Why Our Latest GDP Data Make the Bank of Canada’s Latest Forecast Seem Bullish

May 6, 2019Five Inflation Highlights with Implications for Canadian Mortgage Rates

May 21, 2019 Last week Bank of Canada (BoC) Governor Poloz called for more innovation in the Canadian mortgage market. He specifically targeted three key areas where innovation is needed, with longer-term mortgages topping his list.

Last week Bank of Canada (BoC) Governor Poloz called for more innovation in the Canadian mortgage market. He specifically targeted three key areas where innovation is needed, with longer-term mortgages topping his list.

In today’s post I’ll outline why longer-term mortgages have historically had limited appeal for both borrowers and lenders in Canada, and I’ll offer a suggestion to Governor Poloz on how he can facilitate a dramatic increase in the uptake of already available ten-year fixed-rate terms.

First, a confession.

When we bought our house back in 2003, my wife and I chose a ten-year fixed-rate mortgage. The 3.85% rate was about 0.75% higher than the best available five-year fixed rate at the time, but it was also well below the average five-year fixed rate over the preceding decade. (And back then the financial crisis that pushed mortgage rates to today’s rock bottom lows was still five years away.)

My priority was securing a long-term rate that we knew we could afford if we needed to live on one income. To be clear, we didn’t choose the ten year because we were convinced that it would save money; we took it because we were financially conservative and we were willing to pay an additional cost for added safety.

Rates didn’t ultimately rise and we ended up breaking that mortgage at the five-year mark because once you get beyond that anniversary date, lenders can only charge a penalty of three months’ interest (thank you Section 10 (1) of the Interest Act). We then refinanced to a five-year variable-rate mortgage because by that point, we valued saving over safety. Different life stage; different choice.

In hindsight, the ten-year fixed rate cost us some money, but while it might seem strange to some readers of this blog, I still didn’t regret the decision. We essentially paid for rate insurance that we didn’t end up needing. Sure rates didn’t go up over the ensuing five years, but we would have been well protected if they had.

As my dad said at the time, “It’s not like you buy fire insurance and then sit there wishing that your house will burn down in order to justify the expense.”

So why don’t more borrowers look at the ten-year fixed rate this way?

In my experience, the ten-year fixed rate is appealing to first-time buyers when they first start looking for a property. But once they actually buy and the realities (and costs) of home ownership set in, those same borrowers opt for the cheaper five-year fixed rate 99% of the time.

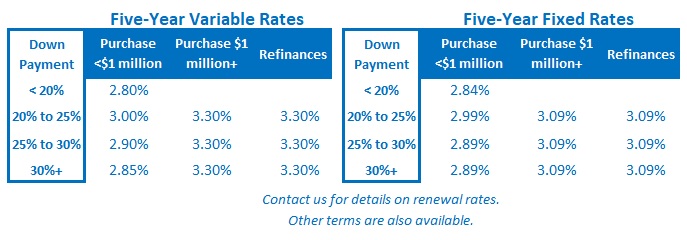

I think it’s as simple as not wanting to start with a higher mortgage payment (today’s five-year fixed rates are around 3% whereas ten-year fixed rates are around 3.5%). There certainly is logic to keeping the payment lower when the mortgage is at its largest.

But, as with most risk/reward trade offs, if the risk hasn’t materialized in a long time and if rates haven’t swung materially higher for more than twenty-five years and counting, opting for the reward becomes increasingly easier to rationalize.

Lenders don’t love fixed-term rates of longer than five years either. Here’s why:

- As mentioned above, the Bank Act requires lenders to drop their prepayment penalty to only three months’ interest once borrowers pass the five-year mark on any mortgage term longer than five years (and the Big Five banks love charging sky-high fixed-rate mortgage penalties). This dramatic reduction in the prepayment penalty increases the risk that borrowers will break their longer-term mortgages if rates don’t rise over their first five years (as happened in my case), and that reduces their appeal to lenders.

- Most Canadian mortgages are funded with deposits that come largely from chequing and saving accounts, which are tied to short-term rates. When lenders use those funds to offer longer fixed mortgage terms, they are required to hedge the interest-rate risk of the mismatch between their borrowing and lending terms. The longer the term, the greater the hedge cost. On really long-term mortgages, by the time the lender is sufficiently hedged, the rate is no longer appealing to borrowers. (Would you buy a twenty-five year fixed rate at 5% today?) Realistically, to make longer-term mortgages more mainstream, our banking regulator would need to reduce its hedging requirements to make the associated funding costs more manageable. But of course, while doing this would give lenders room to offer more attractive rates, it would also require them accept more risk.

- Instead of using deposits, lenders can fund their mortgages by selling longer-term mortgage-backed securities (MBSs), but unlike in the U.S., there is very little liquidity for MBS terms longer than five years in the Canadian market. An illiquid market increases the cost of this option – if lenders can find the market appetite at all. Governor Poloz hopes that a private, non-government-backed MBS market will develop to help fill this void.

For the reasons outlined above, I don’t think BoC Governor Poloz will see his wish of twenty-five or thirty-year fixed-term mortgages coming to Canada any time soon but if he’d settle for a substantial increase in the number of borrowers opting for the ten-year fixed rate, he can help make that happen.

Governor Poloz can simply call our Minister of Finance, Bill Morneau, and encourage him to drop the stress test for borrowers who apply for a ten-year fixed rate.

To quickly review, the mortgage stress test requires lenders to qualify borrowers using either the Mortgage Qualifying Rate (MQR) or their mortgage rate plus 2%. This tougher standard is designed to ensure that borrowers can afford to pay higher rates when their mortgages come up for renewal.

But the ten-year term does that naturally by virtue of its length. It just doesn’t make sense to add a stress test on top which makes it harder to qualify for ten-year fixed rate than a five-year fixed-rate.

If Governor Poloz thinks that our economy will be better protected if borrowers choose longer-term mortgages (and I don’t see the regulators arguing against that point), dropping the stress test on ten-year fixed rate terms would likely bring that about. Also, since doing this would funnel marginal borrowers who couldn’t pass the stress test into ten-year fixed-rate terms, this change would offer additional interest-rate protection directly to the borrowers who need it the most.

The Bottom Line: BoC Governor Poloz is encouraging mortgage lenders to be more innovative because he believes that longer-term mortgages will help mitigate risks for both borrowers and lenders. If he wants this idea to get immediate traction, the quickest way is to eliminate the stress test for ten-year terms. Doing this would help funnel marginally qualified borrowers, who are the most vulnerable to higher rates at renewal, into a longer fixed-rate term and thereby naturally reduce this danger.