Why the Bond Market Yawned at Canada’s Banner January Employment Headline

February 11, 2019Will the Bank of Canada Put Rate-Hike Speculation to Rest?

March 4, 2019 You can’t always get what you want

You can’t always get what you want

But if you try sometime you find

You get what you need

– The Rolling Stones

Last week Bank of Canada (BoC) Governor Poloz made a speech that reminded me of those lyrics.

Bluntly put, he clearly wants to raise rates but he needs to keep inflation stable.

There are factors beyond Governor Poloz’s control that are preventing him from raising the BoC’s policy rate to a neutral-rate level, which is defined as the level that neither stimulates nor restricts economic growth.

He knows that if he ignores these factors and raises the policy rate too quickly, it will unleash deflationary forces that could push inflation well below the BoC’s 2% target.

If you’re keeping an eye on mortgage rates, Governor Poloz’s speech, titled “The Power – and Limitations – of Policy”, included valuable insights into where rates may be headed over the short and medium term. I will highlight these and offer my own accompanying commentary in today’s post.

The Bank influences inflation by lowering or raising interest rates to heat up or cool down the economy … [but] our policy actions take time to have their full impact – up to two years.

The BoC began to raise its policy rate for the first time in more than seven years in July 2017. At that time our economy was gathering speed, and the Bank believed it had a window to begin raising its policy rate back into its neutral-rate range, which the BoC now estimates is between 2.5% and 3.5%.

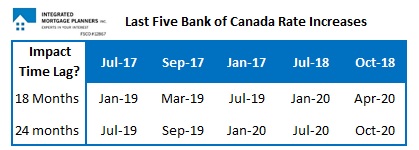

The Bank has added another four 0.25% rate hikes since then, and if it takes two years for each hike to assert its impact, the full bite from the first hike won’t be realized until July 2019 (here is another look at the chart I posted recently ).

This timing is likely to give the BoC pause because while our economic prospects were improving in 2017, they are decidedly weaker now. To wit, our GDP shrank by 0.1% in November (which is the most recent result available), our export sales have fallen steadily over the past six months, and business investment and consumer spending have both slowed. (At the same time, growth is moderating across the world’s largest economies and geopolitical uncertainties abound.)

A crucial feature of this framework is that we have just one policy instrument: our influence over interest rates. This represents the first major limitation on the power of monetary policy. With only one instrument, we can aim at only one objective … ultimately, inflation is the sole target of the policy.

When we think of the BoC fighting the inflation battle, we instinctively imagine rising inflation as the threat, but the Bank must also manage against falling inflation, and that can actually be a much more difficult job.

Rising inflation can always eventually be reined in with rate hikes. The impacts are painful but largely predictable. Conversely, when inflation is falling, or worse, it turns into outright deflation, central banks would ideally cut their rates in response. But when those rates are already at or near 0%, that option doesn’t exist, and central banks turn to more experimental options.

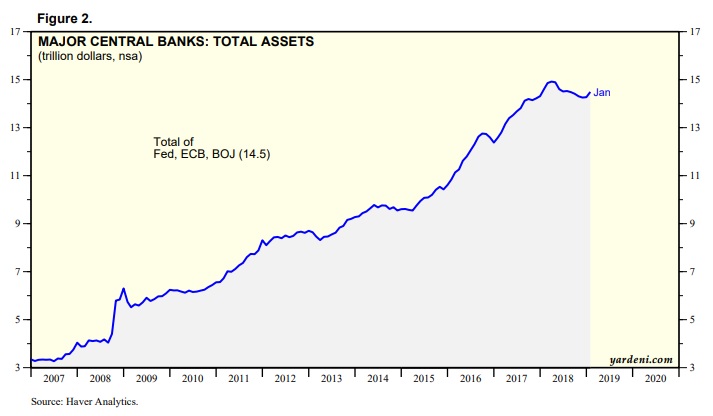

During the financial crisis, for example, many central banks invoked unconventional monetary policies, like quantitative easing (QE), on an extraordinary scale. (See chart below showing what that did to the balance sheets of some of the major central banks.)

Strangely, when viewed in the context of conventional wisdom, even when these eye-watering levels of QE were combined with massive rounds of deficit-financed fiscal stimulus, inflation stayed below 2% in all of the G7 countries (Germany, France, Japan, Canada, Italy, the UK and the U.S.).

Now we are left to wonder: “If inflation barely showed a pulse through that period of ultra-low interest rates, massive QE programs and generous fiscal stimulus, where is it likely headed now that many of the world’s largest central banks have used up most of their ammunition?”

Long-term factors like aging demographics, high debt levels and technological improvements are exerting downward pressure on inflation in most of the world’s advanced economies (which I have written about in past posts). These combined forces have thus far counteracted the stimulative efforts of central bankers and governments. But if those policy-rate and fiscal stimuli are now reduced or withdrawn, deflationary forces are likely to reassert themselves. If that happens, the BoC will once again be more worried about deflation than inflation, and that will portend lower rates, not higher ones.

A symptom of our success is the fact that many people do not appreciate how problematic high and variable inflation and interest rates can be. This is a gift to the next generation, if you will. My children will never pay anything like the kind of interest rates I have paid in my lifetime.

I regularly encounter first-time buyers who have been warned by their well-meaning parents about interest rates of 20%+ , on the theory that if they happened once, they can happen again.

Thanks to inflation targeting (which was introduced by the BoC in 1991), and a whole host of other factors, I do not believe that fears of 20%+ interest rates should be guiding borrowers’ decision-making process today.

Rates could certainly move higher, and even materially so, but I do not believe that we will again see the levels that still give nightmares to older generations.

In pursuing our inflation target, we may create side effects that make the economy vulnerable to new shocks. This is what happened during the Great Moderation, and it is what has happened during the recovery from the global financial crisis. Of course, the fact that we have only one policy instrument means that we cannot independently try to manage those side effects without putting our inflation target in jeopardy.

During the financial crisis, the BoC knew that the monetary policy it needed to adopt to keep inflation stable would increase the potential for financial shocks like housing bubbles. (I well remember when BoC Governor Mark Carney publicly implored federal finance Minister Jim Flaherty in 2010 to introduce mortgage rule changes to mitigate against that risk.)

If the BoC is steadfastly committed to adhering to its inflation target, even if it triggers imbalances elsewhere in the economy, and if the inflation data call for continued low rates, that’s what we should expect. If house prices start to bubble again, expect more mortgage rule changes, not higher rates.

(Incidentally, anyone who works in real-estate related industries should be thanking our regulators for mitigating the housing bubble risks that were created by the BoC’s ultra-low rates. By now it should be obvious that they saved us from a much worse fate.)

One important uncertainty that we are dealing with today is the impact of higher interest rates on highly indebted Canadians. Rising interest rates will mean these people will have to spend more of their income servicing debt, leaving less for other goods and services. Clearly, given these elevated levels of debt, raising rates will have more of an impact on the overall economy than in the past.

As the BoC says above, the recent rate rises are expected to have more of an impact on our economic momentum than in the past. Again, the first of the five increases will reach its full impact only this summer. And the data say that our economic momentum is already slowing as we brace for that coming headwind.

We must acknowledge that the future of the global trade environment is highly uncertain right now … [and] given these uncertainties, we have kept interest rates unchanged at 1.75 per cent since last October. We will remain decidedly data-dependent as the domestic and international situations evolve.

In the face of so much “uncertainty” (Governor Poloz used that phrase a total of eight times in his speech), it makes sense that the BoC wants to allow time for things to “evolve”. But the kind of evolution the Bank is looking for is more likely to take place over quarters and years, not weeks and months, and that’s why I think the BoC has finished raising its policy rate for now.

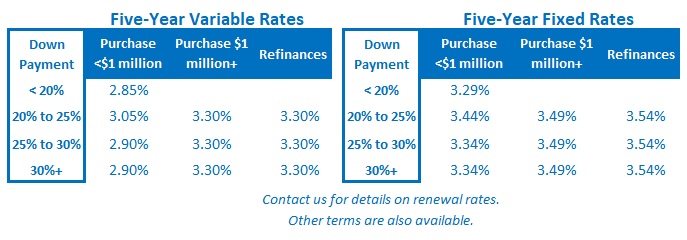

The Bottom Line: BoC Governor Poloz wants to raise the Bank’s current policy rate of 1.75% into its target neutral-rate range of 2.5% to 3.5% sooner rather than later. But first he needs the data to confirm that our inflation trajectory can withstand additional hikes. I think it will take a while for that to happen, and if I’m right, our fixed and variable mortgage rates are more likely to go down than up in the months ahead.

The Bottom Line: BoC Governor Poloz wants to raise the Bank’s current policy rate of 1.75% into its target neutral-rate range of 2.5% to 3.5% sooner rather than later. But first he needs the data to confirm that our inflation trajectory can withstand additional hikes. I think it will take a while for that to happen, and if I’m right, our fixed and variable mortgage rates are more likely to go down than up in the months ahead.