing Consumer Spending Will Put a Lid on Canadian Mortgage Rates

October 16, 2017The Bank of Canada Holds Rates Steady and Dampens Rate-Hike Expectations

October 30, 2017 Last week the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) announced three changes to its B-20 guidelines, which are otherwise known as the mortgage rules that must be used by all federally regulated lenders.

Last week the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) announced three changes to its B-20 guidelines, which are otherwise known as the mortgage rules that must be used by all federally regulated lenders.

This sixth round of B-20 changes since the financial crisis in 2008 will take effect on January 1, 2018. If past is prologue, the changes will apply to new applications submitted on or after that date (and pre-approvals that are converted beyond January 1 will be subject to the new rules as well).

In today’s post I outline the latest changes and offer my take.

Change #1: “OSFI is placing restrictions on certain lending arrangements that are designed or appear designed to circumvent LTV (loan-to-value) ratio limits.”

(Reminder: LTV ratios measure the value of the mortgage as a percentage of the value of the property. For example, a borrower with a mortgage of $500,000 on a property worth $1,000,000 has an LTV ratio of 50%.)

As the mortgage rule changes have piled up, some banks have come up with creative ways to circumvent them. For example, if a borrower needed a 20% down payment to qualify but didn’t have that amount, some banks began providing supplemental, unsecured credit to fill the gap.

OSFI, perhaps remembering former TD bank chairman Ed Clark’s cry to “save us from ourselves”, is now banning this practice (because assuming that they would just use common sense was apparently a bridge too far).

This practice wasn’t widespread, so this is a relatively small change that shouldn’t have much impact on the overall market.

Change #2: “OSFI is requiring lenders to enhance their loan-to-value (LTV) measurement and limits so they will be dynamic and responsive to risk.”

This change requires lenders to ensure that their LTV ratios are “reflective of risk and are updated as housing markets and the economic environment evolve.”

Here OSFI is clarifying how lenders will be expected to respond if there are price corrections in regional housing markets.

This is important because, while house prices can drop quickly, mortgage balances decline much more slowly, and that means that regional LTV ratios can change substantially after loans are made. This rule change will require lenders to “enhance” (read: lower) their LTV limits on new mortgage originations in regions that experience house price corrections until the overall LTV ratio in those areas returns to more typical levels.

Interestingly, lenders have historically limited LTV ratios in falling markets of their own accord. For example, they did this in Alberta two years ago, after the oil-price shock, giving rise to the old quip that “a banker is someone who offers you an umbrella when the sun is shining and then asks for it back as soon as it starts to rain.”

That raises the question of whether OSFI now plans to more actively manage regional LTV limits.

This change isn’t likely to have any immediate market impact because no Canadian housing market is currently experiencing a sharp drop in house prices, but if OSFI decides that lenders must cut back LTV ratios pre-emptively, that may materialize the very risk that this change seeks to mitigate.

Also, our regulators should be reminded that they can’t time markets any better than the rest of us.

Change #3: “OSFI is setting a new minimum qualifying rate, or stress test, for uninsured mortgages.”

Since the fifth round of mortgage rule changes were made last year, federally regulated lenders have had to qualify all default-insured borrowers using a stress-test rate, which today is set at 4.89%. This change means that now even uninsured borrowers will have to qualify under a stress test. Surprisingly, in some cases the new stress-test rates used to qualify uninsured borrowers will be even higher than the rate used to qualify insured borrowers. That’s because it will be derived from the greater of two rates: the regular stress-test rate of 4.89%, or the actual rate on their mortgage plus another 2%, which on many terms today is higher than 4.89%.

This last change will be the most impactful of any made since the financial crisis began because it affects the broadest swath of borrowers. To cover it in detail, I will break down my thoughts into three categories: the good, the bad and the ugly (and I sure hope that OSFI superintendent Jeremy Rudin reads the ugly part).

Uninsured Mortgage Stress Test: The Good

First, a quick review.

The rapid expansion of household debt levels in Canada has been fuelled by ultra-low interest rates that were made possible, to a significant degree, by the widespread use of federally backed mortgage default insurance.

As regulators grew increasingly concerned about our rate of household debt accumulation, they decided to make it tougher for borrowers who needed default insurance to qualify, and they also restricted the types of mortgages that were eligible for default-insurance coverage. The latter change raised lender financing costs on a wide range of mortgages and those costs were then passed on to borrowers in the form of higher rates.

After the fifth round of rule changes made in the fall of 2016, insured volumes dropped by about 5%, exactly as our regulators intended, but uninsured volumes increased by almost 20% over the same period. Many borrowers simply increased their down payments to avoid the tougher standards being applied to high-ratio borrowers (who have down payments of less than 20% of the purchase price).

Most of that shift in volume landed on the balance sheets of the major banks, who used their war chests of customer deposits to fund the increased demand for uninsured mortgages. But that alternative only existed because the rates that banks pay on deposits are ultra-low, and they are only ultra-low because our federal government insures the first $100,000 of each depositor’s funds against loss.

In other words, when mortgage default insurance became more limited, the banks simply relied on funds that came with a different kind of federal guarantee to sidestep the intended impact of the prior mortgage rule changes. I predicted that this is exactly what would happen last fall in a post I wrote about the fifth round of changes. (If you click on the link, scroll down to the picture of the boy wearing glasses.)

This change is an acknowledgement by OSFI that limiting borrower access to one source of cheap rates while leaving another untouched did not limit overall mortgage volume. In reality, it only penalized the non-bank lenders and redistributed their mortgage volumes to the federally insured banks.

So, in summary, this most recent change restores a level playing field for lenders and now accomplishes OSFI’s original intent to restrict overall borrowing.

So, in summary, this most recent change restores a level playing field for lenders and now accomplishes OSFI’s original intent to restrict overall borrowing.

On a related note, as much as the major banks have said that the non-bank lenders will feel the hardest pinch from this change, I don’t buy it. Our regulators are aiming this one straight at them and they will take the brunt.

Uninsured Mortgage Stress Test: The Bad

Until last week, our regulators had always been willing to grant increased latitude to borrowers who could put down 20% or more of the purchase price, allowing them to use longer amortization periods and to qualify at their contract rates. Now, while longer amortizations will still be available, the new low-ratio stress test will reduce the maximum mortgage amount that low-ratio borrowers can qualify for by an average of about 20% to 25%.

That said, it should also be noted that not every borrower pushes their mortgage amount to the maximum, and as such, it is estimated that this change will affect between one in four to one in six low-ratio borrowers (using a study done last year by the Bank of Canada that looked at the gross-debt service and total-debt service ratios of recent Canadian mortgage borrowers).

A reduction in affordability for a wide swath of borrowers is bound to slow borrowing, exactly as our regulators intended. That reduction also has the potential to slow house-price appreciation, or even trigger outright price declines, which may also be as our regulators intended.

In particular, this change comes at an inopportune time for the Greater Toronto Area housing market, which had already lost momentum after the introduction of the non-resident foreign home buyers tax last spring.

Uninsured Mortgage Stress Test: The Ugly

OSFI superintendent Jeremy Rudin recently told reporters that the decision to use the greater of the stress-test rate (currently 4.89%) or the actual rate on the mortgage plus another 2% was made because “we didn’t want to create an artificial incentive for borrowers to shorten term because of the regulation.”

I found this baffling. To understand why, let’s look at an example under the new rules.

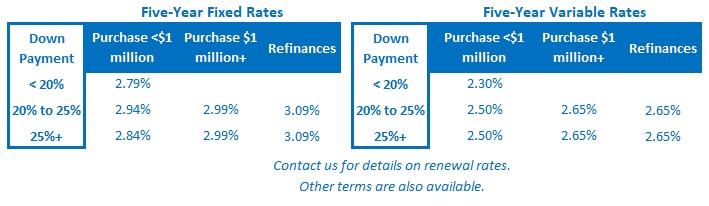

Today I can offer uninsured borrowers a two-year fixed rate of 2.79% and a five-year fixed rate of 3.09%.

If borrowers want the two-year fixed rate, then I need to use the stress-test rate of 4.89% to qualify them (because the two-year rate plus 2% is 4.79%, which is lower than the stress-test rate). If they want the five-year fixed rate, I will need to use the 3.09% plus 2%, which works out to 5.09% (because that rate is higher than the stress-test rate).

In other words if borrowers are at the upper end of their affordability, they may have no choice but to take a shorter-term fixed rate – which is exactly the opposite of what OSFI intended. And given that in normal circumstances, longer-term rates will always be higher than shorter-term rates, how did OSFI not come to the same conclusion?

Another change I found surprising was OSFI’s decision to exempt borrowers who are renewing their mortgages from the new stress-test standard as long as they are staying with the same lender.

The risk is the same regardless of who the lender is. Does OSFI really want all borrowers to be held captive by their existing lender? Why does OSFI want to make it harder for a borrower to get the best deal at renewal?

This change doesn’t improve the stability of our financial system one iota but it does serve to reduce competition. One has to wonder whether this strange anomaly is the result of some very effective lobbying by the usual suspects.

In summary, the impacts of the sixth round of mortgage rule changes will be far reaching.

As I pointed out in last week’s post, a decrease in our rate of borrowing will slow consumer spending and, because consumer spending is so important to our economy, our overall economic momentum. As that happens, the likelihood of additional mortgage rate increases in the near term will decrease.

Meanwhile, a portion of the affected mortgage volume will now flow to credit unions, which are regulated provincially and, as such, are not directly subject to OSFI’s new guidelines (although I expect provincial regulators to respond quickly if their volumes spike precipitously).

We should also see an increase in the demand for mortgage funds from other non-federally regulated lenders as these changes bifurcate our existing mortgage market. This will inevitably lead to more risk-based pricing, something that may well turn out to be a healthy long-term evolution from our traditional one-rate-fits-all mortgage market structure.

Lastly, on a related note, while many mortgage brokers have decried the latest changes, the demand for independent advice from the true experts among us will only increase as borrowers face an increasingly complex mortgage market.

The Bottom Line: The latest rule changes are intended to reduce the risk of mortgage defaults and to slow household debt accumulation. As that happens, consumer spending will slow and when it does, so will our overall economic momentum. While that may cause house prices to drop in some regional markets, it will also reduce the likelihood that we’ll see additional mortgage rate increases in the near future.