Will the U.S. Fed Sooth Nerves or Stay the Course?

December 17, 2018The Glaring Omission in the Bank of Canada’s Latest Forecast

January 14, 2019At the start of 2018, forecasters focussed on the theme of synchronized global growth as signs of accelerating economic momentum abounded.

But that momentum did not prove self-reinforcing, as was hoped.

Instead, the stimulative impact from the much ballyhooed U.S. federal government tax cuts was short lived. Chinese economic growth slowed sharply as soon as new debt issuance was curtailed. While the eurozone has showed signs of life, it remains under constant threat, with Brexit and a potential Italian banking crisis now on the front burners. Oil prices have collapsed, and trade wars have cast a pall over everything.

Not surprisingly, forecasters ushered in 2019 with much more bearish projections, and many now predict that the second longest economic expansion in U.S. history will end in the near future. Main Street appears to concur with Wall Street’s less sanguine view – Google searches for the term “recession” are more than three times higher today than they were a year ago.

This has all happened quickly.

In October, bond-market investors were assigning 80% odds that the Bank of Canada (BoC) would raise its policy rate by 0.25% at its meeting on January 9 (this Wednesday). Today those odds have dropped to 0%. Over the same period, the futures market has gone from betting on three rate hikes by the U.S. Federal Reserve in 2019 to now pricing in no increases this year and rate cuts in 2020.

The prospect of a downturn is spooking financial markets because if countries do fall into recession (which is roughly defined as a period of negative economic growth lasting for at least six months), it will be harder to reverse than in previous cycles.

That’s because the recession-fighting tools that central banks typically rely on are now less potent. For example, the policy rates in most of the world’s developed economies still hover perilously close to 0%, and that leaves their central bankers less room to cut rates if they need to stimulate growth.

Also, most of the world’s largest central-bank balance sheets are still bloated with assets purchased under the massive quantitative easing (QE) programs that were initiated during the financial crisis. Those central banks are now trying to either stop expanding their QE programs, or in the case of the U.S., to unwind them.

Many of the experts I read believe that ending these programs and returning central-bank balance sheets back to normal will prove impossible, and they liken the exercise to trying to put toothpaste back in its tube. It will be a messy business for sure and one with no precedent for policy makers to rely on. (Side note: The BoC did not engage in any QE, but our economy will still be impacted as other central banks try to stop and/or unwind their programs.)

Even if the central banks that engaged in QE do manage to wean their economies off these stimuli, they will still have much less room for additional QE-type measures the next time recession hits. And at the same time, the huge scale of previous QE initiatives has desensitized financial markets to their stimulus effects, which means that on a relative basis, even more massive and radical unconventional monetary policies will be required to produce an equivalent impact the next time around.

Central bankers aren’t the only policy makers with more limited firepower today. Most governments in the world’s largest economies are now running significant budget deficits, and that will also limit their options for fiscal-policy responses when the next economic slowdown hits.

Bluntly put, the global economy papered over its last debt crisis with more debt. (The chart below provides a breakdown of debt accumulated by corporations, governments and households since 2008.) That helped prevent a more severe financial crisis ten years ago, but it has since fuelled asset bubbles, diminished future policy flexibility, increased instability risks, and stifled economic momentum. Today we are reaping what grew from the seeds that were planted then. The question for readers of this blog is what this all means for our mortgage rates in the year ahead.

The question for readers of this blog is what this all means for our mortgage rates in the year ahead.

Do you want the good news or the bad news first?

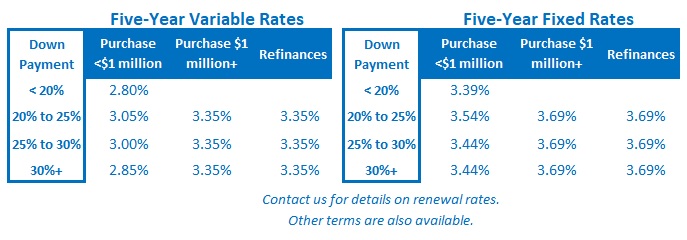

I consider myself an optimist at heart so let’s start with the good news: I don’t think that our five-year fixed and variable mortgage rates will be materially higher at the end of this year than they are now. In fact, my best guess is that both will actually be lower in twelve months.

Unfortunately, that view is underpinned by the belief that global GDP growth will slow, and more specifically, that both the U.S. and Canadian economic momentum will stall out in the year ahead. Simply put, rates have historically always fallen during a recession, so if we get hit with one this year, our mortgage rates are almost certainly headed down, not up.

To be clear, I’m not hoping for this outcome.

Whereas rising interest rates are most often a sign that a country’s economic prospects are improving, falling interest rates typically correspond with slowing momentum and provide only a thin silver lining in what are otherwise dark economic clouds.

On a related noted, if I’m wrong, I hope it is because our economic momentum proved more resilient and not because U.S. President Trump’s trade wars fuelled a spike in inflation that the BoC has already said it won’t ignore, even if growth slows.

Stay tuned.

The Bottom Line: Economic momentum is now slowing both at home and abroad. That has financial markets especially concerned because, as outlined above, policy makers will have fewer and less effective options available to fight the next downturn (which increases the odds that it will last longer than normal). While slowing growth won’t be good news for Canadians on an overall basis, it should mean that both our five-year fixed and variable mortgage rates will be lower in twelve months’ time.