Canadian Inflation Ticks Higher But Remains Subdued

October 26, 2020Will October Mark the End of Canada’s Employment Recovery?

November 9, 2020 Last Wednesday the Bank of Canada (BoC) announced that it would keep its policy rate at 0.25%, as was universally expected.

Last Wednesday the Bank of Canada (BoC) announced that it would keep its policy rate at 0.25%, as was universally expected.

In its latest policy statement, press-conference commentary, and Monetary Policy Report (MPR), the Bank offered unusually clear guidance on the future path of interest rates, which will be extraordinarily useful to anyone in the market for a mortgage.

In today’s post I’ll highlight the key points from the Bank’s communications and then explain why I think its latest guidance should put an end to the fixed vs. variable debate until face masks are a distant memory.

Key Point #1 – Uncertainty Reigns

The BoC emphasized that the pandemic’s path is still “highly uncertain.”

It based its current projections on the assumption that “vaccines and effective treatments will be widely available by mid-2022” but also acknowledged that “the effects from the uncertainty surrounding COVID-19 are … likely to linger.” The Bank’s examples of the negative impacts from that uncertainty included business failures, reduced investment spending and changes in consumer behaviour.

Key Point #2 – The Recovery Remains Uneven

Employment levels in the lower-income groups, especially those in “high-contact services,” remain the hardest hit, while employment levels in the higher-income groups have now risen above their pre-pandemic levels.

Overall, 720,000 Canadians are still out of work due to “pandemic-related job losses.” For comparison, job losses during the Great Recession peaked at 400,000. The difference is that back then, the losses were spread across all income groups, whereas now they are concentrated in the lowest income groups.

Key Point #3 – The Toughest Stretch Is Still Ahead

The BoC noted that both the global economy and the Canadian economy experienced an initial rebound that was “stronger than expected”, but it also reaffirmed that we are now in the midst of a “slower, more protracted recuperation phase.”

The Bank added that our hard-won momentum has recently experienced a “near-term slowing” that is tied to the recent rise in COVID-19 infections.

Key Point #4 – Rates Aren’t Going Up until at Least 2023

The BoC had previously said that it would maintain its current monetary-policy path until our economic recovery was “well underway.” Last week it went a step further and offered a more specific timeline, explaining that it was “providing exceptional forward guidance to provide as much clarity as we can to Canadians.”

The Bank now expects that it will take until the start of 2022 for our GDP to return to its pre-pandemic level, and forecasts that our output gap won’t close until 2023.

As a reminder, the output gap refers to the gap between our economy’s actual output and its maximum potential output. Inflationary pressures rise when the output gap closes, and the BoC has made it clear in past commentaries that it would begin raising its policy rate around that point.

In his accompanying press conference, BoC Governor Tiff Macklem reinforced the Bank’s guidance when he said that “Canadians can be confident that interest rates will be low for a long time.”

Key Point #5 – Negative Interest Rates Aren’t on the Table

The BoC has repeatedly referred to its current policy-rate level of 0.25% as its effective lower bound, otherwise known as its floor.

When asked if the Bank would consider dropping its policy rate into negative territory, Governor Macklem answered, “in the current situation it’s not something we think would be very helpful, and, in fact, could be disruptive.”

While he acknowledged that taking its policy rate negative was an option in the Bank’s toolkit, he quickly added that “the bar [for doing so] … would be very high.”

One caveat: All bets are off if the U.S. Federal Reserve takes its policy rate negative. If that happens, the BoC will have no choice but to follow the Fed’s lead to prevent the Loonie from soaring against the Greenback.

Key Point #6 – The BoC Is Recalibrating Its Quantitative Easing (QE) Program

In April, the Bank committed to purchasing a staggering $5 billion/wk worth of government bonds, and last Wednesday it announced that it would gradually reduce that commitment to $4 billion/wk.

Despite this reduction, Governor Macklem confidently predicted that an accompanying shift in the Bank’s focus will ensure that its revised QE program will provide ”at least as much stimulus” as before.

Until now the BoC has purchased mostly shorter-term bond maturities (of two years or less), but going forward, it plans to buy bonds with longer-term maturities that are tied to “borrowing rates that are most relevant for households and businesses.”

If the BoC is going to focus on bonds that are tied to the borrowing rates most relevant to households, then its primary target will have to be the five-year Government of Canada (GoC) bond, which our five-year fixed-rate mortgages are priced on.

Now revisit the age old fixed vs. variable question:

Should You Choose Fixed or Variable?

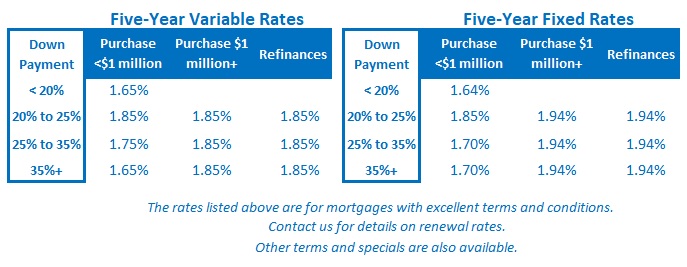

Variable rates are at almost the same level as fixed rates at the moment (see chart below), and normally, when the gap is that narrow, borrowers opt for fixed because they aren’t getting rewarded for taking on the risk that variable rates might rise.

But how much variable-rate risk is there now that the BoC is saying that it doesn’t expect to raise its policy rate until some time in 2023? Canadians have never heard that kind of explicit forward guidance from their central bank.

On top of that, the BoC just telegraphed that it will be buying five-year GoC bonds by the truck load for years to come (to drive down the borrowing rates that most affect households).

Bluntly put, five-year fixed mortgage rates have only one direction to go in the next two or three years: down. And the only questions left are how low they will go, and how long it will take.

Do you really want to lock in a five-year fixed-rate contract now when we’ve just learned that the BoC is about to turn its monetary-policy guns on the GoC bonds your rate is priced on? Especially since, in many cases, fixed-rate mortgages come with prepayment penalties that are so onerous you’ll be stuck watching rates fall while you wait out the end of your term?

Conversely, if you take a five-year variable rate today, you will start out with a slightly lower rate that the BoC has just said won’t rise until at least some time in 2023. More importantly, if fixed rates fall in the interim, as expected, you will have the option to convert at any time, and at no cost. (Note: Variable rates can be converted to fixed rates, but fixed rates can’t be converted to variable rates.)

Some borrowers worry that their lender might not offer a fair conversion rate if they do want to convert from variable to fixed. That would be risky for the lender because variable-rate mortgages can be broken with a small penalty of only three-months’ interest. If the conversion rate they offer isn’t competitive, paying that penalty will get you out of your contract and open up access to the most competitive fixed mortgage rates available in the market at that time.

In summary, today’s variable rates give you much more flexibility to take advantage of falling rates in the years ahead while the BoC’s explicit forward guidance greatly reduces your interest-rate risk.

One-sided bets don’t come along very often, but this sure looks like one to me. The Bottom Line: Last week the BoC confirmed that variable mortgage rates won’t rise until at least 2023 and aren’t likely to fall unless Mars hits Earth.

The Bottom Line: Last week the BoC confirmed that variable mortgage rates won’t rise until at least 2023 and aren’t likely to fall unless Mars hits Earth.

The Bank also confirmed that it would shift its QE program’s focus toward bonds that are tied to “borrowing rates that are most relevant for households and businesses.” That puts a bullseye on the five-year GoC bond, which our five-year fixed mortgage rates are priced on, and makes it a virtual certainly that they will move lower as a result.

2 Comments

Very insightful, thanks.

Thanks David. Glad you found it useful.