Why Mortgage-Rate Rises Are About to Pack More Punch

March 21, 2022Is the Bank of Canada about to Hike by 0.50%?

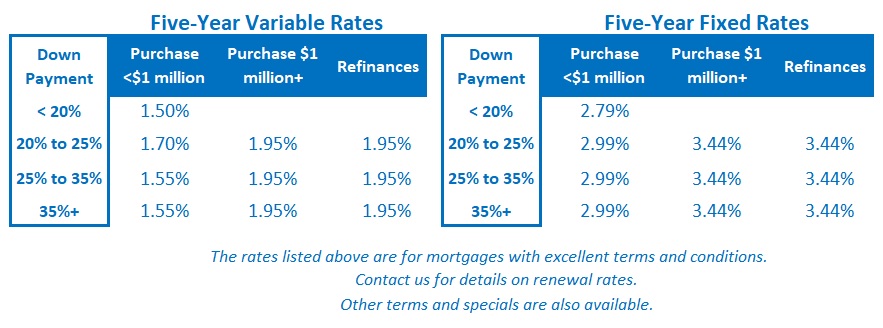

April 4, 2022Five-year fixed-mortgage rates continued their rise last week, driven higher by the spiking five-year Government of Canada (GoC) bond yield (which closed at 2.51% on Friday, marking its highest level in more than ten years) and by new market-risk premiums that materialized in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

To put that statement in context, five-year fixed-rate mortgages with 30-year amortizations were available at about 2.50% in January and are now offered at rates about 1% higher. If they continue to rise at their current pace, five-year fixed rates could easily exceed 4% by Easter.

For the first time in years, as I wrote in last week’s post, affordability is now being impacted because fixed-rate borrowers must qualify at the greater of either the current stress-test rate of 5.25% or the contract rate + 2%. As five-year fixed rates rise above 3.25%, the contract rate + 2% exceeds the current stress-test rate of 5.25% and becomes the higher rate used for qualification.

Variable rates + 2% are still well below 5.25%, but the Bank of Canada (BoC) is expected to hike its policy rate repeatedly this year, so the current gap between five-year fixed and variable rates, which is still about 1.5%, will narrow.

Anyone in the market for a mortgage now must decide between two quite different types of risk.

- Five-year fixed-rate borrowers must accept the risk that they could be locking in a rate that has been temporarily elevated by spikes in both bond yields and risk premiums, which are likely to subside before the end of their mortgage term.

Stubbornly high, above-target inflation has elevated our bond yields primarily due to temporary pandemic-related factors.

Lockdowns led to supply shortages while governments pumped massive amounts of fiscal stimulus into their economies, supercharging demand. Against that backdrop, the inflation spike that followed did not come as a surprise.

Those emergency stimulus payments have now stopped, and while it took more time than initially expected, supply bottlenecks are slowly being rectified. Those developments led many to believe that inflation would start to cool in the early spring of 2022, and the bond market appeared to share that view – yields had moved steadily higher but were still largely contained.

Then Russia invaded Ukraine, and many commodity prices, most notably oil, gas, and food, went through the roof. Bond-market investors had seen enough, and that was the point when the current sell-off that has pushed the GoC five-year bond yields from 1.50% to 2.50% (thus far) began in earnest.

The question now is whether we have entered a new era of steadily rising bond yields or whether this is just a short-term blip before we revert to our economy’s long-term trends of low growth, low inflation, and low rates.

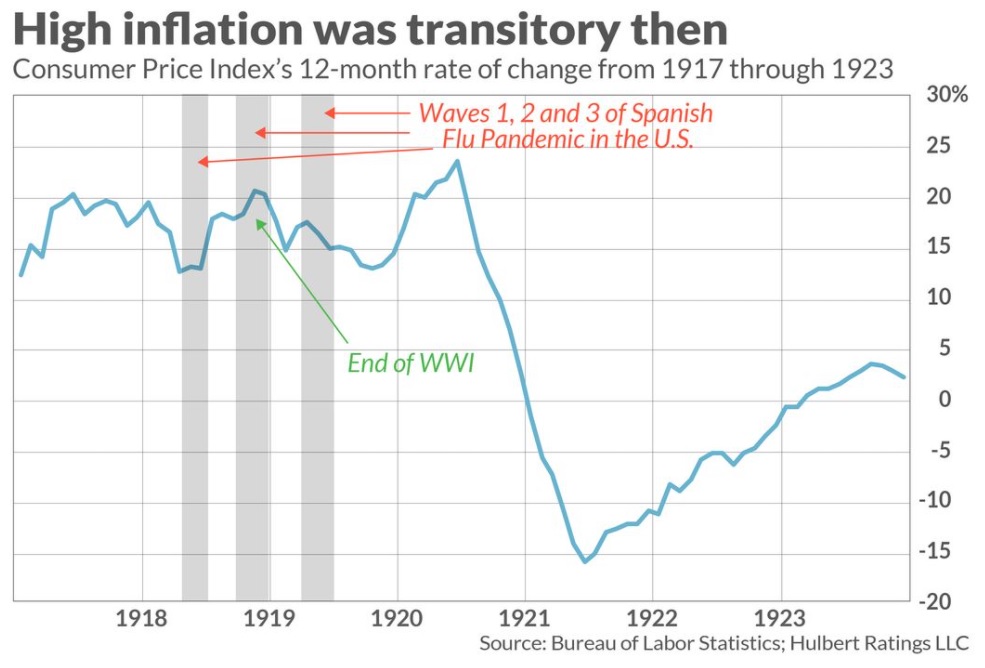

To shed some light on that question, let’s go back to the last time we had the dual shock of a war and a pandemic. That was the period from 1917 to 1923.

The following chart shows inflation averaging between 15% to 20% over the period from 1917 to 1920, before plunging to negative numbers in 1921-1922, and then hovering in the 2% range for the decade that followed. There is no guarantee that past is prologue, but it seems reasonable to assume that the sources of today’s inflation pressures will eventually subside, and when they do, inflation could fall dramatically – along with bond yields, and the mortgage rates that are priced on them. (On that note, economist David Rosenberg recently noted that oil price futures one year out are already priced 20% lower than today’s spot price.)

There is no guarantee that past is prologue, but it seems reasonable to assume that the sources of today’s inflation pressures will eventually subside, and when they do, inflation could fall dramatically – along with bond yields, and the mortgage rates that are priced on them. (On that note, economist David Rosenberg recently noted that oil price futures one year out are already priced 20% lower than today’s spot price.)

We also saw an example of a mortgage rate run-up and subsequent blow-off when the pandemic first started.

In early February 2020, five-year fixed rates with 30-year amortizations were offered in the high 2% range. Then COVID hit, and borrowers jammed the phone lines trying to defer their mortgage payments. Lenders responded by adding risk premiums that pushed those rates into the low 3% range by April 2020. But by July, once the dust had settled and doomsday fears had subsided, those five-year fixed rates had dropped into the low 2% range. Ultimately they fell all the way into the high 1% range by early 2021.

Borrowers who opted for 3%+ five-year fixed rates in the spring of 2020 locked in at a high. If they borrowed from a lender who charges fair penalties, they then had to break their mortgage in order to take advantage of the ensuing rate drop, but if they borrowed from a high-penalty lender, they were effectively blocked from receiving any net benefit by their mortgage contract’s onerous terms (as this post explains).

- Variable-rate borrowers are taking the risk that the BoC will hike by more than expected.

The inherent risk in a variable-rate mortgage is more easily understood. There is technically no limit to how high variable rates can go, and the BoC has made it clear that it will do whatever it takes to bring inflation back to target.

Anyone taking a five-year variable-rate mortgage today will start with a buffer about 1.50% below the currently available five-year fixed-rate equivalents.

The bond-futures market expects that buffer to all but disappear by the end of this year, but it is also pricing in rate cuts in 2024 under the assumption that the BoC will overtighten and drive our economy into recession. (That risk is exacerbated in the current environment because the impact of each rate hike will be magnified by record-high government and household debt levels.)

Forecasting the number of BoC rate rises is extremely difficult now because today’s inflation is the result of supply shortages, which policy-rate hikes can’t directly address. Instead, the Bank will use rate hikes to bring demand down to meet supply at its currently impaired levels.

If we’re trying to figure out how many rate hikes it will take before a supply/demand balance is restored, it is important to note that other factors are already doing some heavy lifting in this regard.

For example, the recent sharp run-up in fixed mortgage rates is impacting our economy in much the same way that BoC rate hikes otherwise would and is therefore providing its own form of (significant) monetary-policy tightening.

At the same time, food and energy are essential costs, and their price increases act like a tax on other more discretionary types of spending. On that note, last week a National Bank economist estimated that the impacts from our recent food and energy price spikes could end up being equivalent to three 0.25% hikes by the BoC.

The points above don’t provide variable-rate borrowers with any certainty about what will ultimately unfold. However, when bond yields appear to be pricing in worse-case scenarios and the mainstream media are warning borrowers to lock in at whatever rate they can get, now seems like a good time to remind my readers that the fixed/variable decision comes with risk no matter which choice is made.

Borrower beware. The Bottom Line: Five-year GoC bond yields and the five-year fixed mortgage rates that are priced on them continued their dramatic rise last week. Without any apparent catalyst to stop or reverse this upward momentum, anyone considering this option should be locking in a rate as soon as possible.

The Bottom Line: Five-year GoC bond yields and the five-year fixed mortgage rates that are priced on them continued their dramatic rise last week. Without any apparent catalyst to stop or reverse this upward momentum, anyone considering this option should be locking in a rate as soon as possible.

Five-year variable rate discounts also continued to shrink last week as lenders adjusted their rates to include premiums for geopolitical and financial stability risk.

Variable rates are most definitely headed higher, and there is even speculation that the BoC could hike by 0.50% instead of 0.25% at its next meeting. But for the reasons outlined above, I continue to think there is a good chance that variable rates will prove cheaper than their fixed-rate equivalents over the longer term.