The Case for Lower Canadian Mortgage Rates

March 11, 2019The New Bank of Justin and Bill

March 25, 2019 Canadian mortgage rates look a lot different today than they did only a few short months ago.

Canadian mortgage rates look a lot different today than they did only a few short months ago.

Last October, the Bank of Canada (BoC) had just completed its fifth 0.25% policy-rate increase in a little over a year, and variable-rate mortgage borrowers, who before then had enjoyed more than seven years without a single rate hike, were having their conviction tested.

The BoC had just cautioned that if it was going to keep inflation close to its 2% target, it would need to continue raising its policy rate to its neutral-rate range of between 2.5% and 3.5%. (The neutral range is defined as the policy-rate level that neither stimulates nor restricts economic growth.)

Mainstream economists predicted that sharply higher rates were imminent and argued about whether three or four more rate hikes were likely in 2019. This spooked many variable-rate borrowers, and some of them rushed to lock in a fixed rate before variable rates rose even higher.

Regular readers of this blog might remember that all of this angst got my contrarian itch going. When the BoC raised its policy rate in October, I challenged its rationale, arguing that the Bank’s own forecasts of slowing GDP growth both at home and abroad made it unlikely that inflationary pressures would intensify. Then in November, in a post titled Fixed vs. Variable: Is the Five-Year Fixed-Rate Mortgage Now a No Brainer?, I argued in favour of variable mortgage rates and predicted that “the BoC’s actions will not match its words over the near term”.

Fast forward to today.

Our economic data have continued to weaken. Our GDP growth rate came in at only 0.4% on an annualized basis in the fourth quarter of 2018, well below the consensus call of 1.2%. Our overall inflation rate slowed sharply to 1.4% in January, and the BoC’s three core sub-measures of inflation have also been trending downwards of late. Job growth has been stronger than expected, but while average wage growth recently perked up a little, it is still barely outpacing overall inflation. More importantly, weaker-than-expected business investment and exports portend softer employment data in the months ahead.

The “decidedly data dependent” BoC has sounded much more dovish of late, and given that, now seems like a good time to revisit the age-old comparison of a fixed rate versus a variable rate using our current backdrop.

The futures market is currently betting that the BoC will likely remain on hold for all of 2019 and that its next move is more likely to be a cut instead of a raise. That view is based on five key themes that emerged from the Bank’s recent commentary:

- Global economic momentum is slowing.

- Our economic slowdown has been sharper than expected.

- Housing and consumption have slowed, and business investment and exports haven’t picked up the slack as the BoC had hoped.

- Inflation expectations have been lowered.

- Overall uncertainty is increasing.

Thus far, the BoC has only conceded that it faces “increased uncertainty about the timing of future rate increases” and that it will need time to properly assess the factors that are causing our growth to slow. That language implies only a pause before the Bank resumes hiking. But experienced market watchers know that the BoC tends to shift its policy-rate view incrementally, and that’s why they are interpreting its increasingly dovish language as a precursor to eventual rate cuts.

If choosing a variable-rate mortgage sounds like a slam dunk in the current environment, it’s not.

In addition to weighing individual factors such as the ability to manage payment increases and one’s psychological tolerance for floating-rate risk, today’s borrower must also be willing to start out with a variable rate that isn’t much lower than its fixed-rate equivalent.

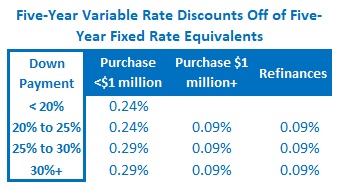

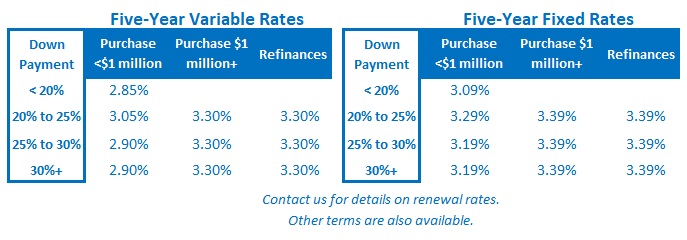

To illustrate this point, here is a table that summarizes the discounts available if you opt for a five-year variable rate today instead of its fixed-rate equivalent, based on different purchase prices, transaction types and down-payment amounts:

The spread between variable and fixed rates is now unusually narrow because the factors that have made the BoC more dovish have also pushed down Government of Canada (GoC) five-year bond yields, which our five-year fixed-rate mortgages are priced on. To wit, the five-year GoC bond yield was at 2.39% when the BoC completed its last rate rise on October 24, 2018, and it closed at 1.60% last Friday.

So there’s the rub for anyone making the fixed- versus variable-rate call today.

If you choose a variable rate, it isn’t likely to rise over the next twelve to eighteen months, and it may actually fall. But five years is a long time, and the farther out you go, the harder it is to predict what will happen to mortgage rates with any degree of accuracy because there are just too many factors that come in to play.

Here are five wild cards that could lead to unexpectedly higher rates:

- Our federal government might respond to sluggish economic conditions with ill-advised fiscal stimuli that exacerbate inflationary pressures (especially in an election year).

- Sector-specific labour shortages could fuel price increases even in a low-growth environment.

- Geopolitical tensions could cause a spike in energy prices.

- A sovereign debt crisis (i.e. in the EU) could lead investors to re-price bond-market risk premiums worldwide.

- A plunging Loonie could fuel a sharp increase in import prices.

The BoC has been very clear that its sole mandate is to keep inflation low and stable, and furthermore, that it will adhere to that mandate even if doing so triggers negative side effects across other parts of our economy.

If any of the five scenarios outlined above (and/or others not listed) were to come to fruition and the BoC were to raise its policy rate in response, today’s variable-rate borrowers wouldn’t have much buffer to work with. Conversely, borrowers who opt for a five-year fixed rate today need pay only a very small premium in exchange for the security of knowing that their payment won’t change for the next five years.

The Bottom Line: I think that five-year variable rates will likely prove cheaper than their fixed-rate equivalents over the next five years. That said, I think the saving won’t be as dramatic as it has been in years past, and if borrowers want to guard against wild-card scenarios like the ones I have outlined above, today’s five-year fixed-rate premiums are miniscule by any historical comparison.

The Bottom Line: I think that five-year variable rates will likely prove cheaper than their fixed-rate equivalents over the next five years. That said, I think the saving won’t be as dramatic as it has been in years past, and if borrowers want to guard against wild-card scenarios like the ones I have outlined above, today’s five-year fixed-rate premiums are miniscule by any historical comparison.

2 Comments

Thanks!!! Great article!!

Informative post.