US Inflation Falls in April (Sort of)

May 16, 2022What Is Happening with Inflation and Mortgage Rates?

May 30, 2022The Bank of Canada (BoC) has faced plenty of criticism of late.

It has a mandate to “maintain low, stable inflation over time”, and with prices spiking to their highest levels in more than 30 years, today’s inflation is more aptly described as “high and volatile”.

In retrospect, when our federal government responded to COVID with massive levels of stimulus spending, the Bank should have tightened monetary policy sooner than it did to help keep demand, and inflation, in check. But what is now clear in hindsight was less so during an economic shock that had policy makers focused, first and foremost, on avoiding a repeat of the Great Depression.

Also, to be fair, things would almost certainly have turned out quite differently if Russia hadn’t invaded Ukraine. That invasion caused additional spikes in food and energy prices on top of the pandemic-related inflation surge, which had been primarily caused by supply-chain bottlenecks and shortages tied to lockdowns.

But here we are, and the question, or, more appropriately, the dilemma, is how the BoC should proceed from here. Last month’s Canadian inflation data didn’t make things any easier.

It was hoped that the drop in US inflation, from 8.5% in March to 8.3% in April, might presage a similar easing of price pressures here at home. But that didn’t materialize. Instead, the Canadian inflation rate increased from 6.7% in March to 6.8% in April on an annualized basis.

Inflation is now broadening out and is harder to avoid, as noted by Globe and Mail reporter Matt Lundy, who observed that “about 70 per cent of the products and services that make up the Consumer Price Index (CPI) – the country’s main gauge of inflation – are rising by more than 3 per cent annually”.

Today’s elevated inflation might not even be the BoC’s most pressing concern, as a closer look at the current backdrop reveals (using some helpful charts courtesy of Ben Rabidoux, founder of Edge Realty Analytics).

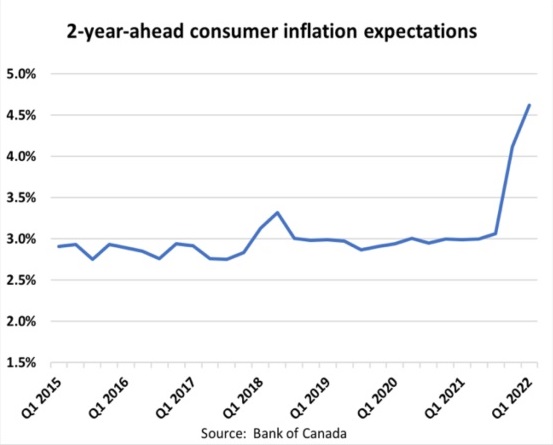

The first chart (right) shows what has happened to consumer inflation expectations quite recently.

The first chart (right) shows what has happened to consumer inflation expectations quite recently.

While the Bank still expects the causes of today’s inflationary pressures to prove transitory, that word has been banished to the history books. The term “transitory” is defined as “non-permanent”, which today’s inflation is likely to be, but in the context of the pandemic, the term also came to mean short-lived, and that has proven not to be the case.

Stickier-than-expected inflation has dealt a significant blow to the BoC’s credibility at a critical time, and the Bank’s most immediate concern is likely that consumer inflation expectations are becoming unanchored.

When that happens, consumers accelerate their purchase plans to avoid having to pay higher prices in future, and this increases short-term demand, further stoking inflationary pressures. At the same time, if workers believe that prices will continue to rise, they understandably demand higher wages to compensate for their lost purchasing power – and those higher wages push inflation higher still in a self-reinforcing cycle referred to as a “wage/price spiral”.

But if hiking rates seems like a simple solution, it’s not.

The BoC’s rate hikes can’t rein in the main causes of today’s inflationary pressures because they won’t end the conflict in Ukraine, lockdowns in China, droughts, or avian flu outbreaks. That makes them a blunt tool for the delicate job at hand.

In a recent publication, CIBC Chief economist Avery Shenfeld noted that the cyclical components of our economy, which will be most impacted by rate hikes, only represent about 20% of our current inflation rate. Based on that, he concludes that “even if the Bank had hiked earlier and managed to get cyclical inflation down to zero today, total inflation would still be around 5.5%.”

Shenfeld goes on to note, however, that shelter costs, which are classified as non-cyclical and are typically less likely to be impacted by rate hikes, may respond differently this time around because they are tied to “tightness in the residential construction sector” and, as such, are linked to its elevated material and labour costs. He expects the housing market “to cool rapidly” in response to rate hikes and concludes that “the Bank should therefore have more power than normal to affect the shelter component of inflation.”

That last point helps to lay bare the ultimate trade off the BoC will likely face between price stability and the health of our housing markets.

If the cyclical components that will be directly impacted by rate hikes aren’t causing enough of today’s inflation to make much of a difference, and if soaring food and energy prices are largely beyond the BoC’s control, then anchoring consumer expectations will likely come down to whether rate hikes can cool our housing markets.

This will be a fine line for the Bank to walk.

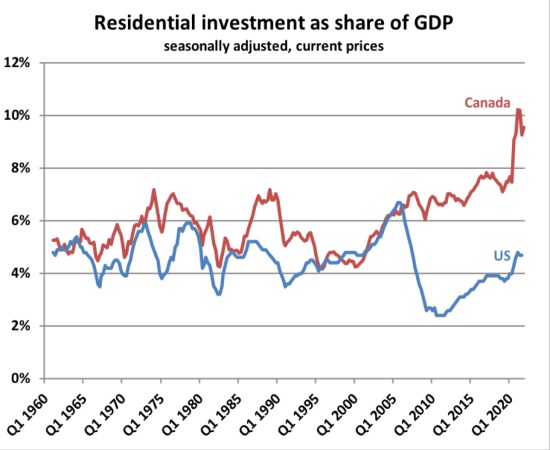

Our economic growth has been disproportionately underpinned by residential investment since the Great Recession in 2008 (see Rabidoux chart). The Bank has spent most of that time hoping (and forecasting) that exports and business investment will become the primary drivers of our economic momentum, but time and time again, residential investment fueled by cheap borrowing rates has usurped that role.

Our economic growth has been disproportionately underpinned by residential investment since the Great Recession in 2008 (see Rabidoux chart). The Bank has spent most of that time hoping (and forecasting) that exports and business investment will become the primary drivers of our economic momentum, but time and time again, residential investment fueled by cheap borrowing rates has usurped that role.

The resulting record-high levels of accumulated household debt now leave borrowers increasingly vulnerable to sharply higher rates and will magnify the impact of each BoC rate hike.

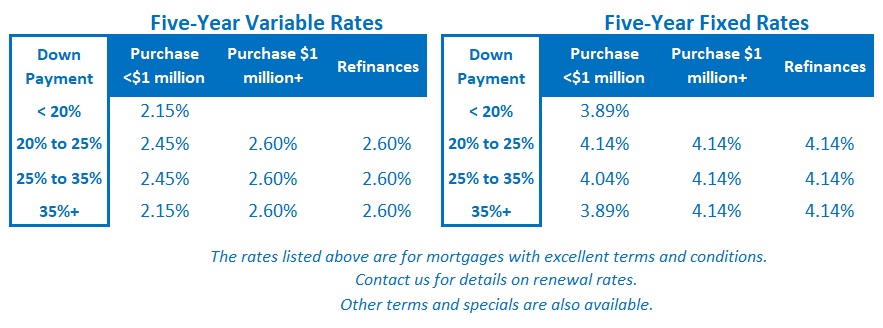

Now let’s go to the key question for readers of this post: What does this mean for fixed and variable mortgage rates going forward?

The five-year Government of Canada bond yield, which our fixed mortgage rates are based on, is currently pricing in about another 1.75% in BoC policy-rate hikes on top of the 0.75% we’ve seen thus far. But that still seems like an aggressive forecast to me.

Anyone choosing a fixed rate today is accepting the risk that they may be locking in at or near the peak but, importantly, they can mitigate some of that risk by ensuring that the penalties to break their mortgage contract early aren’t unfairly onerous. A reasonable prepayment penalty will allow you to benefit by refinancing if fixed rates drop back down over the medium term.

For my part, I think the BoC will be more cautious than the market predicts. In a recent speech, BoC Deputy Governor Toni Gravelle said that the Bank will be watching closely to see how our real-estate markets respond to BoC rate hikes, and he acknowledged that “we could see a larger-than-expected slowdown due to higher indebtedness and unsustainably high housing prices.”

Further, in terms of its overall objective, if the BoC wants to slow the economy, other factors are providing plenty of help.

To cite some examples, the recent run-up in fixed mortgage rates is already the most dramatic we have seen in more than 40 years, spiking food and energy prices are crimping other spending, and the record levels of fiscal stimulus that turbo-charged our economy through the pandemic have now been cut back.

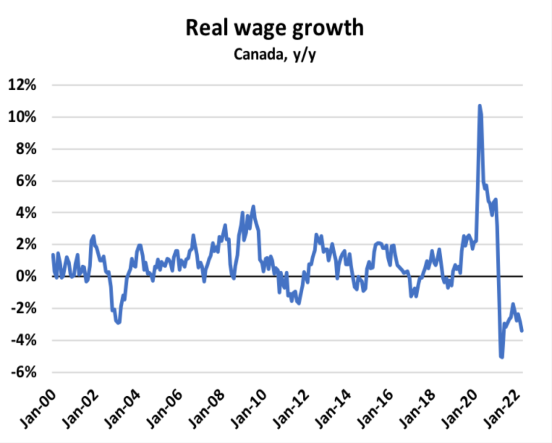

Most importantly, average wages have risen by only 3.3% over the past year, less than half our inflation rate over the same period. The resulting lower real incomes (see Rabidoux chart) mean that the average Canadian is losing purchasing power each month.

Most importantly, average wages have risen by only 3.3% over the past year, less than half our inflation rate over the same period. The resulting lower real incomes (see Rabidoux chart) mean that the average Canadian is losing purchasing power each month.

Against that backdrop, the excess savings on household balance sheets accumulated due to government support during the pandemic may not provide the “pre-loaded stimulus” that federal Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland has anticipated. Instead, our rapidly declining household saving rate implies that a good chunk of that excess cash is being used just to help Canadians keep their heads above water.

The BoC is widely expected to hike its policy rate by another 0.50% at its next meeting on June 1 and by another 0.50% at its following meeting on July 13. As those rate hikes compound, so too will the odds that our economic momentum will slow sharply at the expense of the cyclical components of our economy. Here’s hoping that inflation is now falling to a level where consumer expectations become once again firmly anchored – because I think rate rises beyond that point will stress our housing markets more than expected.

As you can probably surmise, I don’t think variable rates will peak much above 4%.

Instead, I think the many headwinds that are now buffeting our economy will combine with record-high household debt levels to slow our momentum by more than expected, and less monetary-policy tightening will be required as a result.

Furthermore, if the Bank hikes by more than expected, I think that will significantly increase the odds that a recession ensues and that rate cuts then follow.

(While it is possible that the BoC will continue to raise rates if inflation remains elevated, even as the economy materially weakens, that seems much less likely to me when the main causes are so clearly beyond its control.)

Fellow mortgage broker and Globe and Mail writer Rob McLister offered an astute statistical observation to support the view that sharply higher variable rates now portend lower variable rates in future.

He noted that “when the prime rate is more than 50-per-cent above its five-year moving average, variable rates historically cost less in the next five years than five-year fixed rates, well over nine times out of 10 [going back to 1945].” He added “The reason is simple: monetary policy works. Higher rates beget lower rates. That’s the beauty of rate cycles, and it’s why variables will ultimately be the only term of choice.”

The Bottom Line: Five-year fixed and variable rates continued to rise last week but not because of bond-yield rises or BoC rate hikes.

Rising risk premiums tied to elevated financial market volatility are increasing lender funding costs, and those increases are being passed on to borrowers in the form of higher rates. Those higher costs now appear to be already priced in, but the momentum indicator for both fixed and variable rates is still pointed up for the time being.

2 Comments

Hi Dave,

Long time reader, first time commenting.

I always hear the saying that what goes up must go down. Given the upward trajectory of mortgage rates and if the BoC does not hike the rates more than expected, will the rates remain as high as they are now or will we see a gradual decline?

Thankyou.

Hi Marlee,

The recent run-up in bond yields is based on the belief that the BoC (and the Fed) will hike rates repeatedly over the near term.

If those hikes don’t materialize to the extent expected, bond yields, and fixed mortgage rates, should fall from their current levels.

Best,

Dave