Are Changes to the Mortgage Stress Test Coming?

December 16, 2019The Bank of Canada’s Cautionary Comments Push Fixed Mortgage Rates Lower

January 27, 2020 In today’s post I offer my predictions of where our fixed and variable mortgage rates are headed in 2020. (For those who are interested, here is link to my 2019 forecast, which has aged fairly well.)

In today’s post I offer my predictions of where our fixed and variable mortgage rates are headed in 2020. (For those who are interested, here is link to my 2019 forecast, which has aged fairly well.)

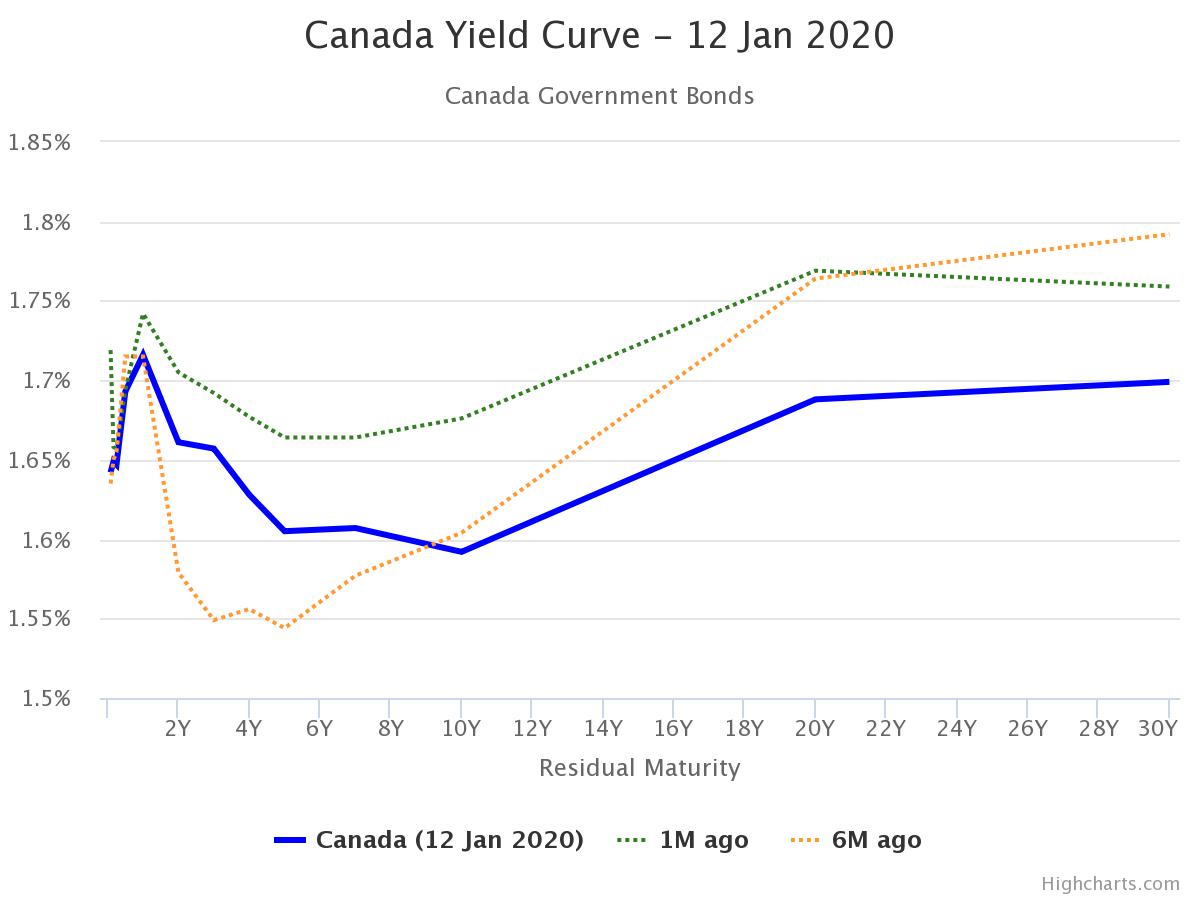

We begin 2020 with an unusual backdrop for mortgage rates. The Government of Canada (GoC) bond-yield curve, which our fixed mortgage rates are priced on, remains partially inverted.

As I explain in detail in this post, this is a phenomenon that doesn’t occur very often. In normal markets, longer term interest rates are higher than shorter term rates. A yield-curve inversion happens when the yields offered on longer-term bonds drop below the yields offered on shorter-term bonds (see chart).

In the current context, our yield curve is inverted essentially because the Bank of Canada (BoC) and the bond market have differing views on where our economy is headed.

At its last meeting of 2019, the Bank of Canada (BoC) continued to offer a relatively optimistic outlook for our growth prospects and determined that holding its policy rate steady at 1.75% was necessary in order to contain inflationary pressures. Conversely, the bond market spent 2019 bidding longer-term GoC bond yields lower, based on the belief that our economic growth will slow and that inflationary pressures will ease. (For anyone keeping score, the bond market has a much better forecasting track record than the BoC.)

Here are some examples of where their outlooks currently differ:

GDP Growth: In its most recent Monetary Policy Report (MPR), published in October, the BoC forecast that our GDP would grow by 1.3% quarter over quarter in Q4 of 2019. Since then we have learned that our GDP shrank by 0.1% in October on a month-over-month basis, and subsequent releases of the more detailed data that roll up into our GDP headline portend very little, if any, GDP growth in November and December. (Statistics Canada has yet to release its official GDP data for those months.)

Inflation: Overall inflation, as measured by our Consumer Price Index (CPI), rose to 2.2% in November, which the BoC attributed to the spike in year-over-year gas-price comparables that will roll off in the coming months. The Bank continues to forecast that overall inflation will trend toward its 2% target, but here again, the bond market doesn’t appear to agree.

GoC bond yields trended lower throughout most of 2019, and even our 30-year bond yield hovers at about 1.7%. If investors expected inflation to run at 2% in the medium and longer term, bond yields would be higher than that (especially given that the BoC hasn’t followed other central banks with quantitative easing measures designed to overwhelm market forces).

The bond market also appears to have it right over the short term.

The BoC has consistently forecast that our output gap, which measures the gap between our economy’s actual output and its maximum potential output, would close in the near future. (This is significant because inflationary pressures rise when the output gap closes.) But the bond market never took that bet, and data in the closing months of last year show that our output gap has begun to widen again. If that trend continues, inflationary pressures will ease.

Employment Strength: The BoC has highlighted the strength of our labour markets as an important factor in its optimistic outlook. Although 2019 did produce impressive job growth, the employment data stood in sharp contrast to most of our other economic indicators.

Our economy’s employment-growth momentum appeared to dissipate in November, when Statistics Canada estimated that we shed 71,000 jobs, marking our steepest monthly decline since the start of the Great Recession. Headline employment then rose by 35,000 new jobs in December, but some bounce back was expected, and the December details weren’t all positive. Both average wages and average hours worked fell, and the biggest gain was in accommodation and food service jobs, which are not considered to be of high quality.

Even if our employment growth continues to outpace most of our other economic indicators, it isn’t likely to stoke inflationary pressures. We added an estimated 320,000 new jobs in 2019, which was our best year for employment growth in more than a decade and that might have put upward pressure labour costs, but we also welcomed a record number of new immigrants over the same period and their total easily exceeded the new jobs number. (In the third quarter of 2019 alone, we added 185,000 new immigrants and non-permanent residents. Stats Can reported that this was our largest quarterly increase ever.)

The U.S. Economic Outlook: In its latest MPR, the BoC predicted that the U.S. economy will grow at “about potential” in 2020, which it forecast would be about 1.9%. Since then, U.S. consumer spending, which accounts for about 70% of total U.S. GDP, has slowed sharply. U.S. manufacturers and exporters remain mired in a deep slump, and with the U.S. federal budget deficit already at eye-watering levels, there is little room for additional stimulus to combat slowing momentum.

Equity-market optimists point to Phase One of the U.S./China trade deal as a sign that the trade uncertainty hanging over the U.S. economy might soon lift. Conversely, bond-market cynics (myself among them) would point out that even after Phase One is completed, the average U.S. tariff on Chinese goods will be 16% (compared to 3% before the trade war started), that Phase 2 will have to grapple with far more contentious items (like intellectual property rights), and that U.S. President Donald Trump sounds keen to turn his tariff guns on Europe as soon as the U.S./China trade war is resolved.

I think trade uncertainty will remain with us throughout 2020.

While sovereign bond yields move primarily in response to country-specific factors, international forces also influence their direction. For example, an economically destabilizing event or geopolitical crisis elsewhere can trigger a flight to safety where investors pile into safe-haven assets like sovereign bonds, and in so doing, drive down their yields.

Here are some examples of unfolding geopolitical events that could impact bond yields in 2020:

- Brexit – UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson is determined to make Brexit happen, but at what cost to the UK, to Europe and to the entire global financial system?

- The U.S./Iran conflict – Tensions have flared, and the risk of a significant escalation is rising.

- The dispute between India and Pakistan over Jammu and Kashmir – Tensions between two of the world’s nuclear powers could grab the world’s attention in a hurry.

- China and the Hong Kong protests – A heavy-handed response by China could have a significant impact on its trade relationships.

- The U.S. federal election and the impeachment of U.S. President Trump – U.S. political institutions will be put to the test in 2020, and the U.S. electorate is deeply divided.

Any of the above events could cause a panic in financial markets that would drive sovereign bond yields lower, but none more so than the elephant in any room where mortgage rate forecasts are being discussed: debt.

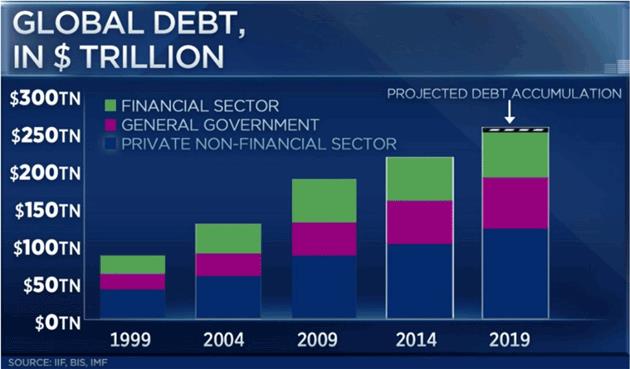

Global debt surpassed $250 trillion at the end of 2019. The chart below captures its breathtaking rise since the turn of the century (chart courtesy of CNBC by way of John Mauldin):

This sharp rise in debt has occurred across every sector of the global economy (government, consumer, corporate) and in developed and developing countries alike. Most concerningly, since the start of the Great Recession, global debt has risen five times faster than global GDP.

Debt can be described simply as future demand brought forward. After years of excess borrowing, how much future demand is there left to take? This is why output gaps are rising and inflationary pressures are falling almost everywhere.

Debt also acts like an invasive garden weed that chokes off growth by soaking up capital that might otherwise help the healthiest parts of an economy grow. That’s why more than 50 central banks across the globe cut a total of 2,500 basis points off of their policy rates in 2019, which should go down in history as the Year of the Rate Cut.

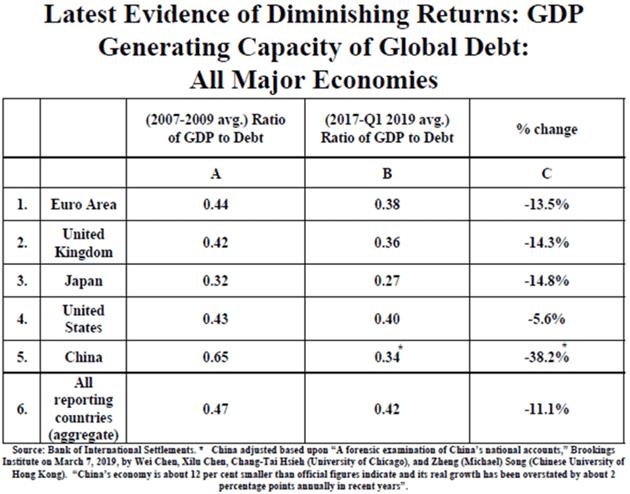

Worse still, the more debt an economy has, the less stimulative impact each newly borrowed dollar produces. This chart from a recent John Mauldin newsletter shows how debt’s impact on GDP has shrunk in each of the world’s largest economies over the past ten years: The temptation to borrow isn’t going away, but we have now most definitely entered the too-much-of-a-good-thing phase. And bluntly put, the more debt that gets added to the financial system, the greater the risk that we could see a black swan debt-default event that sends rates into the stratosphere.

The temptation to borrow isn’t going away, but we have now most definitely entered the too-much-of-a-good-thing phase. And bluntly put, the more debt that gets added to the financial system, the greater the risk that we could see a black swan debt-default event that sends rates into the stratosphere.

I’m not predicting we will see this in 2020, but any honest market watcher has to acknowledge that debt-associated tail risks are rising. (I will be writing about this more in future posts.)

So, what does all of this mean for Canadian mortgage borrowers?

Fixed Mortgage Rate Forecast

The bond market is pricing in a low-growth, low-inflation environment for the Canadian economy.

If GDP growth or inflation comes in higher than expected, elevated debt levels across every sector of our economy will magnify the negative impacts of even a small uptick in interest rates, making any sustainable rate rise unlikely.

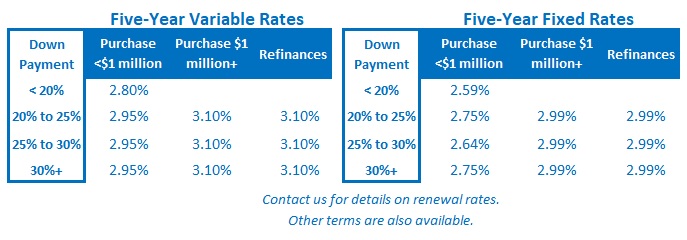

Our yield curve will stay inverted for as long as the bond market and the BoC don’t see eye to eye, and I don’t anticipate that changing any time soon. That means that five-year fixed rates are likely to be lower than shorter term fixed rates in the year ahead. (Seven- and ten-year fixed rates have higher associated funding costs, so these will likely remain higher than five-year fixed rates as well.)

I think five-year fixed rates will finish 2020 lower than they are now (barring a black swan event that I alluded to above) especially if geopolitical events trigger an investor flight to safety. If that happens, borrowers who have mortgage contracts with reasonable prepayment penalties will be able to take full advantage.

Variable Mortgage Ratee Forecast

The BoC was reluctant to lower its policy rate in 2019 for several reasons:

- Previous policy-rate cuts hadn’t stimulated the rise in business investment that the Bank had hoped for.

- The BoC’s current policy rate stands at 1.75%, and each incremental cut reduces its maneuverability in future, when rate cuts might then produce more of the desired impacts.

- The Bank’s previous rate cuts had mostly spurred a rise in already elevated consumer debt levels, which our policy makers are still trying to rein in. Also, consumer borrowing typically results in non-productive investment, which gives our economy only a short-term sugar high.

I think the BoC will remain reluctant to make additional rate cuts for the reasons outlined above, but at some point, it will have no choice.

With so many central banks cutting their policy rates, the Loonie has appreciated steadily against a basket of other currencies, and the Bank can’t ignore indefinitely the export-headwind that this produces. Also, I think that the U.S. economy will slow more than expected in 2020 and that the Fed will therefore continue cutting its policy rate over the next twelve months. If that happens, expect the BoC to follow in short order.

I think we will see at least one policy-rate cut from the BoC in 2020, and if I were a betting man, I’d have my money on two of them. That said, if the Bank does cut, five-year fixed rates are likely to drop as well. For that reason, I don’t expect variable rates to offer any material discount compared to fixed-rate alternatives. As such, I think variable mortgage rates will continue to have very limited appeal in the year ahead. (At the moment the futures market is only pricing in about a one-third chance of a 25-basis

point cut from the Bank of Canada in the first half of the year.) The Bottom Line: The GoC bond-yield curve remains inverted because the BoC and the bond market still don’t see eye to eye. For the reasons outlined above, I think the bond market’s indications of slower growth and lower inflation will prove correct in the year ahead.

The Bottom Line: The GoC bond-yield curve remains inverted because the BoC and the bond market still don’t see eye to eye. For the reasons outlined above, I think the bond market’s indications of slower growth and lower inflation will prove correct in the year ahead.

On a related note, I expect that our five-year fixed and variable rates will fall somewhat in 2020 and that both will finish the year lower than where they started (barring a black-swan-type credit event, which seems unlikely but should be noted as a rising risk).

If that forecast comes to fruition, five-year fixed rates will remain lower than five-year variable rates. For as long as that is the case, I expect that five-year fixed rates will continue to be the preferred option for the vast majority of borrowers.

1 Comment

Thanks!