How the Coming Mortgage Rule Changes Are Likely to Impact Canadians in 2018

December 18, 2017Canadian Mortgage Rate Forecast for 2018 – Part 2 (Five-Year Variable Rates)

January 15, 2018First off, I’d like to wish a very happy new year to my readers.

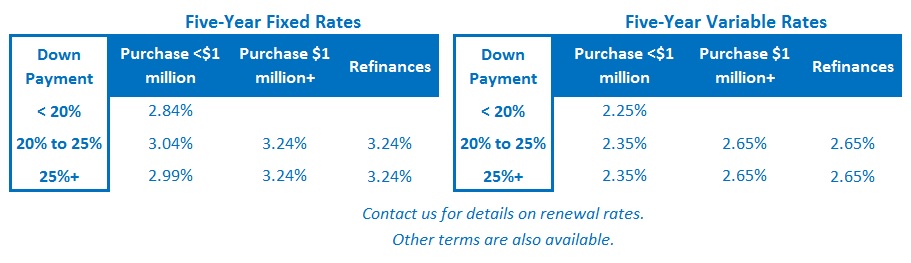

In today’s post I offer my forecast for five-year fixed rates in 2018, and next week, I’ll do the same for five-year variable rates.

Five-year fixed mortgage rates bottomed in the low 2% range in the first half of 2017 and by the end of the year they had climbed back up to around 3%. This marked the most significant proportional increase that we have seen in fixed rates since the start of the Great Recession.

In spite of that, a five-year fixed rate of 3% is still dirt cheap by any historical comparison and today the vast majority of Canadians can afford their mortgage payments. This reality is borne out by today’s overall mortgage default rate, which stands at its lowest level in decades.

But if rates continue to rise, affordability will deteriorate.

Our elevated household debt levels are keeping our policy makers up at night and are the reason why they have enacted six rounds of mortgage rule changes since rates first plunged in 2008. (Bluntly put, any credible market observer must acknowledge that the changes were both necessary and prudent.) With our overall household debt levels at record highs after a decade of rock-bottom rates, an increasing number of highly leveraged borrowers will have difficulty keeping up their payments. (This reminds me of Warren Buffet’s famous quote: “Only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked.”)

The key question for mortgage borrowers and, more broadly, for real-estate markets across the country (since the majority of Canadians opt for five-year fixed-rate mortgages) is whether rates will rise this year, and if so, by how much.

In normal times the most significant risk to our fixed mortgage rates is inflation, where even a small uptick, if viewed as long-term or the beginning of an uptrend, will send Government of Canada (GoC) bond yields higher. And since our fixed mortgage rates are priced off of these yields, they will rise quickly in response.

Today, our overall inflation rate, as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), stands at 2.1%, which is a little above the Bank of Canada (BoC) target rate of 2%. The Bank’s more detailed inflation gauges have also crept up of late and aren’t too far away from their 2% targets. Furthermore, these trends jibe with the BoC’s belief that our economy is now operating very near to its full capacity.

Of note within the inflation data, our jobs growth has been strong over the past year and our average wage growth rate has risen sharply, from a low of 0.5% in April all the way to 2.9% in December (which is due, in part, to minimum-wage hikes in Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia). Wage rate growth is important because labour costs impact most prices across the broader economy.

Canada also imports a significant amount of inflation from the U.S. and rising inflationary pressures are evident there as well. U.S. inflation has picked up steadily over most of the past seven months and average U.S. wage growth, which hasn’t gone up much at all for the past several years, has recently risen to 2.5%.

All that said, in the present context, even with these current trends accounted for, higher inflation may not be the biggest risk to fixed mortgage rates in 2018.

The world’s largest central banks have been pumping liquidity into financial markets since the start of the Great Recession as a way to stimulate financial markets by suppressing longer-term bond yields (after having already dropped their short-term policy rates to the floor).

To give you an idea of the magnitude of its bond purchases, consider that the U.S. Federal Reserve has increased the size of its balance sheet by more than 500% since 2008, and it now holds bonds valued at about $4.5 trillion.

The Fed has announced that this year it will stop rolling over its maturing bonds (while also planning to continue hiking its short-term policy rate). At the same time, the European Central Bank (ECB) plans to reduce its bond purchasing program by 50%.

This will be a massive (and unprecedented) withdrawal of liquidity from financial markets and there is much debate about the impact it will have because the widespread use of unconventional monetary policy since 2008 has taken us deep into unchartered waters.

One thing we do know is that when the central banks of the world’s two largest economies reduce their influence on free market forces, the potential for destabilization will increase.

By now you can understand why many forecasters have been warning everyone to fasten their seatbelts and prepare for significantly higher mortgage rates on the horizon. But the contrarian in me thinks that now is a good time to remember one of Bob Farrell’s famous ten rules of investing: “When all the experts and forecasts agree, something else is going to happen”.

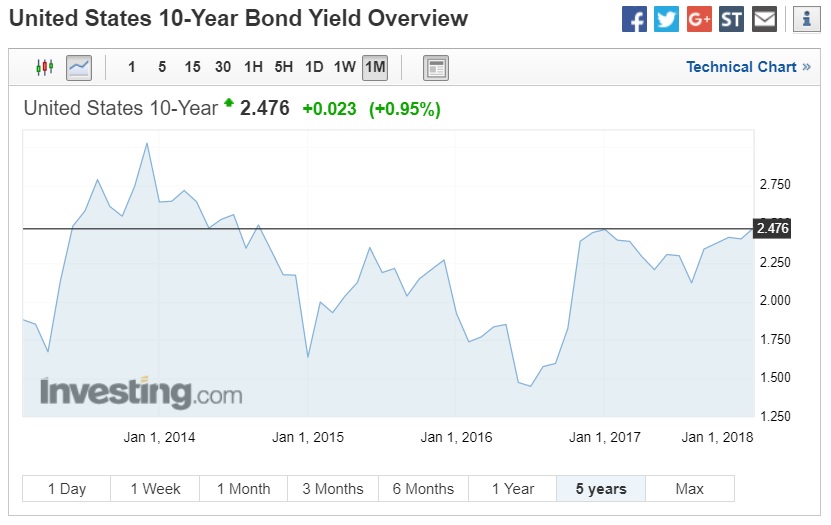

The first sign that the future might not unfold as the consensus expects can be found in longer-term bond yields, which have a long history of accurately forecasting future inflation. Low unemployment and accelerating wage growth haven’t yet convinced investors in ten-year U.S. and GoC bonds that they will need significantly higher yields to maintain their expected returns. (The charts below show the most recent five-year histories for both.)

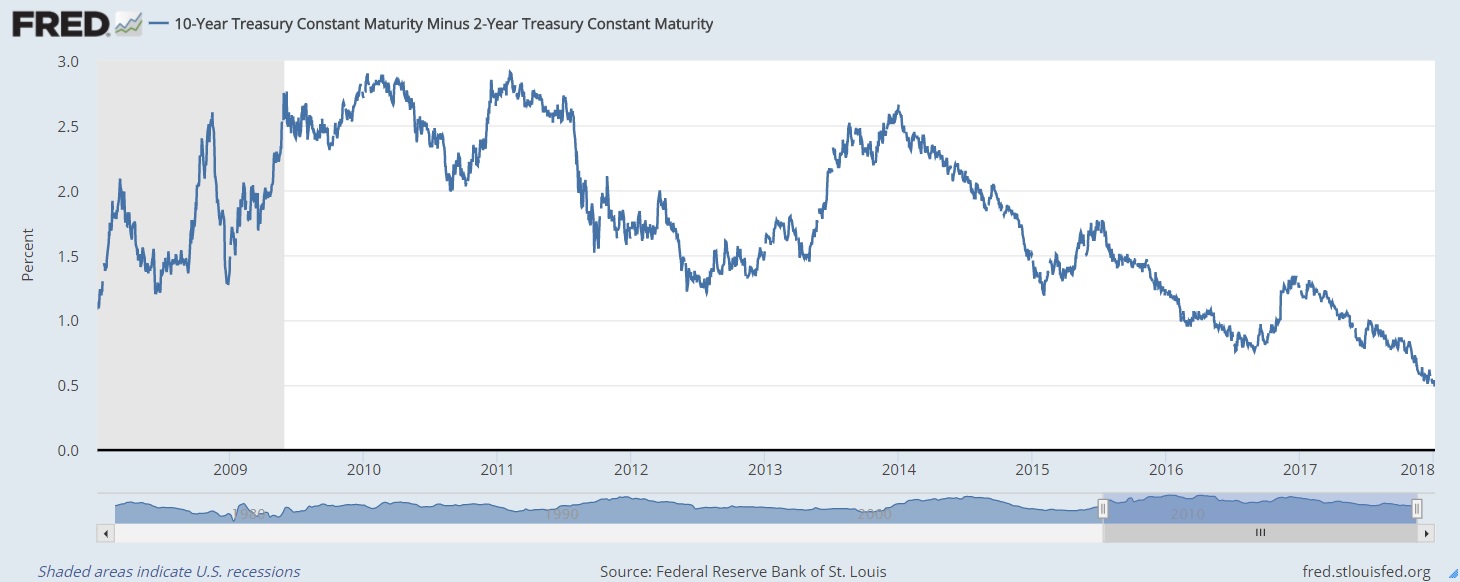

Another indication that bond investors aren’t overly concerned about significantly higher inflation can be found in the spread between U.S. two-year and ten-year bond yields. If investors are worried about higher inflation, this spread should widen, because rising inflation will have a greater impact on longer term bond yields. Interestingly, today the spread between two-year and ten-year U.S. bond yields is the lowest it has been in almost ten years, at 0.50%, and that’s about half of its long-term average of 0.97%.

I think the bond market’s muted reaction to the recent U.S. and Canadian inflation data is based on three primary factors:

- Demographics – Economist David Foote once famously said that “demographics explain about two thirds of everything”. In that context, consider that in the U.S. an average of 10,000 baby boomers now turns 65 each day (and there are 80 million of them in total). U.S. consumers account for more than two thirds of U.S. economic activity and if a significant (and unprecedented) number of those consumers are now hitting retirement age, that will have a profound impact on the U.S. economic cycle. Retirees spend less, and as more boomers retire, this group will exert downward pressure on inflation. They also save more (and invest conservatively), and that will ensure steady and growing demand for safe-haven assets like government bonds. We can see further evidence of the impact that aging demographics will have by looking at the speed at which money circulates through the U.S. economy, which is referred to as the velocity of money. M1 and M2 are the two most commonly used measures of money velocity and both now hover near all-time record lows.

- Debt – Debt is like an invasive garden weed that crowds out an economy’s access to the resources it needs for healthy growth. When resources are choked off, both supply and demand are limited and inflationary pressures are less likely to take hold on a sustained basis. Furthermore, if a rise in inflation is met with short-term policy-rate hikes, high debt levels magnify the effect of the rate increases. Rates don’t have to rise by much to slow growth and to relieve inflationary pressures.

- Technological Advances – We have entered a period where technological advances are dramatically reducing costs (as well as threatening many jobs). Companies like Uber and Amazon are turning industries on their heads, and there are many other less prominent examples. Consider that today Amazon has more robots than people working for it.

While these three factors are the main drivers that will help to keep inflation low over the long term, there are other short-term factors that will impact inflation as well. For example, in both Canada and the U.S., recent economic growth has been supported by rising debt levels and reduced savings rates. Neither source of stimulus is sustainable and when they both dissipate, as they must, growth will slow and short-term inflationary pressures will ease.

Our policy makers have expressed hope that business investment will make up for some of the expected slack in consumer expenditures, but in relative terms, business investment accounts for only a fraction of what consumer spending contributes to our overall GDP. Furthermore, it is hard to see business confidence rising as consumers start to pull back, especially at a time when there is also significant uncertainty around trade and heightened concern about geopolitical risks.

All that said, if we see tightening by central banks in the first half of 2018, that may well push mortgage rates higher for a time. But the powerful countervailing forces of demographics, debt levels, and technological change will not go away. Over the next five years, my admittedly minority view is that these forces will combine to overcome most, if not all, of the effects of near-term central bank policy-rate rises.

The Bottom Line: As I finish off this post, my inbox is filling up with emails from lenders announcing increases to their five-year fixed mortgage rates after the five-year GoC bond yield spiked in response to last Friday’s impressive employment report. In spite of this, the contrarian in me believes that forecasts calling for significantly higher five-year fixed rates have not adequately accounted for powerful long-term forces that will continue to exert downward pressure on them in the years to come.