Five Thoughts on the Bank of Canada’s Rate Hike

March 7, 2022Why Mortgage-Rate Rises Are About to Pack More Punch

March 21, 2022Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is first and foremost a tragic tale of human suffering, but it has also sent shockwaves through the global economy.

Oil, gas, and wheat prices have spiked by more than 30%, and many other commodity prices have surged higher. The price of nickel rose so fast that the London Metal Exchange had to temporarily suspend trading last week.

Companies lined up to announce that they were pulling out of Russia and writing off their investments there. A broad coalition of countries enacted the most draconian sanctions in history against Russia, and specifically targeted wealthy individuals in Russian President Vladimir Putin’s inner circle. Putin called these actions “economic war” and responded by announcing that he was putting his nuclear deterrent forces on high alert.

Fitch, a prominent bond rating agency, cut Russia’s credit rating to C and warned that its default is “imminent”. This raises financial contagion risks because it is estimated that international banks have approximately $121 billion in loans outstanding to Russian entities, with European banks most exposed.

While every country is feeling the impact of spiking energy prices, Europe is the most vulnerable to energy supply disruptions tied to the war. About 40% of the EU’s gas is imported from Russia and Putin has threatened to turn off the taps in response to the sanctions it has imposed (which thus far have not included Russian energy imports).

Other pockets of instability are also being tested and exposed by Russia’s war.

Unsurprisingly, investors have responded by moving into safe-haven assets, and that has caused the US dollar to appreciate against other currencies. When this happens, loans in emerging-market economies, which are tied to the US dollar, become more expensive, and that creates an additional economic headwind.

For example, a recent study by Bloomberg economists estimated that up to 30% of Chinese property-sector loans could default this year. Since many of that sector’s loans are tied to the US dollar, its default rate could be pushed even higher if the dollar appreciates materially against the Yuan.

In North America, spiking energy prices will drive the inflation rate higher just as pandemic-related supply bottlenecks are starting to clear. The question now is how the Bank of Canada (BoC) and the Fed will respond.

Central bankers tend to look through one-time price shocks, especially when they occur in typically volatile price categories like food and energy. But if the global economy shuts out Russia over the longer term (and whether that will happen isn’t clear at this point), they won’t be able to ignore the impact on prices.

Spiking food and energy prices are obviously inflationary over the short-term, but these fundamental commodities must still be consumed, regardless of their prices. As they become dearer, consumers have less to spend in other areas, and that demand destruction is deflationary.

In the past, oil price shocks have often led to recessions, and this time the shock will be coinciding with central-bank rate hikes.

The risk is rising that we will end up with elevated inflation alongside stagnant economic activity, a phenomenon referred to as stagflation. And at this point, at least until the fate of Ukraine becomes clearer, that is starting to look like the most likely outcome. The Bottom Line: Government of Canada bond yields initially plunged in response to Russia’s attack on Ukraine as investors piled into safe-haven assets. But those yields have since risen all the way back to their recent highs as inflation concerns have returned to the fore.

The Bottom Line: Government of Canada bond yields initially plunged in response to Russia’s attack on Ukraine as investors piled into safe-haven assets. But those yields have since risen all the way back to their recent highs as inflation concerns have returned to the fore.

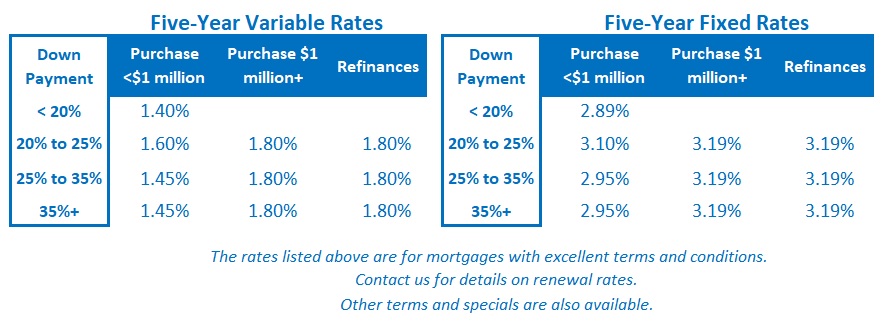

At the same time, risk premiums are being added to institutional borrowing rates. That has raised lender funding costs and, consequentially, our mortgage rates.

Both fixed and variable mortgage rates rose again last week, and the mix of recent events implies they will maintain that upward momentum over the near term.