Canadian Wage Growth Decelerates Again

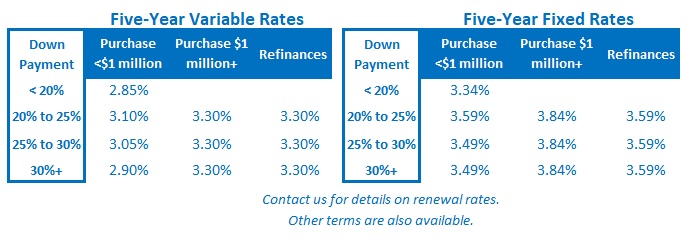

November 5, 2018Fixed vs. Variable: Is the Five-Year Fixed-Rate Mortgage Now a No Brainer?

November 19, 2018 The Bank of Canada (BoC) recently warned that higher interest rates will likely be required to keep inflation near to its 2% target. That view, however, is underpinned by what many consider to be an optimistic assessment of our current economic trajectory.

The Bank of Canada (BoC) recently warned that higher interest rates will likely be required to keep inflation near to its 2% target. That view, however, is underpinned by what many consider to be an optimistic assessment of our current economic trajectory.

The Bank is predicting that accelerated business investment, increased demand for labour and resilient consumer spending will push our economy closer to its maximum capacity and fuel rising inflationary pressures. That said, the BoC also insists that it will be guided by the incoming data, and if that’s true, one wonders what data it is seeing that so many others, myself included, are missing.

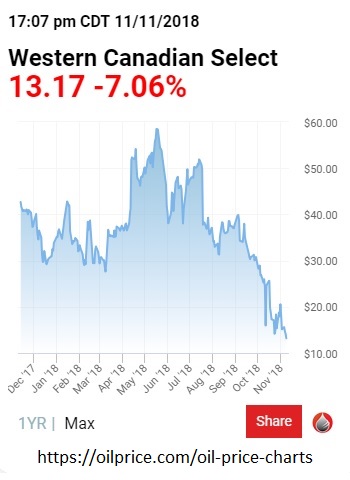

In the most glaring example, consider that oil prices have fallen precipitously of late. The price of a  barrel of West Texas Intermediate has fallen from $72 in May to $60 in today. That’s bad enough, but consider that a barrel of Alberta’s Western Canadian Select (WCS) that sold for $58 in May now sells for about $13.

barrel of West Texas Intermediate has fallen from $72 in May to $60 in today. That’s bad enough, but consider that a barrel of Alberta’s Western Canadian Select (WCS) that sold for $58 in May now sells for about $13.

In a recent report, CIBC Chief Economist Avery Shenfeld noted that today’s WCS price is now well below the levels it fell to in 2015 when the BoC responded with two 0.25% emergency policy-rate cuts (the price bottomed out at $22/barrel in January 2016). Shenfeld predicts that the “the oil sector – responsible for Canada’s largest export product as well as up to a third of business capital spending in good times – will be reverting to a drag on growth forecasts in upcoming quarters.”

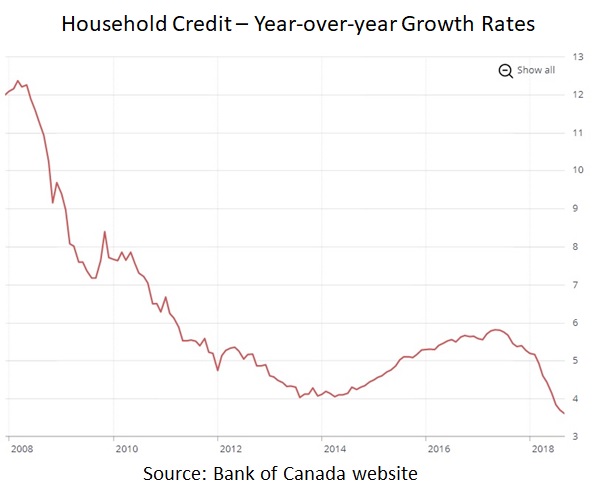

Economist David Rosenberg recently offered other examples of weakness in our data. Last week, he noted that year-over-year household credit growth slowed to 3.6%, marking a 35-year low, and that “this is before the lagged effects of the prior rate hikes have been fully felt!” Against that backdrop, auto sales have declined for eight straight months on a year-over-year basis.

Economist David Rosenberg recently offered other examples of weakness in our data. Last week, he noted that year-over-year household credit growth slowed to 3.6%, marking a 35-year low, and that “this is before the lagged effects of the prior rate hikes have been fully felt!” Against that backdrop, auto sales have declined for eight straight months on a year-over-year basis.

He also highlighted recent softness in our manufacturing data, pointing to elevated inventory levels, which have led to “particular weakness in the forward-looking new orders index which points to a meaningful loss of momentum heading into the fourth quarter”.

In my post last week I noted that our recent employment data have not matched the BoC’s bullish rhetoric either. Consider that our average year-over-year wage-growth rate has now fallen for five straight months and that our October result, of 1.9%, was below our current inflation rate of 2.2%. (That means that the average wage earner’s purchasing power shrank last month – and that’s not a good omen for consumer spending.)

While our current unemployment rate of 5.8% matches the lowest it has been in forty years, it doesn’t count people who have given up looking for work. Our participation rate, which measures the percentage of working-age Canadians who are either working or actively looking for work, fell to 65.2% in October. That result is well below its long-term average, and it continues a steady decline that has been years in the making.

One can reasonably infer that our falling participation rate gives our economy more labour capacity than our official unemployment rate otherwise implies. BoC Governor Poloz acknowledged this in a speech he made earlier this year when he estimated that there may be up to one million working-age Canadians currently on the sidelines. Strangely, he hasn’t reconciled that statement with the Bank’s growing concerns about labour shortages, which appear to be based in part on business surveys showing a rise in hiring intentions that may or may not ultimately materialize.

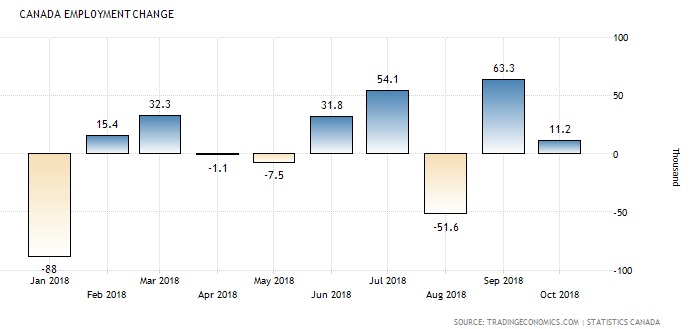

Our year-to-date job-creation data haven’t been all that exciting. Consider that our economy has added only 59,900 net new jobs thus far in 2018, or an average of 5,990 new jobs per month (see chart below). That number barely puts a dent in the million workers that the BoC believes may be waiting in the wings.

It’s hard for me to reconcile the BoC’s bullish view in the face of the hard data I have outlined above, especially when combined with ongoing trade uncertainty, signs of slowing U.S. economic momentum, and instability risks from the Italian bond-market’s convulsions, from Brexit, and from China’s sharp economic slowdown. All of that leads me to wonder, only half facetiously, if the BoC’s optimistic outlook includes a very bullish forecast for the impact that cannabis legalization will have on our economic momentum (which the BoC noted was not incorporated into its latest Monetary Policy Report).

The Bottom Line: The BoC continues to signal that it expects to hike its policy rate again soon, and fixed mortgage rates rose again last week as the Government of Canada bond yields they are priced on moved higher in anticipation of that outcome. That said, for the reasons outlined above, I don’t think our current economic data support additional near-term policy-rate increases. Unless a new catalyst emerges to spur our growth higher (ahem), the Bank’s plans may well go up in smoke.