How the 2022 Federal Budget Will Impact Our Real-Estate Markets

April 11, 2022Fixed vs Variable: Which One Is Now the Better Bet?

April 25, 2022 Last Wednesday the Bank of Canada (BoC) raised its policy rate by 0.50%, marking its first half-point hike since May 2000. The Bank also stated that inflation is going to be “elevated for longer than we previously thought” and advised Canadians to “expect further increases”.

Last Wednesday the Bank of Canada (BoC) raised its policy rate by 0.50%, marking its first half-point hike since May 2000. The Bank also stated that inflation is going to be “elevated for longer than we previously thought” and advised Canadians to “expect further increases”.

In addition to its policy statement, the BoC issued its latest Monetary Policy Report (MPR), and Governor Tiff Macklem and Senior Deputy Carolyn Rogers spoke at the accompanying press conference.

After reviewing all the Bank’s latest communications, here are the five key points that I think are most important for Canadian mortgage borrowers and for anyone concerned about where our fixed and variable rates may be headed.

- The BoC offered a full mea culpa for its previous inflation forecasts.

Central bankers around the world rue the day they decided to use the word “transitory” to describe inflationary pressures tied to the pandemic. While the official definition of that word means “not permanent”, the pandemic-related use of that term by central bankers evolved to mean “short lived”, and that cost them a hit to their credibility.

BoC Governor Macklem didn’t try to duck that missed call.

He offered a complete mea culpa for the Bank’s recent inflation forecasts, conceding that “inflation is too high. It is higher than we expected, and it’s going to be elevated for longer than we previously thought.”

The Bank’s latest MPR forecasts that inflation will average almost 6% in the first half of 2022 (a thirty-year high) and will remain well above its target of 2% for the rest of this year, before dropping down to 2.5% in the second half of 2023 and finally returning to target in 2024.

My sense this time around is that the Bank is trying both to ensure that its latest inflation forecasts err on the high side in its efforts to restore credibility and to wrest back control over the inflation narrative.

(Side note: Macklem did not offer any similar mea culpa for the BoC’s oft repeated pandemic guidance that rates would “stay low for a long time” or that the BoC wouldn’t start hiking rates until “some time in 2023”.)

- The BoC tried, but failed, to make a bullish case for hikes.

The Bank is in a tough spot.

It needs to raise its policy rate aggressively to keep inflation expectations anchored and to reassure Canadians that it will do whatever is necessary to bring inflation back to its 2% target, but it also wants to project confidence that our economy “can handle higher interest rates”.

For several reasons, I am concerned about whether that will prove to be the case.

For starters, while the BoC noted “strong growth” in consumer spending thus far in 2022, some of that momentum carried over from earlier emergency stimulus payments, which ended late last year. That fiscal tailwind for consumer spending will abate going forward.

Unlike at the height of the pandemic, the sharpest price rises that we are seeing today are in commodities (especially energy and food) that consumers can’t do without, and that will reduce their spending capacity in other areas.

The Bank noted that job growth has been “strong” and predicted that positive employment momentum will also boost spending. But while our headline job growth has been impressive over the past year, it has also corresponded with a steady decline in productivity, and that explains why wage growth is only now recovering to its pre-pandemic level.

The threat that rising labour costs could cause inflation to get out of control is real, but thus far those costs haven’t broken out. Aggressive rate hikes will significantly reduce the odds that they will, and while that would be good news for inflation, less concomitant demand for labour would be bad news for consumer-spending growth.

In a long-standing but curious MPR tradition, the BoC reiterated its prediction that “robust business investment” will take the reins from housing activity and become the primary driver of our economy going forward. While I have no doubt that rate hikes will slow housing activity, I have watched the hair on my head turn gray waiting for business investment to take the lead.

The Bank may be hoping that higher oil prices will increase business investment in the oil sands. But our oil companies have been decidedly, and understandably, more cautious about ramping up investment after the last oil-price crash and still more so given the constant delays and uncertainties surrounding construction of the Trans Mountain Pipeline and our federal government’s messaging regarding the oil patch.

The BoC’s rate hikes aren’t going to address the supply constraints that are causing most of today’s elevated inflation pressures. Instead, they will push demand down to meet supply at its currently impaired levels. Against that backdrop, I think the Bank’s forecasts for GDP growth of 4.5% in 2022, 3.25% in 2023 are overly optimistic.

- How high will the BoC’s policy rate go?

The BoC now estimates its neutral rate to be in the 2% to 3% range, an increase of 0.25% over its April 2021 estimate.

The Bank’s neutral rate is defined as the policy rate that will allow the economy to operate at its full potential while keeping inflation constant at or near the Bank’s 2% target.

The BoC’s policy rate now stands at 1%, well below its estimated neutral rate of 2% to 3%. That means we could potentially have another 1% to 2% worth of rate hikes in store – and more if the Bank wishes to go beyond neutral to lean hard against today’s inflation.

The neutral rate is by its nature a moving target, and the Bank may decide to let its policy rate run above or below the neutral level, even for an extended period, if it feels the need to impact inflation one way or another. For example, in its most recent communications, the BoC acknowledged that it may pause its rate hikes to “take stock” before reaching its neutral-rate range and “will be assessing the impacts of higher interest rates on the economy carefully.”

That makes perfect sense when you consider that the impacts from rate hikes occur with a lag and can take a full 12 to 24 months to exert their full effects.

For my part, I continue to believe that today’s record-high debt levels will magnify the impact of each rate hike, making it unlikely that the Bank will have to raise by as much as many observers predict. The Bank will also have to be careful not to raise its policy rate too high because this would trigger an economic slowdown that would compel it to reverse course.

- Our economically crucial housing markets are now being tested.

The BoC’s damn-the-torpedoes approach to reducing inflationary pressures will severely test our housing markets.

Five-year fixed rates have just experienced their most dramatic run-up in more than twenty years, and the most recent increase is, for the first time, taking the rate used to qualify fixed-rate borrowers along with it. This rising fixed-rate trend shows no sign of abating over the short term, especially when you consider that the BoC starts its quantitative tightening (QT) program later this month (more on that below).

At the same time, variable rates have risen by 0.75% over the past six weeks, and the BoC is warning that there are more rate hikes to come.

Most mortgage borrowers had to be qualified at much higher rates than the ones they are currently paying, but they will feel the pinch of higher borrowing costs nonetheless, and that will crimp their spending in other areas.

Meanwhile, potential home buyers who have watched house prices soar are now wondering whether our real-estate markets can continue to withstand today’s price levels in the face of higher mortgage rates. Some buyers have become more cautious, and more will likely follow as rates continue to rise.

That change in sentiment could feed on itself, especially in real-estate markets that have not experienced any sort of price drop for some time. Any material slowdown in real-estate activity will create a large hole in our economic momentum, which other economic drivers will have their work cut out to fill.

- The BoC will start quantitative tightening on April 25.

When the pandemic hit and the BoC slashed its policy rate to 0.25%, it also announced that it would use quantitative easing (QE) to purchase huge quantities of Government of Canada (GoC) bonds.

QE was initially designed to ensure that our financial markets remained liquid, but once that objective was achieved, the BoC shifted the focus of its program to drive down GoC bond yields and the interest rates that are priced on them, such as our fixed mortgage rates.

This continued until last November when the Bank announced that it would end its QE purchases and shift to a neutral stance, which it called the “reinvestment phase”, buying only those bonds that were issued to replace others that they had already owned.

Last week the Bank confirmed that it would stop reinvesting in its renewing bonds on April 25. This new phase, referred to as quantitative tightening (QT), means that within a relatively short period of time, the Bank will go from being the largest purchaser of GoC bonds to the largest seller.

Put another way, QE lowered GoC bond yields and the fixed mortgage rates that are priced on them at the height of the pandemic. QT will now produce the opposite effect going forward.

Now let’s close with some specific advice for borrowers who are currently in the market for a mortgage.

Fixed-Rate Advice

We have already seen a dramatic spike in fixed-rate mortgages over a short period and once they finally peak, if past is prologue, it is more likely that those rates will decline on the other side rather than plateau thereafter.

We have already seen a dramatic spike in fixed-rate mortgages over a short period and once they finally peak, if past is prologue, it is more likely that those rates will decline on the other side rather than plateau thereafter.

Borrowers who prefer the certainty of locking in a fixed rate today are well advised to ensure that their mortgage contracts include fair prepayment penalties (which are by no means universal and you can learn more about why I write that here). This will ensure that if fixed rates do soften in the future, borrowers will have the option to break their mortgage at reasonable cost and (potentially) achieve some saving.

Variable-Rate Advice

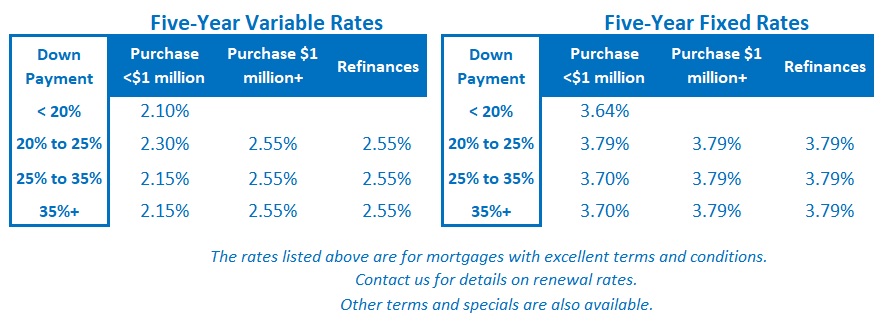

Variable rates are still available at discounts of more than 1% over their fixed-rate equivalents, and I continue to believe that they have the potential to save borrowers money over the next five years.

That said, variable-rate borrowers are well advised to get used to higher borrowing costs and increased payments. This can be done by voluntarily increasing their payment above its current level by making it equivalent to today’s fixed-rate mortgage payments.

This make-hay-while-the-sun-shines approach will ensure that today’s variable-rate saving is used to reduce principal and will also create a cash-flow buffer that can be toggled back to absorb the next several BoC rate increases without impacting monthly cash flow. The Bottom Line: Five-year fixed rates held steady last week, but all their momentum still points up.

The Bottom Line: Five-year fixed rates held steady last week, but all their momentum still points up.

Meanwhile, the BoC’s 0.50% policy-rate rise has caused variable rates to surge higher by the same amount, and the Bank made it clear that there are more hikes to come.

While the variable-rate ride is getting bumpy and will probably remain so over the short term, I still think we’re likely to see fewer rate hikes than the consensus predicts. That said, if the BoC does track the consensus forecast, I think it will tip our economy into recession and that rate cuts will follow thereafter.

1 Comment

Thanks for your insights, Dave! After hearing your episode on the ILMB podcast I’ve been following your blog regularly. Your perspective is always refreshingly sensible compared to some of the rate drama out there. 🙂