Is It Time for Variable-Rate Borrowers to Lock In?

November 15, 2021Bond Yields Plunge in Response to New Outbreak Threat

November 29, 2021 Last Wednesday Statistics Canada confirmed that our overall Consumer Price Index (CPI) hit 4.7% in October on a year-over-year (YOY) basis.

Last Wednesday Statistics Canada confirmed that our overall Consumer Price Index (CPI) hit 4.7% in October on a year-over-year (YOY) basis.

That result marked our highest inflation rate in nearly twenty years but the bond yield surge that followed was nevertheless short lived.

The five-year Government of Canada (GoC) bond yield which our fixed mortgage rates are priced on finished the week lower than where it had started.

There were several reasons for this.

For starters, the week before we learned that the US CPI hit 6.2% in October, and a 4.7% increase seems downright boring by comparison. And as high as last month’s result was, it was directly in line with the consensus estimate, and with the BoC’s forecast for Q4, which also means it didn’t come as a surprise.

More importantly, though, the price increases that underpin our current CPI runup are attributable to temporary factors that are unlikely to fuel sustained increases. For example:

- Energy prices (+26% YOY) are notoriously volatile and have been driven higher by supply shortages, most notably gasoline prices (+42% YOY). At some point, both capacity and availability will increase and these prices will moderate. (In the meantime, if we exclude last month’s energy-price spike, the rest of our overall CPI basket would have risen by a more palatable 3.3% YOY.)

- Meat prices (+10% YOY) are being impacted by a combination of supply and labour shortages and by rising livestock feed prices affected by ongoing drought conditions. All three of these factors will eventually be resolved.

- Used car prices (+6.1% YOY) are being driven higher by a temporary shortage of semi-conductor chips.

While we’re on the topic, another transitory factor may be about to become the most significant of them all.

Flooding in British Columbia’s lower mainland has just led to the closure of our country’s largest port, the Port of Vancouver, to all rail-bound traffic. This will crimp the supply of goods across our economy and put more near-term upward pressure on a wide range of prices. (I must add, that those price increases are small inconveniences when compared to the suffering of the Canadians who have been directly impacted.)

Last week, in an opinion piece in the Financial Times, Bank of Canada (BoC) Governor Tiff Macklem reiterated the Bank’s belief that “recent inflation dynamics are transitory” and he continued to push back against the bond market’s bet that surging inflation will force it to start raising rates before our economy’s slack is fully absorbed.

As dramatic as our recent inflation run-up has been, we should remember that, when averaged together, the BoC’s three core measures of inflation remain within their target band of 1% to 3% and that the Bank’s most preferred measure, CPI-common, came in at 1.8% last month (and still hasn’t exceeded 2% at any point during the pandemic).

Transitory factors aside, the real test of where inflation and mortgage rates are headed over the longer term will come down to wages.

In a speech last Tuesday, BoC Deputy Governor Lawrence Schembri outlined the challenges in measuring the strength of our current labour market. He also highlighted several areas of concern and reiterated the Bank’s commitment to holding its policy rate steady until our labour market recovery is complete.

Interestingly, in his accompanying Q & A session, Schembri pushed back against the bond market’s belief that the BoC’s first rate rise will come early next year. He told listeners to “be careful not to assume it’s necessarily going to be the second quarter” before adding, “it’s a range of six months. That’s our best estimate.”

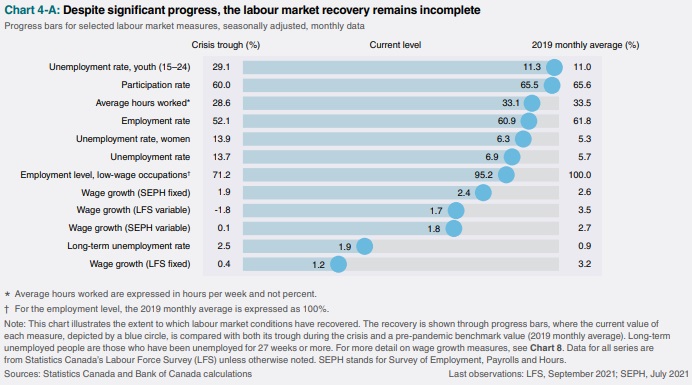

If you’re wondering where that caution stems from, this chart from the Bank’s latest Monetary Policy Report (MPR) summarizes our current labour market conditions relative to their pre-pandemic levels. (I am highlighting it again because sometimes a picture does speak a thousand words.)

Inflationists should note that our wage growth lags by more than any other measure. From my desk, it sure looks as though the BoC is telling anyone who is still listening not to get too far over their ski tips on the rate-hike theme. (Right now, the bond market is pricing in five quarter-point rate hikes next year, with the first one coming next March and a total of seven by the end of 2023.)

From my desk, it sure looks as though the BoC is telling anyone who is still listening not to get too far over their ski tips on the rate-hike theme. (Right now, the bond market is pricing in five quarter-point rate hikes next year, with the first one coming next March and a total of seven by the end of 2023.)

In summary, today’s inflationary pressures are still mostly attributable to supply shortages tied to the pandemic, droughts and, starting now, flooding. Rate hikes won’t alleviate any of those challenges, and using them to kill demand would simply compound our short-term problem (supply) with a longer-term problem (growth).

There is, in fact, a far better option on the table, as Globe and Mail writer David Parkinson astutely pointed out last week.

He suggested that if we’re looking to ease temporary inflation pressures without inflicting more lasting damage to our long-term momentum, our federal government should curtail the $100 billion in pandemic-related stimulus spending that it has allocated over the next three years but not yet spent. Doing so would help “address the demand pressures that it is helping to fuel”.

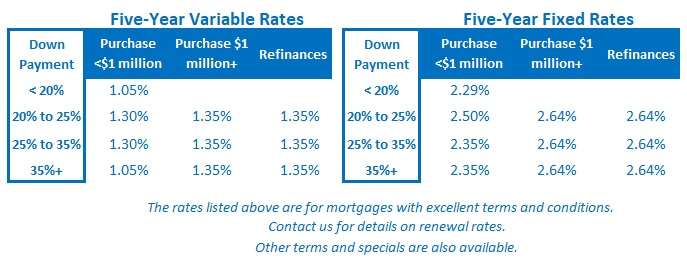

(Behind closed doors, I suspect the BoC has given that same advice to our federal government more than once.) The Bottom Line: Five-year GoC bond yields shrugged off the latest Canadian inflation data last Wednesday, leaving our five-year fixed mortgage rates unchanged – but given their steady increases of late, they retain an upward bias.

The Bottom Line: Five-year GoC bond yields shrugged off the latest Canadian inflation data last Wednesday, leaving our five-year fixed mortgage rates unchanged – but given their steady increases of late, they retain an upward bias.

Five-year variable rates held steady again last week, preserving their large discount from fixed rates, and the BoC’s recent commentaries reinforce my belief that the bond market’s bet on five hikes in 2022, with the first one in March, is far too aggressive.