Canadian Fixed Mortgage Rates Are About to Rise

February 22, 2021Fixed or Variable Mortgage Rate – Which One Should You Choose?

March 8, 2021The inflation trade pretty much exploded last week.

Investors bet that we’re going to get more inflation than our policy makers expect, and they drove up bond yields in response.

The Government of Canada (GoC) five-year bond yield that our five-year fixed mortgage rates are priced on surged from 0.67% at the start of the week to 0.88% at Friday’s close (and it was at only 0.43% when February began). Lenders responded by raising their five-year fixed rates anywhere from 0.15% to 0.25% (so far).

This bond yield surge is a global phenomenon that is primarily underpinned by the belief that US inflation is about to sustainably rise (which I also wrote about in last week’s post). If that happens, the US will export its rising inflation through trade, and it will permeate the globe.

There are good reasons to fear higher US inflation. The Biden administration has proposed a huge COVID relief package that just passed in the House of Representatives. If it clears the Senate and is enacted, the US federal government will have provided a total of $7 of stimulus for every $1 lost to the pandemic.

New Treasury Secretary and former US Fed Chair Janet Yellen is emphasizing the need to “act big” with stimulus, and the US budget deficit and US government debt have already skyrocketed (as is the case in many other countries, including Canada).

Investors fear that unchecked spending will lead to runaway inflation. This fear is exacerbated by the increasing popularity of an idea called Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), which was widely dismissed before the pandemic but is now gaining mainstream adherents. It theorizes that governments in mature, developed economies can simply print the money to pay for massive amounts of spending, without needing to borrow in the bond market or recovering the spent funds through increased taxation.

Policy makers aren’t seriously considering MMT, at least for now, but bond-market investors aren’t waiting around to find out what they might turn to next.

Against that backdrop, US vaccination rates are soaring (42 million and counting), infection rates are falling, and the consensus expects that US consumers are about to unleash the huge piles of cash that have built up on their personal balance sheets. If that happens, US inflation, which has already risen from 0.1% to 1.4% over the past nine months, will accelerate further.

In the meantime, while we’re waiting to see if that unfolds, the US Consumer Price Index (CPI) is virtually guaranteed to rise because it uses prices over the most recent twelve months, and prices that plummeted last April and May are about to roll out of the calculation. (This one-time effect will cause the CPI to rise, but only temporarily as prices return to their more normal levels.)

Sentiment about inflation matters because if consumers and businesses are worried about price rises, they may accelerate their purchasing and trigger a spike in demand that causes more inflation. Thus, in a self-reinforcing feedback loop, fear of higher inflation can actually end up being its primary cause.

Surprising as this may sound after what I have just written, I still don’t believe that we’re headed for anything more than a transitory inflation spike – and as such, I don’t think the current bond-yield run up will last.

Here are five reasons why:

- Commodity prices are rising, but not for reasons that portend sustainably higher inflation.

Commodities are the raw materials used in production, so when their prices rise, they raise the cost of everything that is made from them.

But commodity prices rise for different reasons.

If commodity prices are rising because of increased demand, it is reasonable to assume that higher prices will be sustained for as long as demand stays strong. But today’s commodity prices are rising primarily because the pandemic has created supply shortages and transportation challenges. Once these challenges are overcome, commodity-price pressure should ease.

On a related note, and this hasn’t had much mention recently, China has been the marginal buyer of commodities for more than a decade, and that means Chinese demand has largely determined whether commodity prices rise or fall. Unlike almost every other large economy, China is now reducing stimulus and appears willing to endure some short-term economic hardship in order to preserve its longer-term economic health.

If Chinese demand cools, that will have a much more significant and enduring impact on commodity prices than the current supply challenges.

- More debt hasn’t led to more inflation thus far.

If you crack open an economics textbook, it won’t take long before you read about how rising debt fuels rising inflation.

But reality hasn’t borne that out.

Japan has been printing money at eye-watering levels for 30 years, and yet its policy makers have spent most of their time trying to create inflation, not dampen it.

Instead of causing inflation, higher debt levels in Japan have killed it. And not just in Japan. The same pattern is seen in all of the mature, developed economies that significantly increased their debt levels in response to the 2008 financial crisis.

Rising debt levels have slowed the rate at which money circulates throughout economies (referred to as the velocity of money), and rising debt-service costs will increase the share that debt demands from the overall spending pie.

Simply put, debt has proven to be deflationary.

- The US economy has plenty of spare capacity.

The US output gap, which measures the gap between its economy’s actual output and its maximum potential, remains wide (and the same is true in Canada).

Inflationary pressures aren’t expected to rise sustainably until that gap comes close to closing – and today the US output gap is the widest it has been since the depths of the Great Recession in 2009.

To cite a more specific example, labour is by far the highest input cost for most businesses and the world’s developed economies have experienced record levels of unemployment during the pandemic. While not all of the unemployed workers have the skills needed to fill all of the positions that our economy will demand going forward, it is hard to imagine labour costs rising significantly for as long as there are so many sidelined workers.

Put another way, if the US economy couldn’t average 2% inflation when its unemployment rate was 3.5%, why would we expect inflation to rise sustainably above 2% when unemployment is now at 6.3%?

- Technological developments and productivity enhancements are accelerating.

Technological advances and productivity enhancements were already reducing costs before the pandemic. (In a post last year, I noted that Amazon already employed more robots than people.)

When COVID hit, businesses were forced to innovate on the fly, for example, by having staff work from home and by using teleconferencing to replace in-person meetings. Many of these changes proved successful, and if they are made permanent, they will reduce the future need for office space, business travel and many other expenses.

These advances and other cost-efficient changes will continue to exert a long-term disinflationary impact on prices.

- The pandemic has changed the way we live.

The difference between a recession and a depression is that after a recession, things pretty much return to normal, whereas a depression causes permanent behavioural changes in the way we live.

I still don’t buy the mainstream vision of a repeat of the Roaring Twenties awaiting us. Yes, we’ll all go out for a dinner on the town when the pandemic ends, and probably a trip to somewhere other than our family-room couch, but what about after that?

My bet is that we’ll revert back to our newly formed habits of eating at home more, walking instead of driving, and repairing instead of replacing. In other words, spending less than we did before COVID.

If I’m right, any surge in demand that pushes prices higher will be short lived.

For their part, our policy makers don’t sound worried about meaningfully higher inflation either. Last week, BoC Governor Tiff Macklem delivered a speech, and in the Q & A that followed, he interpreted the rising bond yields as a sign that our economy is returning to health but reiterated the Bank’s belief that our economy’s road to recovery will be a long one.

Here are my two cents for anyone in the market for a mortgage today.

Variable mortgage rates were already appealing before the recent rise in fixed rates, and now I think they are even more so.

The BoC continues to reiterate its pledge not to increase its policy rate, which variable mortgage rates are priced on, until sometime in 2023. That gives anyone starting a new term today two years of runway before rate increases are even a possibility. If I’m right, and this fixed-rate run-up proves to be short lived, variable-rate borrowers will also have a future option to convert to fixed rates at least as low as the ones we will have left behind once the dust settles.

Of course, that is not a guarantee. I have been polishing my crystal ball for many years now, but it is still murky. That said, both my research and my gut point to a future that will be different from the current consensus prediction.

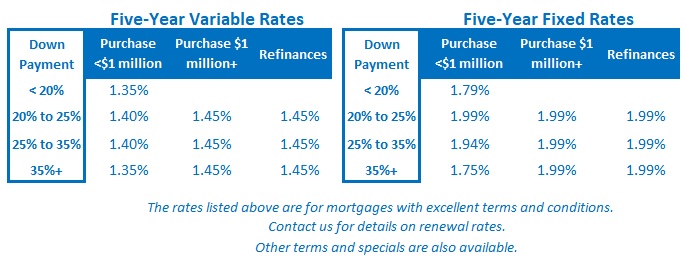

The Bottom Line: Five-year fixed rates moved sharply higher last week as lenders raised between 0.15% and 0.25% (depending on down-payment amounts and insurability).

The Bottom Line: Five-year fixed rates moved sharply higher last week as lenders raised between 0.15% and 0.25% (depending on down-payment amounts and insurability).

Variable rates actually moved lower, with a few lenders increasing their variable-rate discounts off prime. That has widened the gap between fixed and variable rates to a level we haven’t seen in some time. (And we may not be done yet.)