Was the US Federal Reserve’s Most Recent Hike Really That Dovish?

February 6, 2023Top Five Recent Posts About Mortgage Rates and Inflation

February 21, 2023 Last week we learned the Canadian economy added an estimated 150,000 new jobs in January, ten times higher than the consensus estimate of 15,000. Average hours worked also increased by 0.8%.

Last week we learned the Canadian economy added an estimated 150,000 new jobs in January, ten times higher than the consensus estimate of 15,000. Average hours worked also increased by 0.8%.

The Canadian employment upside surprise arrived on the heels of a blowout US employment report (which I wrote about in last week’s post). As a reminder, the US economy added 517,000 new jobs versus the consensus estimate of 185,000. US average hours worked also increased.

While the initial employment data are volatile and are often subsequently revised, labour demand is clearly still stronger than expected on both sides of the 49th parallel.

Bond-market investors responded to our latest employment data by adjusting their bets on the Bank of Canada’s (BoC) policy-rate path for the balance of this year. Until last Friday, investors had been pricing in two quarter-percentage point cuts, but now they are betting that the Bank’s policy rate will either stay where it is or, less likely, rise by an additional quarter point.

Regular readers of my posts will have noted my frequent warnings that inflation may take longer to return to target than the consensus expects because wages have grown at about 5% on a year-over-year basis for eight consecutive months now.

BoC Governor Tiff Macklem underlined that very point in a speech last week when he acknowledged that “the labour market is very tight” and then bluntly conceded that “if the labour market stays this tight, we’re not going to get back to 2-per-cent inflation.”

It’s certainly hard to imagine how inflation can fall back to its 2% target when average wage costs, which pervade our entire economy, are rising at well above that level. Especially when you consider that elevated wage-growth rate hasn’t even preserved the purchasing power of the average worker – and that this has been happening at a time when the demand for labour is still outstripping its supply. The current backdrop is giving many workers both the motivation and the leverage they need to push for increased wages.

(It’s true that the rate of average wage growth dropped from 4.8% in December to 4.5% in January on a year-over-year basis, but that drop was attributed to a one-time base effect tied to the wage data twelve months ago. Average wage growth can be expected to rebound when Stats Can releases its next report – for February.)

Some market watchers continue to subscribe to the view that the Canadian and US economies will be able to pull off a soft-landing, wherein a return to target inflation is achieved without requiring a recession. They support that view by citing the fact that inflation has fallen from its peak while employment growth has remained robust. While it is a good argument based on our recent data, there is no guarantee that the same dynamic will hold going forward.

Inflation has indeed fallen from its peak, but that was mostly a result of normalizing supply chains and cooling energy prices, and both developments were largely attributed to foreign factors. An increasing proportion of our current inflation pressure is now coming from domestic sources, such as services, which are heavily impacted by labour costs. Put simply, while the drop in inflation from 8% to 6% didn’t require a sharp drop in labour demand, getting inflation from 6% down to 2% most certainly will.

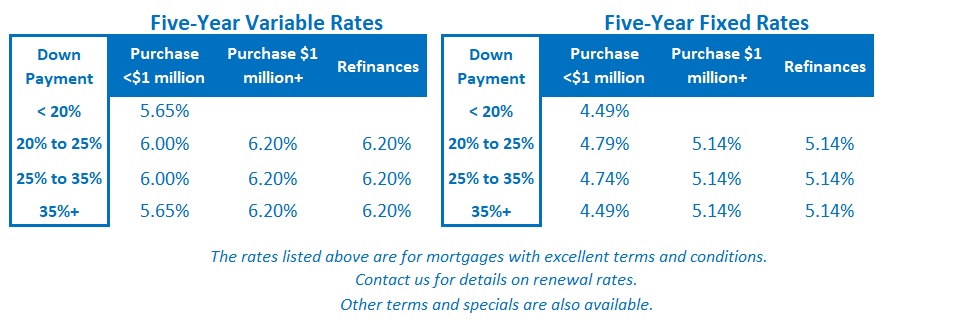

For the reasons outlined above, I continue to believe that opting for a variable rate today should be seen as an aggressive bet. This is not because I think the BoC will raise its policy rate materially higher but because I expect that it will need to hold it at or even above today’s level for longer than most market watchers currently expect.

Variable-rate borrowers starting a new term today must be willing to initially pay an interest-rate premium of about 1% above the available fixed-rate equivalents. Anyone who does that today is making the bet that their rate will drop by enough over their full term to recover that initial premium (and then some). The total that they pay will be determined by two factors: 1) how long it takes before variable rates start to drop, and 2) how low they ultimately go before the term of their mortgage ends.

While I don’t think it is unreasonable to bet that today’s five-year variable rates may end up being cheaper than their fixed-rate alternatives over their full term, I think the odds are increasingly tilting against that probability.

At this point, opting for a fixed rate is clearly the safer middle-of-the-road pick.

On that note, I think today’s three-year fixed rates offer the best combination of near-term protection and competitive pricing. Three years should be plenty of time for our central bankers to wrestle inflation down to target – and three-year fixed rates don’t carry the significant premium that you have to pay today for one- or two-year fixed-rate terms. The Bottom Line: Government of Canada bond yields surged steadily higher last week. Initially that was on the back of US Treasury yields, which rose in response to the latest US employment data, and then on Friday in response to the latest Canadian employment data.

The Bottom Line: Government of Canada bond yields surged steadily higher last week. Initially that was on the back of US Treasury yields, which rose in response to the latest US employment data, and then on Friday in response to the latest Canadian employment data.

If that momentum continues into this week, borrowers should expect lenders to start raising their fixed rates soon.

Five-year variable-rate discounts were unchanged last week. While I don’t think last Friday’s robust employment report will cause the BoC to alter its plan to pause additional rate hikes over the near term, it does bolster my view that we are unlikely to see rate cuts in 2023.