Where’s My Rate Drop?

March 20, 2023Will Strong GDP Growth Bring Higher Mortgage Rates?

April 3, 2023When central bankers cranked up their policy rates to combat runaway inflation, they knew that it would create economic pain. You can’t slow an economy that has been gorging on ultra-low interest rates for more than a decade without breaking things.

At some point, an economy must take its medicine. If tighter monetary policy doesn’t wring out the excesses that built up during the free-money era, financial markets will eventually sort out the imbalances. Odds are, that would be a much less orderly process.

The failure of weak, poorly managed banks is simply the manifestation of the pain that our central bankers warned us about. Our policy makers will do their best to limit financial contagion and other collateral damage, but only if it doesn’t interfere with slaying the inflation dragon.

Last week, the US Federal Reserve tried to strike a delicate balance between inflation and financial stability risks with its latest policy-rate decision and accompanying statement.

It hiked its policy rate by another 0.25% and altered its forward guidance. Instead of reiterating its prior warnings that financial markets should expect “ongoing increases”, the Fed assessed that “some additional policy tightening may be appropriate”.

This shift in the Fed’s forward guidance, while dovish, should not be interpreted as confirmation that it will become as accommodative as it has been over the last decade, even if financial conditions weaken further.

Rampant and sticky inflation has taken away that luxury.

This time around, the Fed’s softer language about the potential for additional rate hikes is simply an acknowledgement that the current banking crisis will be another drag on economic growth. The tighter credit conditions it has created will do much of the heavy lifting that would otherwise be left to monetary policy. (By some initial estimates, the tighter lending spreads and higher liquidity requirements that the banking crisis has brought about could end up being equivalent to another 1.50% in Fed hikes.)

Simply put, further economic tightening is still in store – but it will now take a different form.

On the brighter side, the US (and European) bank failures have been a short-term boon for Canadian mortgage borrowers.

US Treasury yields continue to plunge as bond-market investors flee to the relative safety of sovereign debt and increase their recession bets. As is typically the case, Government of Canada (GoC) bond yields have been taken along for the ride and so have the fixed mortgage rates that are priced on those yields.

The US banking crisis could also lead to lower Canadian inflation.

If the Fed stops raising its policy rate so that the gap between the Bank of Canada (BoC) and Fed policy rates doesn’t grow as wide as had been expected, the Loonie should strengthen against the Greenback. A loftier Loonie will lower the price of everything we import from US markets, causing a significant driver of inflation to morph into a new source of disinflation.

While the knock-on effects from the US banking crisis decrease the likelihood that the BoC will enact additional rate hikes, our variable-rate borrowers are probably still more interested in knowing when the Bank will start cutting its policy rate.

That will continue to depend on how domestic inflation evolves, and on that note, Statistics Canada released its latest Consumer Price Index (CPI) data last week. It showed that overall inflation increased by 5.2% in February on a year-over-year (YoY) basis, which was below both the consensus forecast of 5.4% and the 5.9% result in January.

While that big drop in our headline CPI was welcome news, most of the decline was attributed to favourable base effects, which occurred when last year’s comparative figures were particularly high.

Core inflation, which strips out the most volatile inputs to our overall CPI, fell by less last month. It came in at 4.8% YoY in February, down from 4.9% YoY in January. The BoC’s other key gauges of core inflation (CPI-median and CPI-trim) also registered only small declines.

Also of note, average wages rose by 5.4% in February, which means that wages are outpacing prices for the first time since inflation began to spike. The BoC has repeatedly acknowledged that inflation isn’t going to return to its 2% target until wage growth, and the labour demand that is causing that growth, slow considerably. So far, we haven’t seen convincing evidence of that.

In my previous inflation updates, I warned that the BoC’s ability to cool inflation will be reduced for as long as Canadian consumers are both willing and able to pay higher prices.

Practically speaking, that will require waiting it out until most Canadians have burned through most of the surplus cash that they were able to save during the pandemic.

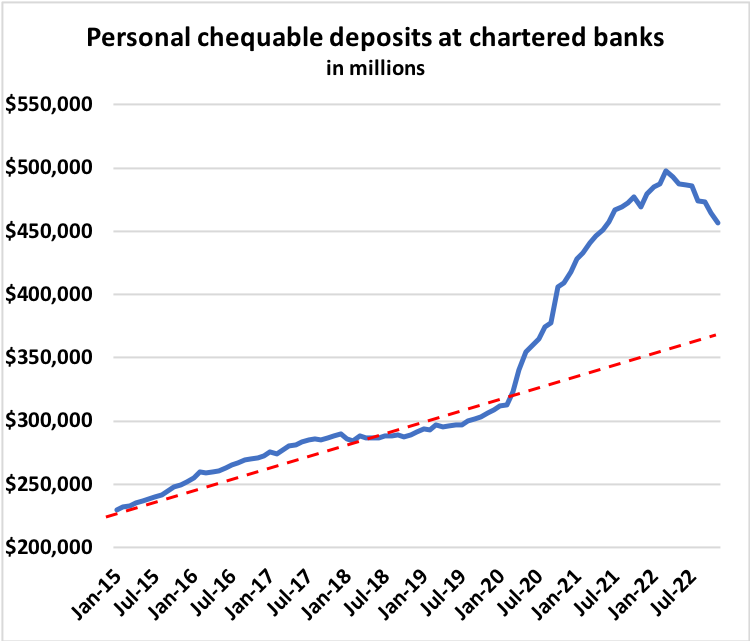

Here is an updated chart (see right), courtesy of Ben Rabidoux at North Cover Advisors, showing how those cash balances are faring.

The closer the blue line gets to the red line, the less insulated Canadians will be from higher prices, and relatedly, the more impact the BoC’s rapid series of rate hikes will have on future demand.

If you’re looking for indicators of when inflation (and demand that causes it) will really start cooling, this chart is an important one to watch. The Bottom Line: GoC bond yields fell again last week, and our fixed mortgage rates followed.

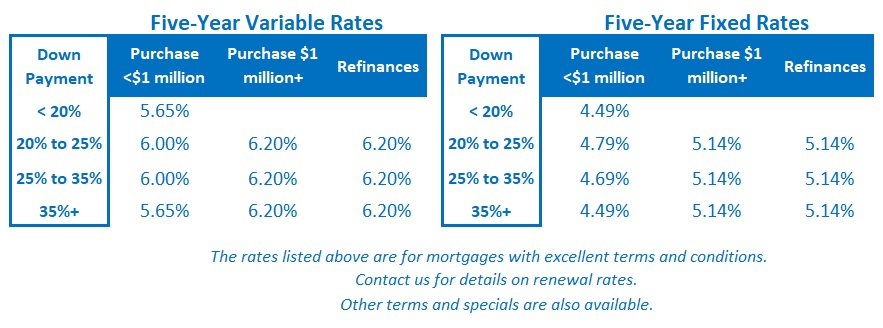

The Bottom Line: GoC bond yields fell again last week, and our fixed mortgage rates followed.

That said, the fixed mortgage rates that are insured by some form of federal-government guarantee have fallen by much more than the uninsured rates, which require investors to assume the default risk. Therefore, some fixed-rate borrowers are benefiting much more than others.

Variable mortgage-rate discounts were unchanged last week.

It is now far less likely that variable-rate borrowers will experience additional rate hikes over the near term, but it is also unlikely that any rate cuts will materialize before some time in 2024.