The Bank of Canada Pushes Back on Bond-Market Expectations

April 17, 2023Should Canadians Reconsider a Variable-Rate Mortgage?

May 1, 2023 Last week Statistics Canada confirmed that our Consumer Price Index (CPI) dropped to 4.3% in March on a year-over-year basis, down from 5.2% in February and well below the peak of 8.1% we saw last June.

Last week Statistics Canada confirmed that our Consumer Price Index (CPI) dropped to 4.3% in March on a year-over-year basis, down from 5.2% in February and well below the peak of 8.1% we saw last June.

That rapid inflation drop has mostly been caused by base effects. Here is a quick review of Stats Can’s definition of this phenomenon:

A base-year effect refers to the impact that price movements from 12 months earlier have on the current month’s headline consumer inflation. When a large 1-month upward price change in the base month stops influencing or falls out of the 12-month price movement, this has a downward effect on headline CPI in the current month.

Put more simply, inflation is dropping because prices that spiked a year ago are aging out of the CPI basket.

The dramatic impact from base effects will carry into the summer months, and both the BoC and the bond market expect inflation to be hovering in the 3% range by the time they wear off.

When we reach that point, the calls for rate cuts will grow louder.

Pundits will claim that inflation has been vanquished and that Canadians need rate relief. They will rightly add that while the BoC has a target of 2% inflation, its mandate allows for a broader inflation band of 1% to 3% to give it flexibility to manage through short-term turbulence.

We should also expect analysts to question whether strict adherence to an arbitrary 2% target makes sense anyway, especially given that a material portion of today’s inflation pressure is being caused by higher borrowing costs, which are largely of the BoC’s own making. (Higher mortgage interest costs accounted for 0.8% of our 4.3% CPI increase last month.)

One could argue that an inflation target of 3% would be more appropriate at a time when we are experiencing deglobalization, when our working-age population is shrinking relative to our total, and when our government and household debt levels are at record highs. (It’s no secret that inflating some of today’s debt away would be more politically palatable than the messy business of paying it all back.)

But the BoC is already laying down its counter argument.

As I noted in last week’s post, BoC Governor Macklem keeps reminding Canadians that “the destination is not 3, the destination is 2” and that the Bank won’t be contemplating rate cuts until inflation falls all the way to that level. He has also warned that “we are prepared to raise the policy rate further” if today’s rates aren’t restrictive enough to complete the job.

Although 3% may seem close to 2%, rates aren’t like horseshoes or hand grenades. Getting from 3% to 2% is going to take quite some time. Wages are still rising at about 5% year-over-year and we won’t have the same strong base-effect tailwind at our backs in the second half of this year.

The BoC’s stubborn stance does, however, make sense in one way.

It is as concerned about inflation expectations as it is about actual inflation because expectations can become self-fulfilling prophecies. We are seeing this play out in real time with the strike of 155,000 federal public-sector workers. They are demanding pay increases that will allow them to recover both the purchasing power they have lost to inflation thus far and the purchasing power they anticipate losing over the life of their next union contract.

But the Bank is also talking itself into a corner.

The 1% to 3% inflation band exists because setting the appropriate policy rate involves more than just dogmatic adherence to a 2% inflation target. The Bank might have wanted to use that flexibility as the lagged impact of its 4.25% in rate hikes plays out, but it has now effectively undermined that option with its current rhetoric.

The BoC’s vital credibility was damaged in 2020 when Governor Macklem told Canadians to expect rates to stay low for a long time, adding that the Bank didn’t anticipate its first rate hike until the second half of 2023.

To dig in again now, near the rate peak, after the Bank got it so wrong last time, severely limits its flexibility going forward.

The BoC is forecasting a soft landing for our economy, where inflation falls without the need of a deep recession. But that doesn’t seem likely after the sharpest series of rate hikes that we have seen in more than four decades, and with a bond-yield curve that has inverted to a level that has been followed by a recession 100% of the time in the past.

The Bank better hope its forecast proves correct, because if things don’t go as planned (and they rarely seem to these days), it will then have to choose between severe economic pain for Canadians or a second hard hit to its credibility. The Bottom Line: Government of Canada bond yields continued to rise early last week before reversing course on Thursday, leaving us a little lower for the week by close of business on Friday.

The Bottom Line: Government of Canada bond yields continued to rise early last week before reversing course on Thursday, leaving us a little lower for the week by close of business on Friday.

That should keep fixed mortgage rates range bound, for now.

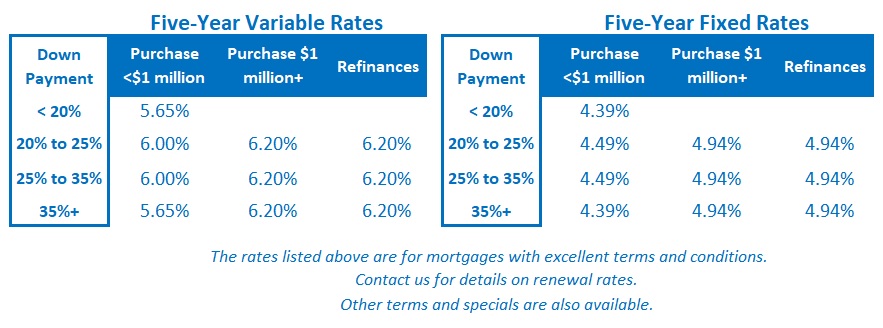

Five-year variable-rate discounts were unchanged last week. The bond market continues to price in at least one BoC rate cut by the end of 2023. For the reasons outlined above, I still think we’ll be waiting until the second half of 2024 before we see that happen.