Dave Is Currently Dockside

July 27, 2020A Theory on Why CMHC President Evan Siddall Went Rogue Last Week

August 17, 2020Canadian mortgage rates have been on a wild ride of late.

It started in late February when five-year fixed rates were available at about 2.75% and five-year variable rates were offered in the 2.90% range. Most borrowers were opting for the stability of a fixed rate against that backdrop, which had been in place for some time.

Then the crisis hit, and the Bank of Canada (BoC) slashed its policy rate by 0.50% three times in March, dropping it from 1.75% all the way down to 0.25%.

Variable mortgage rates initially fell in response, but then as the severity of the crisis became more evident, they started moving up instead of down. Here is a brief explanation of how and why that happened:

- Variable mortgage rates are priced on lender prime rates, which typically move in lockstep with the BoC’s policy rate.

- When the BoC’s policy rate plummeted, lenders followed suit and dropped their prime rates, but they also shrunk the discounts off prime that they were offering to variable-rate borrowers.

- To wit, lender prime rates dropped from 3.95% in late February to 2.45% by mid-April, but over that same period five-year variable rates only climbed from prime minus 1.00% (2.95%) in late February to prime (2.45%) by mid-April.

- In other words, the BoC’s policy rate dropped by 1.50%, but five-year variable mortgage rates only fell by about 0.50%.

- The elimination of the variable-rate discount was caused by COVID-related risk premiums that had been added by both financial markets and lenders.

Over that same period, five-year fixed rates actually moved higher, from about 2.75% up to about 3%, despite the fact that the Government of Canada (GoC) five-year bond yield they are priced on dropped from 1.35% to 0.44%. The sharp drop in the GoC bond yield was more than offset by new COVID-related risk premiums.

In April, I wrote that variable-rate mortgages had suddenly become the slam-dunk option for all but the most risk averse borrowers. I speculated that our policy maker’s unprecedented fiscal and monetary policy actions would cause the COVID-related risk premiums that were pushing up rates to dissipate over time, and that the flexibility inherent in variable-rate mortgages would allow borrowers to take advantage when that happened.

(Reminder: variable-rate mortgages can be converted to fixed rates at any time, and the penalty to break them is only three months’ interest.)

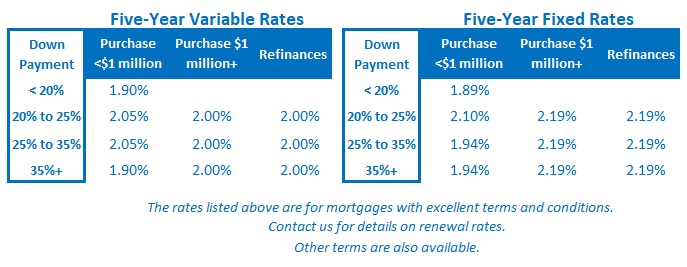

Today, four months later, five-year fixed and variable rates are offered in the high 1%/low 2% range.

Anyone who followed my advice in April will be glad they did because they can already save money by either converting their original five-variable rate of 2.45% down to a five-year fixed rate below that level or by paying a penalty of three months’ interest and refinancing down to a lower variable rate instead.

Other borrowers are not so lucky.

For example, anyone who took a fixed-rate mortgage with a major bank in April will be looking at a huge penalty to break their mortgage (which I warn about in this blog all the time). Those borrowers are likely to be stuck with their original rate until the end of their term.

Now that rates have moved lower, let’s take a fresh look at the fixed vs. variable question, and to do that, let’s start with a summary of the current situation:

- Mortgage rates have fallen to record lows.

- The BoC is now engaged in aggressive quantitative easing (aka money printing).

- Government debt is exploding.

That backdrop has led some to speculate that higher inflation is coming and that fixed-rate mortgages are the better bet. CIBC economist Benjamin Tal recently warned that “it is very likely that the Bank of Canada will raise rates at least once in the coming 3.5 years.”

That’s certainly what should happen based on what we were taught in economics class. (Full disclosure: my Eco 101 classes started at 7:45am and I was not a regular attendee).

But recent history isn’t lining up with what those old textbooks say should happen.

For example, Japan has been printing money and borrowing up to its eyeballs since 1991, and its inflation rate has spent more time below 0% than above it since then. Over the past decade the eurozone has printed and borrowed staggering amounts, but that hasn’t yet fuelled a spike in inflation there either.

Governments and central banks can inject money into their financial systems as much as they want. If lenders don’t lend and borrowers don’t spend, it won’t fuel inflation.

BoC Governor Tiff Macklem doesn’t sound remotely worried about inflation going forward. He recently took the unusual step of reassuring Canadians that “interest rates are going to be low for a long time.”

In this recent post and also this one, I explained why I think rates aren’t likely to rise for an extended period and why they will drop further before they do rise. Here is a summary of the key points:

- The recovery is going to take longer than the consensus believes. Consider that the BoC is calling the current crisis “the steepest and deepest economic decline since the Great Depression.”

- The BoC already believes that rates are going to stay low, and that view includes the assumption that we won’t get hit with a second wave, even though every other pandemic in history has had one. If the Bank ends up being wrong on that point, rate hikes would be delayed even more. (I hope they’re right, but I fear they won’t be.)

- Inflation fears are being fuelled in part by recent encouraging economic data. But I agree with the BoC that the current dramatic re-opening phase will be followed by what it calls “a slower and bumpier recuperation phase,” where momentum will be much harder to come by.

- The U.S. government’s poor response to COVID has exacerbated the negative economic impacts of the virus. If the U.S. economic slump drags on, so will ours.

- The BoC’s primary concerns surround the “strongly disinflationary” impacts of this crisis. Given that, even if above target inflation does materialize for a period of time, the Bank is likely to tolerate it for longer than it normally would.

- Excessive debt – and the payments it requires – are crowding out our economy’s ability to access the resources it needs for healthy growth. There is now a growing consensus that high debt levels reduce inflation rather than stimulate it. (See Japan and the eurozone for two recent examples.)

- Technological innovations are reducing the cost of almost everything. This is a long-term trend that won’t be going away anytime soon.

I understand why borrowers are tempted to lock in today’s record-low fixed rates – and to be clear, I would never try to talk anyone out of that choice because nobody can know for certain what will happen, and each borrower has to bear the cost of their decision. Also, anyone who is going to lose a lot of sleep worrying that their mortgage rate could rise should still opt for the comfort of a fixed rate (as long as they stay away from those onerous Big Bank penalties).

But my fixed vs. variable blog posts offer my unvarnished opinion on which option will likely prove less costly over the next five years. I continue to lean towards variable for the following reasons:

- I think fixed rates will continue to fall. If I’m right, variable-rate borrowers will have the option to convert to lower fixed rates (at no additional cost) over the next five years.

- I think variable-rate discounts will continue to widen. If I’m right, existing variable-rate borrowers will be able to break their current contracts with a penalty of only three-months’ interest. Variable-rate discounts don’t have to widen by much to cover that cost.

- I think the risk that variable rates will rise over the next several years is lower than it has been in my 20 years in this business. Given that, in my view it would be a wise choice to accept the risk that rates might rise sooner than expected in exchange for greatly enhanced flexibility to access lower rates.

The Bottom Line: Five-year variable rates fell a little last week, and five-year fixed rates were unchanged. For the reasons outlined above, I think rates are likely to continue to move lower over the short and medium term, and with that in mind, I think that a five-year variable mortgage rate will prove the better option.