How Will Reduced Business Confidence Impact the Bank of Canada’s Outlook?

April 22, 2019Why Our Latest GDP Data Make the Bank of Canada’s Latest Forecast Seem Bullish

May 6, 2019 Bank of Canada (BoC) economic forecasts have consistently erred on the bullish side over the past many years.

Bank of Canada (BoC) economic forecasts have consistently erred on the bullish side over the past many years.

The Bank’s typical Monetary Policy Report (MPR) acknowledges that current conditions are weaker than expected but then makes the case that they are soon to improve. Wash, rinse, repeat.

The BoC’s hope for better days is not without some foundation. For example, low levels of unemployment can trigger a virtuous, self-reinforcing cycle where robust wage growth leads to increased consumer spending, which then spurs a rise in business investment that stimulates more job creation, etc.

Only things haven’t worked out that way.

Ultra-low unemployment hasn’t fuelled the kind of broad-based wage growth that our policy makers expected to see. We have had increased consumer spending, but it’s been fuelled by rising debt rather than rising incomes – and debt is really just future consumption brought forward. Business investment hasn’t materialized as hoped, and there is little evidence of any self-reinforcing cycle.

Further, I think the BoC’s consistently optimistic forecasts may have actually hurt our overall economic momentum. Whereas the Loonie should weaken as our economic conditions deteriorate, the Bank’s bullish bias has helped to prop it up, and that has diminished a potential tailwind for our exporters. (These are the same exporters that the BoC is hoping will serve as one of our main economic growth engines going forward.)

When the BoC met last week, it left its monetary-policy rate unchanged, at 1.75%, as was universally expected. More importantly, the Bank removed any reference to future rate hikes and instead acknowledged that “monetary policy needs to maintain a degree of accommodation … until the economic outlook improves.”

Translation: We’re going to be here for a while.

True to form, the BoC once again predicted “that the economy will pick up in the second half of the year”. Frustratingly, and once again, it didn’t make a compelling case for how this will happen.

The Bank’s bet on a quick recovery is based on the beliefs that: 1) oil-sector investment will at least stop falling (fair enough), 2) exports and business investment will recover (where have we heard that before?), 3) “strong” wage gains (that are now only averaging 2.1% and barely outpacing our current inflation rate of 1.9%) will fuel a consumer spending resurgence, and 4) the negative impacts from higher mortgage rates, non-resident real estate taxes, and the mortgage rule changes will dissipate (good luck finding anyone in the mortgage business who shares that view).

Here are more detailed highlights from the BoC’s latest announcement, followed by my take on how the Bank’s evolving outlook is likely to impact our fixed and variable mortgage rates:

- The BoC acknowledged that the slowdown in global economic growth in the latter part of 2018 was “greater than expected” and it attributed this in large part to uncertainty arising from “trade policy conflicts”. The Bank lowered its projections for global GDP growth from 3.4% to 3.2% in 2019, and from 3.4% to 3.3% in 2020.

- The BoC observed that U.S. economic growth was “healthy” and was supported by “solid employment gains … rising wage growth and elevated consumer and business confidence”. Nonetheless, the Bank expects U.S. GDP growth to slow “to around 2.25% in 2019 and further to about 1.75% in 2020 and 2021” as the positive impacts of past fiscal stimuli wane and the negative impacts from past interest-rate increases continue to materialize.

- The BoC noted the recent yield-curve inversions in both Canada and the U.S. (which occurred when the yield on 10-year government bonds fell below the yield on three-month treasury bills). While this event has often preceded recessions in the past, the Bank predicted that this time would be different because the inversions were being caused by longer-term rates coming down instead of by shorter-term rates moving up. (Nonetheless, an inverted yield curve is never a normal or healthy signal for an economy.)

- The BoC lowered its forecast for our GDP growth rate sharply in 2019, from 1.7% to 1.2%. Surprisingly, it left its previous forecast for 2020 unchanged, at 2.0%, so clearly the Bank is once again expecting a steady resurgence for our economy heading into next year.

- The BoC lowered its estimated neutral-policy-rate range from 2.5% to 3.5% down to 2.25% to 3.25%. (As a reminder, the neutral-rate range is defined as the policy-rate level that neither stimulates nor slows economic growth.) That means that our current policy rate of 1.75% isn’t as far away from neutral as previously believed. Put another way, when the BoC does start raising rates again down the road, this downward range revision is an indication that it won’t have to raise by as much as it previously expected.

In its closing statement, the BoC made clear its plans to keep its policy rate at its current stimulative level to offset “various headwinds until the economic outlook improves”. It made no reference to the timing of future rate increases and instead reiterated that it would remain data dependent. Specifically, it will closely monitor “developments in household spending, oil markets, and global trade policy to gauge the extent to which the factors weighing on growth and the inflation outlook are dissipating.”

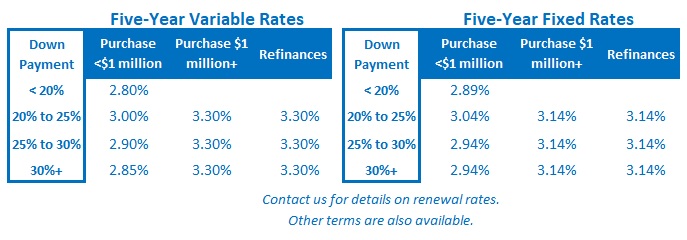

Five-year Government of Canada bond yields dropped in response to the BoC’s dovish announcement and the downward revisions to its MPR forecasts. Against that backdrop, fixed mortgage rates are now likely to either hold steady or move a little lower.

Five-year variable rates remain unchanged, and while the BoC isn’t yet conceding that its next move may be a cut if conditions don’t improve as expected in the second half of this year, I think that is a realistic possibility. If you’re considering a variable rate today, the challenge is that the discount off of equivalent five-year fixed rates is miniscule, so BoC rate cuts will need to occur before any material saving is achieved.

The Bottom Line: The BoC held rates steady last week, as expected, and more tellingly, it conceded that our current slowdown is likely to last longer than previously expected. The Bank remains optimistic that our economic momentum will rebound in the second half of this year, but for the reasons outlined above, I think that view is founded more on hope than on hard data. Variable mortgage rates were unchanged last week, and I continue to believe that the BoC’s next move is more likely to be a cut than a raise, while fixed mortgage rates are also likely to remain lower for longer in response to the Bank’s more dovish outlook.

2 Comments

Hi David, I have been following your blogs regularly since the last few months. They are very informative. I think you have been predicting the state of the Canadian economy pretty accurately. Looking forward to your next blog.

Regarding the yield inversion section in this blog, is the 10 year yield compared against three months or three years?

Hi Gurpratap,

Thank you for your email and glad to hear that you have been enjoying my blog.

In answer to your question, both of the U.S. and Canadian 10-year government bond yields recently fell below the yields offered for three-month treasuries.

Best,

Dave