Has the Bank of Canada’s Policy Rate Finally Peaked?

December 12, 2022Five Posts to Kick Off the New Year

January 3, 2023What a long, strange trip 2022 has been.

At the start of the year, who would have believed that we would now be happy to learn that Canadian and US inflation rates were holding steady at about 7%? Or that we would be relieved, after the sharpest increases on record, when the Bank of Canada (BoC) and the Fed hiked by only 0.50% at their final meetings of the year?

2022 will go down as the year the free money era ended. Wherever we are headed next, the only certainty is that it won’t be back to interest rates that start with the digit “1” any time soon.

Here are my final and most important observations about our current interest rate environment as we head into 2023:

- Financial markets are pricing in central-bank pauses on both sides of the 49th parallel, but both the BoC and the Fed continue to tell anyone who is still listening that their policy-rate decisions will be dictated by whatever the inflation data require, regardless of any concomitant economic pain.

- In fact, if the BoC and the Fed have any current bias, it is toward over-tightening for two key reasons. First, both central banks left their policy rates too low for too long when the pandemic ended and that decision caused much of the current inflationary damage. Second, they are fully aware that the last time inflation ran amok, in the late 1970s, their predecessors cut their policy rates too soon, fueling a second-wave inflation spike that peaked at a higher level than the first one. We should expect them to learn from history to avoid repeating it.

- It will be much easier for tighter monetary policy to bring inflation down from 6% to 4% than it will be to get it down from 4% to anywhere near 2%. The biggest inhibitor will be labour costs, because they are pervasive and act like a ratchet on other prices. Canadian year-over-year wage growth has been above 5% for the past several months, and that cost surge can be attributed, at least in part, to a structural shortage of qualified labour that tighter monetary policy can’t materially impact. Wage growth will be hard to rein in, and we shouldn’t expect inflation to drop much below our rate of average wage growth for any sustainable period.

- For all the talk about higher rates slowing growth and possibly triggering a recession, we haven’t yet felt the effects of higher rates across the broader economy. Consumers are still spending, near-term inflation expectations remain high, and companies have not yet been compelled to cut prices. All of that will need to change before we see any potential rate cuts. Simply put, I started the year (admittedly stubbornly) holding on to a lower-for-longer rate view, but over the ensuing twelve months, the data have forced me (and the Fed and the BoC) into the higher-for-longer rate view that I now hold.

- For the reasons outlined above, I don’t think that inflation, and therefore mortgage rates, will retreat as quickly as many expect. Instead, I expect that the BoC and the Fed will use their monetary policies to constrict the demand sides of their economies until inflation has been fully vanquished. Sticky wages and prices will prolong that process. That said, once inflation is finally brought to heel, I expect a series of rapid rate cuts as the BoC tries to breathe life back into whatever is left of our economic momentum. I don’t believe we’ll get back to the low rates we saw during the pandemic, but I do expect rates to drop enough to provide meaningful relief (and saving) to variable-rate borrowers.

As we head toward the challenges that we know 2023 has in store for us, I will close by expressing my gratitude to you, my reader, for your ongoing interest (pun intended!) in my weekly Monday musings.

Have a safe and happy holiday season.

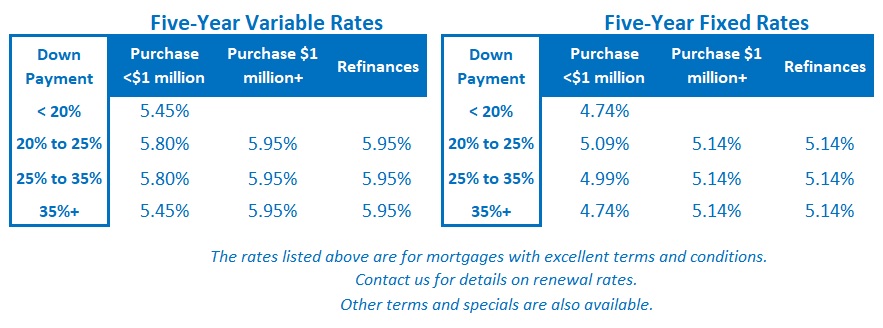

The Bottom Line: Government of Canada bond yields drifted lower again last week. Fixed mortgage rates also continued to drop. There is still more air under those rates for lenders to work with, so they will likely fall further over the near term.

Five-year variable rate discounts were unchanged last week. Variable rates are now considerably (and unusually) higher than fixed rates, and that has significantly diminished their appeal for now.