Champagne Corks Pop in Response to Latest US Inflation Data

November 14, 2022Canadian Mortgage Primer: All About Trigger Rates

November 28, 2022 Last week Statistics Canada confirmed that overall inflation levelled off in October after falling over the previous three months. That was essentially in line with consensus expectations.

Last week Statistics Canada confirmed that overall inflation levelled off in October after falling over the previous three months. That was essentially in line with consensus expectations.

Our headline Consumer Price Index (CPI) held steady at 6.9% on a year-over-year basis. The biggest contributors to last month’s inflation were higher mortgage rates and prices at the gas pump, and the most notable decelerations occurred in groceries and natural gas prices.

Our core CPI, which strips out food and energy prices, rose by 5.3% year-over-year in October, marking a very slight drop from the 5.4% pace we saw in September. That said, the two sub-measures of core inflation that the Bank of Canada (BoC) is watching most closely (CPI-trim and CPI-median) both increased by 0.1%.

While we can all hope that inflation will resume a downward path soon, there are signs that it may take longer than is widely expected. Here are some examples to support that view:

House Prices – The BoC wants our housing markets to continue moderating, but any moderation will be limited beyond the short term by the record levels of immigration that our federal government is planning from here to as far as the eye can see.

Even if new immigrants are more likely to rent than buy, they will still need to be housed at a time when demand is already substantially outstripping supply. The largest urban centres, to which new immigrants tend to gravitate, already have the most significant shortages.

Developers are also cancelling projects now, which means that new housing supply will be slower to come online.

Labour Costs – Average wages rose by 5.6% in October. Because wages affect the price of just about everything, it’s hard to imagine that overall inflation will fall much below that pace. That’s why the BoC has repeatedly cited our overheated labour market among its chief concerns.

Labour Costs – Average wages rose by 5.6% in October. Because wages affect the price of just about everything, it’s hard to imagine that overall inflation will fall much below that pace. That’s why the BoC has repeatedly cited our overheated labour market among its chief concerns.

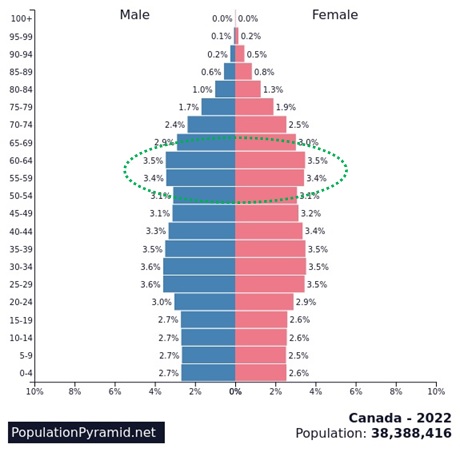

Wage prices are just about the stickiest of all costs, and their upward pressure today isn’t just a result of pandemic-related distortions. As the chart on the right shows, a large and disproportionate number of Canadians are now reaching retirement age, increasing the likelihood that our overall supply of labour will fall short of our economy’s demand for a while yet.

(And if you’re looking for a strong argument in favour of record immigration, this is it.)

Energy Prices – Energy is another pervasive cost and inflation won’t drop back into the BoC’s target band of 1% to 3% until energy prices drop materially or the prices of everything else catches up. So far, while we have seen some moderation in energy prices lately, they remain elevated.

An economist would normally expect high energy prices to lead to increased production, but that hasn’t happened (particularly with oil) to nearly the extent that will be needed to stave off more price rises as soon as energy demand resumes its upward trajectory.

Government Spending – The BoC is understandably reluctant to criticize its political masters, so I’ll do that job for them.

Our federal and provincial governments were too slow to rein in their profligate pandemic-related spending, and this failure significantly contributed to today’s rampant inflation. Disappointingly, and surprisingly, they seem to still believe that subsidies and even more spending are the best ways to deal with the consequences of previous overspending.

It’s too bad Albert Einstein isn’t here to remind them of his definition of insanity, which is doing the same thing over and over and always expecting a different result. Old habits die hard.

Corporate Profit Margins – Prices aren’t likely to moderate until our currently elevated corporate profit margins are reduced to more normal levels.

Many corporations raised their prices pre-emptively to counteract higher input costs caused by supply shortages and often by much more than would have been required to maintain previous profit margins. As a result, the US Commerce Department recently noted that US non-financial corporations reported their highest profit margins since 1950 in the second quarter of 2022.

Monetary-policy tightening and the resulting drop in demand should compel those companies to either absorb further cost increases or lower their prices going forward. But all that will take time to play out enough to significantly lower inflationary pressures.

Markets are always ruled by one of two prevailing emotions: greed and fear.

An extended period of ultra-low interest rates and government largesse encouraged greed to run amok, sowing the seeds of inflation. Now, the BoC’s rate hikes, along with stern warnings about pain being a necessary evil, have caused fear to re-emerge. Having said that, fear will need to dominate the zeitgeist before inflation can be brought to heel.

Canadians will have to spend less, unemployment rates will have to rise, house prices will have to continue to fall, and companies will have to become more concerned about selling excess inventories than they are about maintaining their unusually high margins.

We’re still a long way from reaching that point, and the factors outlined above lead me to believe that this process will take longer to play out than most forecasters currently project.

I also think that the BoC will tolerate more economic pain this time around.

Central bankers waited too long to raise rates, and that compels them to be much more pro-active at this point in the cycle. The consequent danger is that they will now err on the side of over overtightening. That assumption underpins my belief that the Bank will leave its policy rate at an elevated level for longer than the market is currently expecting. It also explains why I expect the BoC to lower its rate rapidly when it judges that inflation’s back is finally broken.

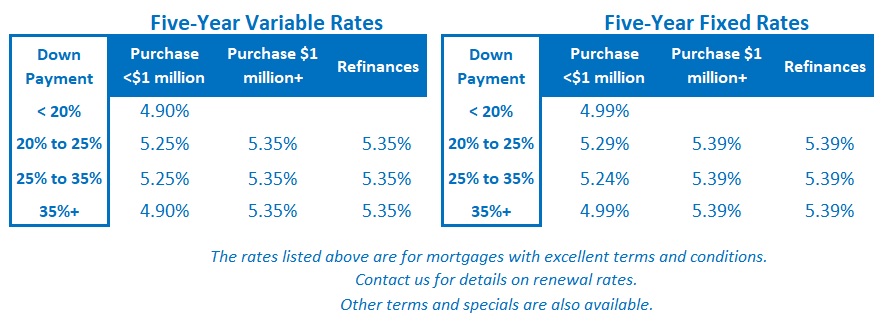

If you’re in the market for a mortgage today, here are your options:

Variable rates: Variable mortgage rates will almost certainly continue to rise over the near term, and at today’s levels, or higher, they will likely be more expensive then their fixed-rate equivalents for the next year or two. But farther into your term, if you subscribe to my overall view, they could fall quite rapidly. If that happens, variable rate borrowers will benefit immediately.

Short-term fixed rates: Shorter-term fixed-rate mortgages of two to three years provide more near-term security than variables. They also provide the opportunity to reset the rate sooner than would be the case with longer-term fixed-rate options. These shorter-term fixed-rate mortgages are well worth considering if you are willing to accept the risk that your renewal date will arrive before lower rates materialize.

Five-year fixed rates: These are now among the lowest rates available, and while you would be locking in after the sharpest run in rates in more than four decades, this option protects you against the risk that inflation takes much longer to abate than most currently expect. (Just make sure your mortgage contract doesn’t come with a huge prepayment penalty that will effectively block you from refinancing if rates drop significantly – as this post explains.)

The Bottom Line: Government of Canada bond yields held steady last week, and lenders have started to drop their fixed rates in response. I expect that to continue in the week ahead as the market continues to reset at these lower levels.

Variable-rate discounts were unchanged last week, and the future market is pricing in a 0.25% rate hike by the BoC at its next meeting on December 7, despite learning that inflation pressures did not cool in October.