The Fed Raises and Warns It Isn’t Done Yet

September 26, 2022Five Mortgage-Rate Thoughts from Last Week

October 11, 2022

Monetary policy provides a powerful tool for our central bankers to use during tough times.

Monetary policy provides a powerful tool for our central bankers to use during tough times.

Lowering short-term policy rates helps to stimulate economic growth, and central-bank balance sheets can be used for myriad purposes, which include restoring market liquidity and influencing or even outright manipulating longer-term bond yields and borrowing rates. But, human nature being what it is, over time, that blessing became a curse. The ability to do something seems to have made our central bankers forget that sometimes the best option is to do nothing.

Ever since the US financial crisis of 2008, the US Federal Reserve and to a lesser extent the Bank of Canada (BoC), have used monetary-policy tools to counteract seemingly any and all negative economic forces when they could be seen on the horizon. Financial market participants grew accustomed to the idea that the Fed (and the BoC) would blunt any negative shocks which occurred. That belief evolved to the point where bad news for Mainstreet was interpreted as good news for Wall Street and Bay Street because it meant that looser monetary policy would soon follow.

That approach was never going to work over the longer term because free-market economies rely on creative destruction, which occurs when less efficient businesses and methods are destroyed by more efficient and innovative alternatives. This evolutionary process ensures a messy and imperfect environment where economic pain is an unavoidable consequence for some participants, but it also fosters constant improvement that leaves the overall economy better off in aggregate.

Increasingly over the past two decades, our central bankers have managed to counteract much of the economic pain that would have otherwise occurred. But they didn’t eliminate the pain – they just pushed it into the future and bought their economies some time.

As each threat passed, our central banks were too slow to remove their monetary-policy accommodations, and much of it was often still in place by the time the next dark cloud appeared on the horizon. That meant that each new round of monetary-policy stimulus had to be administered in increasingly larger doses to produce a similar impact.

To use an analogy, consider what happens to a forest when every small fire is suppressed wherever we have the ability to overwhelm it. That seems like a good strategy in one-off cases, and it works well for a while. But eventually the lack of small fires causes the dead wood to accumulate until it becomes fuel for larger, more severe fires that are much more difficult to control.

Loose monetary policy has reduced the amount of creative destruction in our economies and has allowed “zombie companies”, which should have failed but didn’t, to pile up like the deadwood in the forest. Now that rampant inflation has backed our central bankers into a corner. They have no choice but to raise policy rates and are telling anyone who will listen that this time, they are going to let the fires burn.

As a response to rising rates, our economies are now starting to slow, and both the Fed and the BoC have warned that pain will be necessary, whether it be business failures, job losses, falling house prices, or all of the above.

Rampant inflation and the need for much tighter monetary policy are now global phenomena, and the consequent strains will test the weakest areas the most. We see many examples of this today, including wild currency fluctuations, plummeting stock markets, the teetering of global banks such as Credit Suisse and Deutsche Bank, and last week’s run on UK government bonds in response to the British government’s desperate attempts to defibrillate its faltering economy.

Now let me explain how all of the above impacts my outlook for Canadian mortgage rates over the next few years (with the important caveat that forecasting where rates are headed is always a best guess and not a promise).

Over the near term, I don’t expect the Fed or the BoC to stop raising their policy rates until they see inflation start to drop materially, even though it is a lagging indicator that they are trying to tamp down with rate hikes that will take up to two years to exert their full bite. Simply put, we’re in this current mess because our central bankers kept their rates too low for too long, and the associated hit to their credibility will leave them bound and determined to err on the side of overtightening this time around.

That assumption, combined with the fact that inflationary pressures have continued to broaden throughout the economy of late, underpin my belief that mortgage rates are going to remain higher for longer than I expected earlier this year. But those factors also bolster my belief that we’re also in for a sharper and more prolonged downturn that will, of necessity, lead to more substantial cuts when inflation is finally brought to heel.

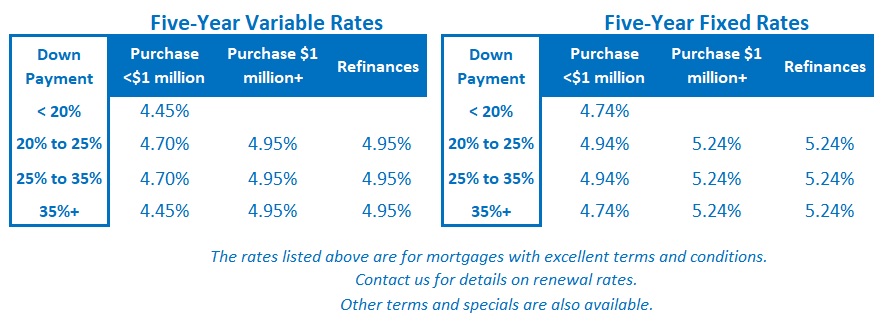

All told, I think today’s five-year variable rates are still a good bet to save money when compared to their fixed-rate equivalents over their full typical five-year terms, even if they are a little more expensive at the outset. Alternatively, if the heightened volatility (and uncertainty) of our current backdrop will cost you too much sleep, shorter-term fixed rates, and five-year fixed rates that don’t come with onerous break penalties, will allow you to come back to the market if rates fall in future years, as I expect it will.  The Bottom Line: Fixed rates rose last week, as I warned they might in last week’s post. With so much near-term volatility, it is increasingly difficult to forecast rate movements over the immediate term, but for the time being, it is safest to assume that the momentum arrow is still pointed up.

The Bottom Line: Fixed rates rose last week, as I warned they might in last week’s post. With so much near-term volatility, it is increasingly difficult to forecast rate movements over the immediate term, but for the time being, it is safest to assume that the momentum arrow is still pointed up.

Five-year variable rate discounts held steady last week, and at this point my best guess is that the BoC will hike by another 0.50% when it next meets on October 27.

We live in interesting times (whether we like it or not).