Words That Move Markets

October 22, 2012Canadian Household Debt Levels: Separating Fact From Fiction

November 5, 2012 When the Bank of Canada (BoC) released its latest interest-rate statement last Tuesday it did not shift to a more neutral stance on the future direction of Canadian interest rates as many were expecting.

When the Bank of Canada (BoC) released its latest interest-rate statement last Tuesday it did not shift to a more neutral stance on the future direction of Canadian interest rates as many were expecting.

Well, not quite anyway.

In its carefully worded final paragraph, the BoC closed with the following statement:

“Over time, some modest withdrawal of monetary policy stimulus will likely be required, consistent with achieving the 2 per cent inflation target. The timing and degree of any such withdrawal will be weighed carefully against global and domestic developments, including the evolution of imbalances in the household sector.”

Here is what was noteworthy in that statement:

- The phrase “over time” is new, and it implies a longer time horizon for future rate increases.

- The BoC’s June interest-rate statement included the phrase, “To the extent that the economic expansion continues and the current excess supply in the economy is gradually absorbed, some modest withdrawal … may become appropriate.” No mention of the economy needing to be operating above potential to trigger rate increases this time around.

- Instead, the BoC appears to have shifted its focus with the phrase, “The timing and degree of any such withdrawal will be weighed carefully against … the evolution of imbalances in the household sector.”

That is the first time the BoC has mentioned household debt levels in its always-studied-under-a-microscope closing statement. Governor Carney has been talking about the risk of our record and still rising debt levels for some time but he has always acknowledged that monetary policy is a less-than-ideal tool for fixing this problem. In the Governor’s own words, monetary policy is the “last line of defence” against runaway debt.

Here is a little more background on how we got to this point and why Governor Carney remains reluctant to raise rates to reign in consumer borrowing:

- When the Great Recession started the BoC lowered its overnight rate to emergency levels in the hopes that businesses would take advantage of cheaper borrowing costs and invest in productivity improvements. (Canadian productivity levels have lagged behind those in the U.S. for many years and Governor Carney saw this as an opportune time for businesses to take advantage of both the strong Canadian dollar and our ultra-low borrowing rates to invest in productivity improvements.)

- But the same low interest rates that were supposed to stimulate business spending were also available to consumers – who took full advantage.

- In the end, increased consumer spending did much more to help the economic recovery than expanded business investment. But whereas business balance sheets were well positioned to take on additional debt, household balance sheets were already highly leveraged.

- Governor Carney understood that while this surge in consumer borrowing rates provided much needed short-term economic stimulus, it was also adding substantial systemic risk because it led to record household debt levels and rapid house price appreciation across the country.

- To fix the problem himself, Governor Carney would have to raise interest rates, but this would invoke powerful negative side effects. Specifically, it would raise the cost of borrowing for both businesses, at a delicate stage of their recovery, and for over-leveraged consumers. It would also push the price of the Canadian dollar to new heights and raise the cost of our exports, heaping more suffering on our already hard-hit manufacturing sector. (On that last point, Governor Carney acknowledges that the Canadian dollar now includes a price premium because it is seen as a “safe-haven currency”. You can just imagine the impact that raising our interest rates at a time when the rest of the world is lowering theirs would have on our already-in-high-demand-Loonie.)

- Thus, with only a blunt instrument to fix a problem that required a carefully targeted solution, Governor Carney publicly implored Federal Finance Minister Jim Flaherty to use his better suited regulatory policy tools to reign in household borrowing.

- But unlike the BoC Governor, Minister Flaherty has to run for re-election and after making several rounds of changes to the underwriting rules used for high-ratio mortgage insurance, he is increasingly reluctant to keep trying his luck with more credit tightening. (If he pushes too hard, his interventions might be seen to have exacerbated any ensuing market corrections. This would probably be unfair, but in politics that’s cold comfort.)

- So instead of actually raising rates, Governor Carney seems to be trying to do everything but. At the very least, he has quashed any bond-market speculation that the BoC overnight rate might be lowered and he seems to have made consumers less thirsty for the borrowing punch bowl. (The BoC estimates that our consumer-borrowing growth rates have been running at about 5.5% since the beginning of the year, compared to our long-run average of a little less than 8%.)

Here are some other highlights from the BoC’s full Monetary Policy Report (MPR), which I always read with great interest:

International Economic Commentary

- The U.S. recovery is progressing “at a gradual pace”, indicators in Europe “point to a continued contraction” and in China, “growth has slowed somewhat more than expected … though there are signs of stabilization”.

- Estimates for global growth were left largely unchanged (slight -.1% revision to 2012) but the BoC’s base-case scenario assumes that “the crisis in the euro area will remain well contained” and that “a severe tightening of U.S. fiscal policy … will be avoided”. For my money, that leaves some gaping-sized wiggle room in their numbers.

- “Relative to the July [MPR] Report, U.S. GDP growth in 2013 and 2014 has been revised up to 2.3 per cent and 3.2 per cent, respectively, owing to a larger policy response by the Federal Reserve than was previously expected.” I am not nearly as convinced that QE3 will lead to higher growth rates. In my opinion, the U.S. Fed’s quantitative easing programs have reached the point where they are pushing on a proverbial string.

- “Excess supply in the U.S. economy is expected to remain significant until well beyond 2014, dampening underlying inflationary pressures.” I have long maintained that deflation, not inflation, poses the greater threat to the U.S. economy.

Canadian Economic Commentary

- GDP growth estimates of 2.1% in 2012, 2.3% in 2013, and 2.5% in 2014 from the July MPR were raised slightly by .1% in 2012 and .1% in 2014.

- Core inflation is now expected to reach 2% ”by the middle of 2013” and total CPI inflation, which “has fallen noticeably below the 2 per cent target” is expected “to return to target by the end of 2013”. Both revisions pushed the timing of inflation increases farther into the future.

- The BoC now expects the economy to return to full capacity “by the end of 2013” (versus the Bank’s mid-2013 estimate in the July MPR).

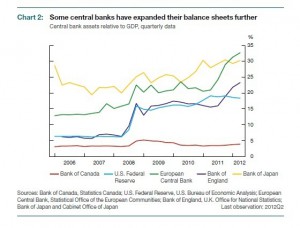

- I couldn’t resist sharing this graph from page 4 of the October MPR. If you have ever wondered why our bond yields have been at record low levels for so long, and why the Loonie has traded at or above-par with the Greenback for some time now, look no further. (Well played Governor Carney.)

- And in a related point: “The Canadian dollar has averaged 101 cents U.S. since the July Report, higher than the 98 cents U.S. assumed in July … and is assumed to average 101 cents U.S. over the projection horizon.”

- The BoC estimates that the U.S. Federal Reserve’s implementation of QE3 will be “modestly positive for the Canadian economy, lifting the level of real GDP by about 0.4 per cent by 2014.”

- “Growth in consumption is thus expected to be moderate over the projection horizon … the measures implemented in recent months by federal authorities are expected to contribute to a more sustainable housing market in Canada.”

Five-year GoC bond yields were 2 basis points higher for the week, finishing at 1.39% on Friday. Five-year fixed rates are still widely available in the 3% range.

Variable rates can still be found with discounts in the prime minus 0.40% range (which works out to 2.60% using today’s prime rate).

The bottom line: Last week I speculated that if the BoC didn’t soften its interest-rate guidance to a more neutral position, it would be because the Bank is still worried about rising household debt levels and not because it really thinks rates are likely headed higher any time soon. That still reads about right to me.