Falling U.S. Bond Yields Will Probably Push Canadian Mortgage Rates Lower

October 7, 2019Why Are Canadian Fixed Mortgage Rates Rising Again?

October 21, 2019 Recent U.S. economic data portend a slowdown that could work its way north of the border.

Recent U.S. economic data portend a slowdown that could work its way north of the border.

Despite this, some market watchers speculate that the Bank of Canada (BoC) will delay cutting its policy rate for fear that it will fuel increased borrowing and accelerate house-price appreciation (which has picked up on its own lately).

This theory is fundamentally flawed for two reasons:

- A BoC rate cut only affects variable mortgage rates, and few borrowers are opting for variable rates in the current environment.

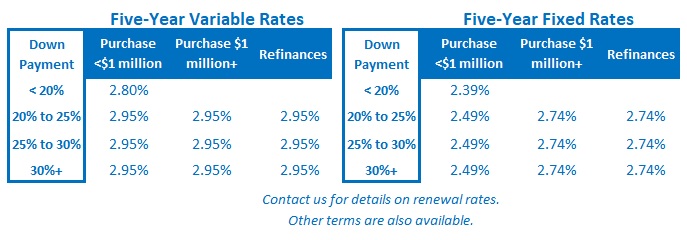

The Canadian yield curve is still inverted, meaning that short-term interest rates are higher than longer-term interest rates, and as such, just about everyone is opting for fixed rates now. Consider that today, the average five-year variable mortgage rate is priced about 0.50% higher than its five-year fixed-rate equivalent.

Given that gap, current variable rates won’t be remotely attractive to most borrowers at least until the BoC has made its third 0.25% cut from today’s levels. The vast majority of borrowers aren’t likely to take on variable-rate risk without receiving an initial discount to the available fixed-rate alternatives.

- A BoC rate cut isn’t going to increase borrowing capacity.

Canadian mortgage borrowers are qualified at either the current stress-test rate of 5.19%, or the greater of the stress-test rate and their contract rate plus 2%.

The stress-test rate is the arithmetic mode of the Big-Six Banks’ posted five-year fixed rates, which don’t move with any rhyme or reason and are not tied to the BoC’s policy rate. (To wit, five-year fixed mortgage rates have fallen by about 1% during the past twelve months, and over that same period, the stress-test rate fell by only 0.15%.)

At the same time, five-year fixed rates are widely available at less than 3% so it is unlikely that any prime borrower’s five-year contract rate plus 2% will be higher than today’s stress-test rate.

Taken together, these factors mean that even multiple BoC rate cuts would have no impact on anyone’s cost of borrowing and/or their capacity for borrowing.

That said, there are other reasons why the Bank may be reluctant to cut its policy rate – even if our economic data otherwise imply that it should.

For starters, the BoC isn’t too far above a policy rate of 0% (otherwise referred to as the zero bound).

The policy rate is our central bank’s most effective lever for keeping our economy from running too hot or too cold. If it is lowered to 0%, as happened during the financial crisis in 2008, its power is greatly reduced. If the BoC needs to stimulate our economy beyond that point, it would have to resort to unconventional monetary policies, such as quantitative easing.

Such policies are largely experimental and as such, their impacts are not yet fully understood. For that reason, the BoC is likely to be instinctively more cautious about cutting rates as it approaches the zero bound.

Perhaps even more importantly, rate cuts just aren’t having as much impact anymore. They are supposed to provide economic stimulus, but their boost has been dulled by years of ultra-low interest rates and bloated debt levels that have already brought forward a lot of future demand.

If the BoC is worried that additional rate cuts would reduce its future leverage, and if it also believes that rates cuts have lost much of their stimulative power in the current environment, it may decide to hold its policy rate steady for longer than it otherwise would.

While we’re on the topic, there is one other point worth reiterating for anyone hoping for the next BoC rate cut to finally arrive.

The last two occasions when the Bank cut its policy rate, by 0.25%, back in 2015 during the global oil-price collapse, lenders only passed on 0.15% discounts to variable-rate borrowers. At the time, lenders explained their decision by saying the heightened uncertainty that led the BoC to cut its rate also raised their funding costs, and they were simply passing those increased costs on to borrowers.

The same justification could potentially be used to reduce or eliminate any additional variable-rate cuts this time around. The Bottom Line: The theory that the BoC won’t cut its policy rate if our economy weakens for fear that it will fuel increased borrowing and accelerate house-price appreciation is unfounded because a) it will only lower variable mortgage rates, which almost no one is taking today, and b) because it will have no impact on the stress-test rate, which is used to determine each borrower’s maximum affordability.

The Bottom Line: The theory that the BoC won’t cut its policy rate if our economy weakens for fear that it will fuel increased borrowing and accelerate house-price appreciation is unfounded because a) it will only lower variable mortgage rates, which almost no one is taking today, and b) because it will have no impact on the stress-test rate, which is used to determine each borrower’s maximum affordability.

The BoC will have valid reasons to delay rate cuts if our economy weakens, as outlined above, but they aren’t likely to include the ones that market watchers are fond of citing at the moment.